Interlingue

Patre nor, qui es in li cieles, mey tui nómine esser sanctificat... Interlingue ([interˈliŋɡwe] ⓘ; ISO 639 ie, ile), originally Occidental ([oktsidenˈtaːl] ⓘ), is an international auxiliary language created in 1922 and renamed in 1949.

Readability and simplified grammar, along with the regular appearance of the magazine Cosmoglotta, made Occidental popular in Europe during the years before World War II despite efforts by the Nazis to suppress international auxiliary languages.

A Baltic German naval officer and teacher from Estonia, de Wahl refused to leave his Tallinn home for Germany, even after his house was destroyed in the 1943 air raids on the city forcing him to take refuge in a psychiatric hospital.

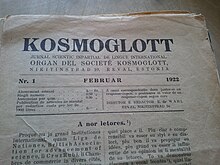

Edgar de Wahl announced the creation of Occidental in 1922 with the first issue of the magazine Cosmoglotta, published in Tallinn, Estonia under the name Kosmoglott.

The name was changed to Cosmoglotta in 1927 as it began to officially promote Occidental in lieu of other languages, and that January the magazine's editorial and administrative office was moved to the Vienna neighborhood of Mauer, now part of Liesing.

Originally entitled Cosmoglotta-Informationes,[23] it was soon renamed Cosmoglotta B, focusing on items of more internal interest such as linguistic issues, reports of Occidental in the news, and financial updates.

[34][35] Unaware of this, de Wahl was bewildered at the lack of response to his continued letters; even a large collection of poetry translated into Occidental was never delivered.

The other centres of Occidental activity in Europe did not fare as well, with the stocks of study materials in Vienna and Tallinn having been destroyed in bombings[45] and numerous Occidentalists sent to concentration camps in Germany and Czechoslovakia.

[66] Berger also feared that it might simply "disperse the partisans of the natural language with nothing to show for it" after Occidental had created "unity in the naturalistic school" for so long.

Interlingua also allowed optional irregular verbal conjugations such as so, son and sia as the first-person singular, third-person plural and subjunctive form of esser, the verb 'to be'.

[71][72] The magazine was financially strained by inflated postwar printing costs and its inability to collect payments from certain countries,[73] a marked contrast to the well-funded[74] New York-based IALA.

The beginning of the Cold War created an uncomfortable situation for the Occidental-Union,[76][77][78] whose name unfortunately coincided with that of an anti-Russian political league; the Swiss Occidentalists believed that was why all of de Wahl's letters from Tallinn were intercepted.

Vĕra Barandovská-Frank's perception of the situation at the time was as follows (translated from Esperanto): In the field of naturalistic planned languages Occidental-Interlingue was until then unchallenged (especially after the death of Otto Jespersen, author of Novial), as all new projects were nearly imitations of it.

This applied to Interlingua as well, but it carried with it a dictionary of 27 000 words put together by professional linguists that brought great respect, despite in principle only confirming the path that de Wahl had started.

In spite of attempts by diehard supporters of Occidental to stave off the inevitable — for instance, by such tactics as renaming their language Interlingue — most remaining Occidentalists made the short pilgrimage to the shrine of Interlingua.

Many subsequently moved to IALA's Interlingua, which however did not prove to be much more successful despite the impression its scientific origin made, and those who remained loyal to Occidental-Interlingue did not succeed in imparting their enthusiasm to a new generation.

[91] One example is The Esperanto Book released in 1995 by Harlow, who wrote that Occidental had an intentional emphasis on European forms and that some of its leading followers espoused a Eurocentric philosophy, which may have hindered its spread.

De Wahl later became one of the earliest users of Esperanto (la lingvo internacia), which he encountered for the first time in 1888 during his period as a Volapükist and for which he was in the process of composing a dictionary of marine terms.

[108][109][110][111][112] Among those de Wahl worked with while developing Occidental were Waldemar Rosenberger (Idiom Neutral), Julius Lott (Mundolingue), and Antoni Grabowski (Modern Latin for a time, before returning to Esperanto).

For example, just those used to form nouns referring to a type of person are as follows: -er- (molinero – miller), -or- (redactor – editor), -ari- (millionario – millionaire), -on- (spion, spy), -ard (mentard, liar), -astr- (poetastro, lousy poet), -es (franceso, Frenchman), -essa (reyessa, queen).

[121] De Wahl believed that the number of speakers did not always need to be taken into account, particularly in specialized areas such as botany where for example the term Oenethera biennis (a type of plant) should be implemented unchanged in an international language even if the entire world population of botanists, those most often familiar with and likely to use the word, did not exceed 10,000.

He cited the terms karma, ko-tau (kowtow), geisha, and mahdí in 1924 as examples of those that should not be put in a "vocalic corset"[95] through obligatory endings (e.g. karmo, koŭtoŭo, gejŝo, madho in Esperanto) when imported into the international language: Such words, still not large in number, have seen a large increase in the past century, and in the future will grow in exorbitant proportion when, through international communication, the ideas of stable Oriental cultures will inundate and influence the sick Europe, which is now losing its equilibrium.

[95]In an article on the future development of language, de Wahl wrote in 1927 that due to European dominance in the sciences and other areas Occidental required a form and derivation recognizable to Europeans, but that it should also be fitted with a grammatical structure capable of taking on more analytical, non-derived forms in the future (such as the equivalents of "bake man" for baker or "wise way" for wisdom) if worldwide linguistic trends began to show a preference for them.

"[131] De Wahl stressed that Occidental's natural appearance did not imply wholesale importation of national expressions and usage, and warned that doing so would lead to chaos.

[133] Occidental's erring on the side of regularity led to vocabulary that was still recognizable but different from the international norm, such as ínpossibil in place of impossibil (ín + poss + ibil), scientic (scientific, from scient-ie + -ic), and descrition (description, from descri-r + -tion).

This is one of the greatest differences between it and Interlingua, which has a vocabulary taken from so-called 'prototypes'[134] (the most recent common ancestor to its source languages) while Interlingue/Occidental focused on active, spontaneous derivation.

Those included Greek for science and philosophy (teorema, teosofie, astronomie), Latin for politics and law (social, republica, commission), Scandinavian, Dutch and English for navigation (log, fregatte, mast, brigg, bote), and various other international vocabulary originating in other languages (sabat, alcohol, sultan, divan, nirvana, orang-utan, bushido, té, dalai-lama, cigar, jazz, zebra, bumerang, etc.).

Beyond the five criteria, the Occidentalists at the time referenced the advantages of the lack of a fixed meaning for the tilde in the public sphere, and its similarity to a waveform, implying speech.

[140] Derived adverbs are formed by adding the suffix -men to an adjective (rapid = quick, rapidmen = quickly) Adjectives may be used as adverbs when the sense is clear:[140][156] Il ha bon laborat = He has worked well ("He has worked good") Noi serchat long = We looked for a long time ("We searched long") The application of de Wahl's rule to verbs, and the usage of numerous suffixes and prefixes, was created to resolve irregularities that had plagued creators of language projects before Occidental, who were forced to make the choice between regularity and unnatural forms, or irregularity and natural forms.

Some of the affixes used are:[152] As an international auxiliary language, ease of learning through regular derivation and recognizable vocabulary was a key principle in Occidental's creation.