History of French wine

The history of French wine, spans a period of at least 2600 years dating to the founding of Massalia in the 6th century BC by Phocaeans with the possibility that viticulture existed much earlier.

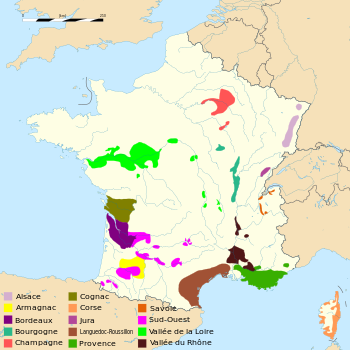

The Romans did much to spread viticulture across the land they knew as Gaul, encouraging the planting of vines in areas that would become the well known wine regions of Bordeaux, Burgundy, Alsace, Champagne, Languedoc, Loire Valley and the Rhone.

Prior to the French Revolution, the Catholic Church was one of France's largest vineyard owners-wielding considerable influence in regions such as Champagne and Burgundy where the concept of terroir first took root.

[2] A major turning-point in the wine history of Gaul came with the founding of Massalia in the 6th century BC by Greek immigrants from Phocaea in Asia Minor.

In 7 BC, the Greek geographer Strabo noted that the areas around Massilia and Narbo could produce the same fruits as Italy but the rest of Gaul further north could not support the olive, fig or vine.

Archaeological evidence dating to the reign of Augustus suggests that large numbers of amphorae were being produced near Bézier in the Narbonensis and in the Gaillac region of Southwest France.

[1] Expansion continued into the third century AD, pushing the borders of viticulture beyond the areas of the holm oak to places such as Bordeaux in Aquitania and Burgundy, where the more marginal climate included wet, cold summers that might not produce a harvest each year.

But even with the risk of an occasional lost harvest, the continuing demand for wine among the Roman and native inhabitants of Gaul made the proposition of viticulture a lucrative endeavor.

[1] The decline of the Roman Empire brought sweeping changes to Gaul, as the region was invaded by Germanic tribes from the north including the Visigoths, Burgundians and the Franks, none of whom were familiar with wine.

Port cities like Bordeaux, La Rochelle and Rouen emerged as formidable centers of commerce with the wines of Gascony, Haut Pays, Poitou and the Île-de-France.

When Petrarch wrote to Pope Urban V, pleading for his return to Rome, he noted that one obstacle to his request was that the best Burgundy wines could not be had south of the Alps.

[8] The 14th century was a period of peak prosperity for the Bordeaux-English wine trade that came to a close during the Hundred Years' War when Gascony came back under French control in 1453.

In 1756 the Academy of Bordeaux invited students to write papers on the topic of clarifying wines and the advantages or disadvantages of using egg whites as a fining agent.

Jean-Antoine Chaptal, the Minister of the Interior for Napoleon, felt that a contributing factor to this trend was the lack of knowledge among many French vignerons of the emerging technologies and winemaking practices that could improve the quality their wines.

It started in the 1850s with the introduction of powdery mildew, or oidium, which not only affected the skin color of the grapes but also reduced vine yields and the resulting quality of the wines.

However, while the importing of this new North American plant material helped to stave off the phylloxera epidemic, it brought with it yet more problems-the fungal disease of downy mildew that first surfaced in 1878 and black rot that followed in the 1880s.

During the 3 to 4 years that Pasteur spent studying wine he observed and explained the process of fermentation—noted that it was living organisms (yeast) that convert sugar in the grape must into alcohol in some form of chemical reaction.

Pasteur found that the particular problem of Burgundy wine spoiling and turning into vinegar on long voyages to England was caused by the bacterium acetobacter.

Programs have been enacted, in conjunction with the European Union, to combat the "wine lake" surplus problem by uprooting less desirable grape varieties and ensuring that vignerons receive technical training in viticulture and winemaking.

Three of the more prominent and pervasive influences came from the English/British people through both commercial interest and political factors, the Dutch who were significant players in the wine trade for much of the 16 and 17th century and the Catholic Church which held considerable vineyard properties until the French Revolution.

With a cool wet climate, the British Isles have historically produced dramatically different styles of wines than the French and in quantities too small to satisfy the London market.

The 1152 marriage between Eleanor of Aquitaine and the future King Henry II of England brought a large portion of southwest France under English rule.

When Henry's son John inherited the English crown, he sought to curry favor among the Gascons by bestowing upon them many privileges-the most notable of which was an exemption among Bordeaux merchants from the Grand Coutume export tax.

[9] For over the next 300 years much of Gascony, particular Bordeaux, benefited by the close commercial ties with the English allowing this area to grow in prominence among all French wines.

When political conflicts between the French and English flared up, it was the Dutch who stepped in to fill the void and serve as a continuing link funneling the wines of Bordeaux and La Rochelle into England.

By the end of the 17th century, with the aid of the Dutch, the future First Growth estates of Chateau Lafite, Latour and Margaux were planted and already starting to get notice abroad.

[17] The Merovingian period of Frankish rule saw the early seeds of monastic influence on French wine when Guntram, Clovis' grandson, gave a vineyard to the abbey of St. Benignus at Dijon.

The spread of viticulture during Charlemagne's reign was fueled in part by the expansion of the Christian Church which needed a daily supply of wine for the sacrament of the Eucharist, the monks' personal consumption as well as for hospitality extended to guests.

In the Loire Valley, the Benedictine monasteries in Bourgueil and La Charité extensively cultivated the lands around them while the abbey of St-Nicolas included large vineyards around Anjou.

[19] Through their extensive holdings, the monasteries of the Christian Church made many advances in French winemaking and viticulture with the study and observation of key vineyards sites, identifying the grape varieties that grew best in certain regions and discovering new methods of production.