History of Shaktism

"[10] Thousands of female statuettes dated as early as c. 5500 BCE have been recovered at Mehrgarh, one of the most important Neolithic sites in world archeology, and a precursor to the great Indus Valley civilization.

[11] In Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, major cities of the Indus valley civilization, female figurines were found in almost all households indicating the presence of cults of goddess worship.

It probably suggests an association between the female figure and crops, and possibly implies a ritual sacrifice where the blood of the victim was offered to the goddess for ensuring agricultural productivity.

[19] Other scholars like David Kinsley and Lynn Foulston acknowledge some similarities between the cult of goddess in Indus valley civilization and Shaktism, but think that there is no conclusive evidence that proves a link between them.

"[21]As these philosophies and rituals evolved in the northern reaches of the subcontinent, additional layers of Goddess-focused tradition were expanding outward from the sophisticated Dravidian civilizations of the south.

"[24] Indeed, Vedic descriptions of Aditi are vividly reflected in the countless so-called Lajja Gauri idols (depicting a faceless, lotus-headed goddess in birthing posture) that have been worshiped throughout India for millennia:[25] In the first age of the gods, existence was born from non-existence.

"[27] Also significant is the appearance, in the famous Rig Vedic hymn Devi Sukta, of two of Hinduism's most widely known and beloved goddesses: Vāc, identified with the present-day Saraswati; and Srī, now better known as Lakshmi.

It begins with the Vedic trinity of Agni, Vayu and Indra boasting and posturing in the flush of a recent victory over a demon hoard – until they suddenly find themselves bereft of divine power in the presence of a mysterious yaksha, or forest spirit.

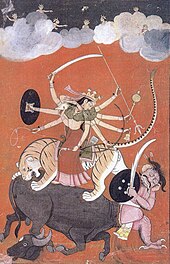

"[33] However, it is in the Epic's Durga Stotras[34] that "the Devi is first revealed in her true character, [comprising] numerous local goddesses combined into one [...] all-powerful Female Principle.

"[35] Meanwhile, the great Tamil epic, Silappatikaram[36] (c. 100 CE) was one of several literary masterpieces amply indicating "the currency of the cult of the Female Principle in South India" during this period – and, once again, "the idea that Lakshmi, Saraswati, Parvati, etc., represent different aspects of the same power.

"[37] Taken together with the Epics, the vast body of religious and cultural compilations known as the Puranas (most of which were composed during the Gupta period, c. 300 - 600 CE) "afford us greater insight into all aspects and phases of Hinduism – its mythology, its worship, its theism and pantheism, its love of God, its philosophy and superstitions, its festivals and ceremonies and ethics – than any other works.

'"[3] As the earliest Hindu scripture "in which the object of worship is conceptualized as Goddess, with a capital G",[41] the Devi Mahatmya also marks the birth of "independent Shaktism"; i.e. the cult of the Female Principle as a distinct philosophical and denominational entity.

The text is closely associated with another section of the Brahmanda Purana entitled Lalitopakhyana ("The Great Narrative of Lalita"), which extols the deeds of the Goddess in her form as Lalita-Tripurasundari, in particular her slaying of the demon Bhandasura.

[4] The text operates on a number of levels, containing references not just to the Devi's physical qualities and exploits but also an encoded guide to philosophy and esoteric practices of kundalini yoga and Srividya Shaktism.

In addition, many southern temples included shrines to the Sapta Matrika and "from the earliest period the South had a rich tradition of the cult of the village mothers, concerned with the facts of daily life.

[49] Dasgupta speculates that the Tantric image of a wild Kali standing on a slumbering Shiva was inspired from the Samkhyan conception of Prakriti as a dynamic agent and Purusha as a passive witness.

Around 800 CE, Adi Shankara, the legendary sage and preceptor of the Advaita Vedanta system, implicitly recognized Shakta philosophy and Tantric liturgy as part of mainstream Hinduism in his powerful (and still hugely popular) hymn known as Saundaryalahari or "Waves of Beauty".

"[6] Another important Shakta text often attributed to Shankara is the Mahishasura Mardini Stotra, a 21-verse hymn derived from the Devi Mahatmya that constitutes "one of the greatest works ever addressed to the supreme feminine power.

From the fourteenth century onward, "the Shakta-Tantric cults had [...] become woven into the texture of all the religious practices current in India," their spirit and substance infusing regional and sectarian vernacular as well as Sanskrit literature.

Works of the prolific and erudite Bhaskararaya, the most "outstanding contributor to Shakta philosophy," also belong to this period and remain central to Srividya practice even today.

[54] The great Tamil composer Muthuswami Dikshitar (1775–1835), a Srividya adept, set one of that tradition's central mysteries – the majestic Navavarana Puja – to music in a Caranatic classical song cycle known as the Kamalamba Navavarna Kritis.

"[55] In the meantime an even greater wave of popular Shaktism was swelling in eastern India with the passionate Shakta bhakti lyrics of two Bengali-language court poets—Bharatchandra Ray (1712–1760) and Ramprasad Sen (1718/20–1781)—which "opened not only a new horizon of the Shakti cult but made it acceptable to all, irrespective of caste or creed."

"[58][57] Another major advocate of Shaktism in this period was Sir John Woodroffe (1865–1936), a High Court judge in British India and "the father of modern Tantric studies," whose vast oeuvre "bends over backward to defend the Tantras against their many critics and to prove that they represent a noble, pure, ethical system in basic accord with the Vedas and Vedanta."

Another of India's great nationalists, Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950), later reinterpreted "the doctrine of Shakti in a new light" by drawing on "the Tantric conception of transforming the mortal and material body into [something] pure and divine," and setting a goal of "complete and unconditional surrender to the will of the Mother.

[64] As her film brought her to life, Santoshi Ma quickly became one of the most important and widely worshiped goddesses in India, taking her place in poster-art form in the altar rooms of millions of Hindu homes.

"[8] While some of these teachers represent conservative and patriarchal lineages of mainstream Hinduism, Pechilis notes that others – for example Mata Amritanandamayi and Mother Meera – operate in a strongly "feminine mode" that is distinctly bhaktic and Shakta in nature.