History of polio

[2] The fear and the collective response to these epidemics would give rise to extraordinary public reaction and mobilization spurring the development of new methods to prevent and treat the disease and revolutionizing medical philanthropy.

Ancient Egyptian paintings and carvings depict otherwise healthy people with withered limbs, and children walking with canes at a young age.

A retrospective diagnosis of polio is considered to be strong due to the detailed account Scott later made,[9] and the resultant lameness of his right leg had an important effect on his life and writing.

[11] In 1789 the first clinical description of poliomyelitis was provided by the British physician Michael Underwood—he refers to polio as "a debility of the lower extremities".

[12] The first medical report on poliomyelitis was by Jakob Heine, in 1840; he called the disease Lähmungszustände der unteren Extremitäten ("Paralysis of the lower Extremities").

[14] Numerous epidemics of varying magnitude began to appear throughout the country; by 1907 approximately 2,500 cases of poliomyelitis were reported in New York City.

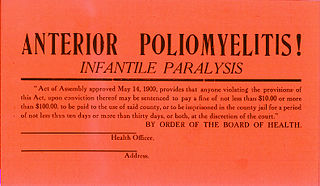

[17][18] The names and addresses of individuals with confirmed polio cases were published daily in the press, their houses were identified with placards, and their families were quarantined.

[19] Hiram M. Hiller, Jr. was one of the physicians in several cities who realized what they were dealing with, but the nature of the disease remained largely a mystery.

The 1916 epidemic caused widespread panic and thousands fled the city to nearby mountain resorts; movie theaters were closed, meetings were canceled, public gatherings were almost nonexistent, and children were warned not to drink from water fountains, and told to avoid amusement parks, swimming pools, and beaches.

[22] Young children who contract polio generally develop only mild symptoms, but as a result they become permanently immune to the disease.

[1] In the United States, the 1952 polio epidemic was the worst outbreak in the nation's history, and is credited with heightening parents' fears of the disease and focusing public awareness on the need for a vaccine.

In John Haven Emerson's A Monograph on the Epidemic of Poliomyelitis (Infantile Paralysis) in New York City in 1916[28] one suggested remedy reads: Give oxygen through the lower extremities, by positive electricity.

Kola, dry muriate of quinine, elixir of cinchone, radium water, chloride of gold, liquor calcis and wine of pepsin.

[32][33] Patients with residual paralysis were treated with braces and taught to compensate for lost function with the help of calipers, crutches and wheelchairs.

The use of devices such as rigid braces and body casts, which tended to cause muscle atrophy due to the limited movement of the user, were also touted as effective treatments.

[35] The first iron lung used in the treatment of polio was invented by Philip Drinker, Louis Agassiz Shaw, and James Wilson at Harvard, and tested October 12, 1928, at Children's Hospital, Boston.

[36] The original Drinker iron lung was powered by an electric motor attached to two vacuum cleaners, and worked by changing the pressure inside the machine.

[6] In 1940, Sister Elizabeth Kenny, an Australian bush nurse from Queensland, arrived in North America and challenged this approach to treatment.

In treating polio cases in rural Australia between 1928 and 1940, Kenny had developed a form of physical therapy that—instead of immobilizing affected limbs—aimed to relieve pain and spasms in polio patients through the use of hot, moist packs to relieve muscle spasm and early activity and exercise to maximize the strength of unaffected muscle fibers and promote the neuroplastic recruitment of remaining nerve cells that had not been killed by the virus.

[49] During the late 1940s and early 1950s, a research group, headed by John Enders at the Boston Children's Hospital, successfully cultivated the poliovirus in human tissue.

In 1954, the vaccine was tested for its ability to prevent polio; its field trials grew to be the largest medical experiment in history.

[14] Eight years after Salk's success, Albert Sabin developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using live but weakened (attenuated) virus.

[14] The consequences of the disease left polio survivors marked for life, leaving behind vivid images of wheelchairs, crutches, leg braces, breathing devices, and deformed limbs.

However, polio changed not only the lives of those who survived it, but also affected profound cultural changes: the emergence of grassroots fund-raising campaigns that would revolutionize medical philanthropy, the rise of rehabilitation therapy and, through campaigns for the social and civil rights of disabled people, polio survivors helped to spur the modern disability rights movement.

Its hugely successful fund-raising campaigns collected hundreds of millions of dollars—more than all of the U.S. charities at the time combined (with the exception of the Red Cross).

[57] Prior to the polio scares of the twentieth century, most rehabilitation therapy was focused on treating injured soldiers returning from war.

The disabling effects of polio led to heightened awareness and public support of physical rehabilitation, and in response a number of rehabilitation centers specifically aimed at treating polio patients were opened, with the task of restoring and building their remaining strength and teaching new, compensatory skills to large numbers of newly paralyzed individuals.

[59] As thousands of polio survivors with varying degrees of paralysis left the rehabilitation hospitals and went home, to school and to work, many were frustrated by a lack of accessibility and discrimination they experienced in their communities.