History of botany

The history of botany examines the human effort to understand life on Earth by tracing the historical development of the discipline of botany—that part of natural science dealing with organisms traditionally treated as plants.

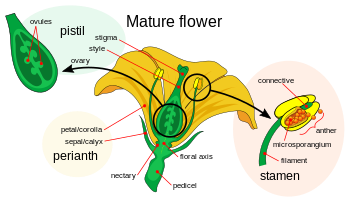

Early natural history divided pure botany into three main streams morphology-classification, anatomy and physiology – that is, external form, internal structure, and functional operation.

Nomadic hunter-gatherer societies passed on, by oral tradition, what they knew (their empirical observations) about the different kinds of plants that they used for food, shelter, poisons, medicines, for ceremonies and rituals etc.

[5] The nomadic life-style was drastically changed when settled communities were established in about twelve centres around the world during the Neolithic Revolution which extended from about 10,000 to 2500 years ago depending on the region.

With these communities came the development of the technology and skills needed for the domestication of plants and animals and the emergence of the written word provided evidence for the passing of systematic knowledge and culture from one generation to the next.

All of today's staple foods were domesticated in prehistoric times as a gradual process of selection of higher-yielding varieties took place, possibly unknowingly, over hundreds to thousands of years.

[11] Botanical historian Alan Morton notes that agriculture was the occupation of the poor and uneducated, while medicine was the realm of socially influential shamans, priests, apothecaries, magicians and physicians, who were more likely to record their knowledge for posterity.

[17] Together with Aristotle, he had tutored Alexander the Great whose military conquests were carried out with all the scientific resources of the day, the Lyceum garden probably containing many botanical trophies collected during his campaigns as well as other explorations in distant lands.

He noted that plants could be annuals, perennials and biennials, they were also either monocotyledons or dicotyledons and he also noticed the difference between determinate and indeterminate growth and details of floral structure including the degree of fusion of the petals, position of the ovary and more.

This work proved to be the definitive text on medicinal herbs, both oriental and occidental, for fifteen hundred years until the dawn of the European Renaissance being slavishly copied again and again throughout this period.

[27] Roman encyclopaedist Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) deals with plants in Books 12 to 26 of his 37-volume highly influential work Naturalis Historia in which he frequently quotes Theophrastus but with a lack of botanical insight although he does, nevertheless, draw a distinction between true botany on the one hand, and farming and medicine on the other.

These were free of superstition and myth with carefully researched descriptions and nomenclature; they included cultivation information and notes on economic and medicinal uses — and even elaborate monographs on ornamental plants.

[33][verification needed] [34] Important medieval Indian works of plant physiology include the Prthviniraparyam of Udayana, Nyayavindutika of Dharmottara, Saddarsana-samuccaya of Gunaratna, and Upaskara of Sankaramisra.

[42] However, it was Valerius Cordus (1515–1544) who pioneered the formal botanical description that detailed both flowers and fruits, some anatomy including the number of chambers in the ovary, and the type of ovule placentation.

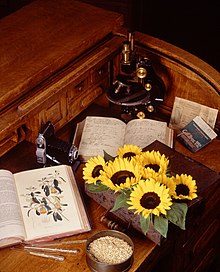

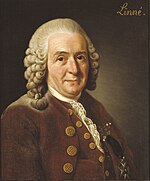

[47] The 18th century Enlightenment values of reason and science coupled with new voyages to distant lands instigating another phase of encyclopaedic plant identification, nomenclature, description and illustration, "flower painting" possibly at its best in this period of history.

[48][49] Plant trophies from distant lands decorated the gardens of Europe's powerful and wealthy in a period of enthusiasm for natural history, especially botany (a preoccupation sometimes referred to as "botanophilia") that is never likely to recur.

By the 18th century, the physic gardens had been transformed into "order beds" that demonstrated the classification systems that were being devised by botanists of the day — but they also had to accommodate the influx of curious, beautiful and new plants pouring in from voyages of exploration that were associated with European colonial expansion.

[68] The 17th century also marked the beginning of experimental botany and application of a rigorous scientific method, while improvements in the microscope launched the new discipline of plant anatomy whose foundations, laid by the careful observations of Englishman Nehemiah Grew[69] and Italian Marcello Malpighi, would last for 150 years.

Significant botanical collections came from: the West Indies (Hans Sloane (1660–1753)); China (James Cunningham); the spice islands of the East Indies (Moluccas, George Rumphius (1627–1702)); China and Mozambique (João de Loureiro (1717–1791)); West Africa (Michel Adanson (1727–1806)) who devised his own classification scheme and forwarded a crude theory of the mutability of species; Canada, Hebrides, Iceland, New Zealand by Captain James Cook's chief botanist Joseph Banks (1743–1820).

Jan Helmont (1577–1644) by experimental observation and calculation, noted that the increase in weight of a growing plant cannot be derived purely from the soil, and concluded it must relate to water uptake.

In his Vergleichende Untersuchungen of 1851, Wilhelm Hofmeister (1824–1877) starting with the ferns and bryophytes demonstrated that the process of sexual reproduction in plants entails an "alternation of generations" between sporophytes and gametophytes.

[91] This initiated the new field of comparative morphology which, largely through the combined work of William Farlow (1844–1919), Nathanael Pringsheim (1823–1894), Frederick Bower, Eduard Strasburger and others, established that an "alternation of generations" occurs throughout the plant kingdom.

This was followed by another grand synthesis, the Pflanzengeographie auf Physiologischer Grundlage of Andreas Schimper (1856–1901) in 1898 (published in English in 1903 as Plant-geography upon a physiological basis translated by W. R. Fischer, Oxford: Clarendon press, 839 pp).

With genetic continuity confirmed and the finding by Eduard Strasburger that the nuclei of reproductive cells (in pollen and embryo) have a reducing division (halving of chromosomes, now known as meiosis) the field of heredity was opened up.

[108] His theory probably stimulated the opposing views of German botanists Alexander Braun (1805–1877) and Matthias Schleiden who applied the experimental method to the principles of growth and form that were later extended by Augustin de Candolle (1778–1841).

The mechanism of photosynthesis remained a mystery until the mid-19th century when Sachs, in 1862, noted that starch was formed in green cells only in the presence of light, and in 1882, he confirmed carbohydrates as the starting point for all other organic compounds in plants.

In 1903, Chlorophylls a and b were separated by thin layer chromatography then, through the 1920s and 1930s, biochemists, notably Hans Krebs (1900–1981) and Carl (1896–1984) and Gerty Cori (1896–1957) began tracing out the central metabolic pathways of life.

Genetic engineering, the insertion of genes into a host cell for cloning, began in the 1970s with the invention of recombinant DNA techniques and its commercial applications applied to agricultural crops followed in the 1990s.

In the 1980s-90s, molecular analysis revealed an evolutionary divergence of fungi from other organisms about 1 billion years ago – sufficient reason to erect a unique kingdom separate from plants.

Building on the extensive earlier work of Alphonse de Candolle, Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943) from 1914 to 1940 produced accounts of the geography, centres of origin, and evolutionary history of economic plants.