Knot

Knot tying skills are often transmitted by sailors, scouts, climbers, canyoners, cavers, arborists, rescue professionals, stagehands, fishermen, linemen and surgeons.

Many knots can also be used as makeshift tools, for example, the bowline can be used as a rescue loop, and the munter hitch can be used for belaying.

In the event of someone falling into a ravine or a similar terrain feature, with the correct equipment and knowledge of knots a rappel system can be set up to lower a rescuer down to a casualty and set up a hauling system to allow a third individual to pull both the rescuer and the casualty out of the ravine.

Note the systems mentioned typically require carabiners and the use of multiple appropriate knots.

Knots can be applied in combination to produce complex objects such as lanyards and netting.

Macramé, one kind of textile, is generated exclusively through the use of knotting, instead of knits, crochets, weaves or felting.

Macramé can produce self-supporting three-dimensional textile structures, as well as flat work, and is often used ornamentally or decoratively.

The bending, crushing, and chafing forces that hold a knot in place also unevenly stress rope fibers and ultimately lead to a reduction in strength.

The exact mechanisms that cause the weakening and failure are complex and are the subject of continued study.

Special fibers that show differences in color in response to strain are being developed and used to study stress as it relates to types of knots.

Prudent users allow for a large safety margin in the strength of rope chosen for a task due to the weakening effects of knots, aging, damage, shock loading, etc.

The working load limit of a rope is generally specified with a significant safety factor, up to 15:1 for critical applications.

To capsize (or spill) a knot is to change its form and rearrange its parts, usually by pulling on specific ends in certain ways.

For example, loop knots share the attribute of having some kind of an anchor point constructed on the standing end (such as a loop or overhand knot) into which the working end is easily hitched, using a round turn.

[13] Other noted trick knots include: Coxcombing is a decorative knotwork performed by sailors during the Age of Sail.

The general purpose was to dress-up, protect, or help identify specific items and parts of ships and boats.

It is still found today in some whippings and wrappings of small diameter line on boat tillers and ships' wheels to enhance the grip, or to identify rudder amidships.

[15] A simple mathematical theory of hitches has been proposed by Bayman[16] and extended by Maddocks and Keller.

Nylon webbing, on the other hand, is flat, and usually "tubular" in construction, meaning that it is spiral-woven, and has a hollow core.

Tools are sometimes employed in the finishing or untying of a knot, such as a fid, a tapered piece of wood that is often used in splicing.

However, for cordage and other non-metallic appliances, the tools used are generally limited to sharp edges or blades such as a sheepsfoot blade, occasionally a fine needle for proper whipping of laid rope, a hot cutter for nylon and other synthetic fibers, and (for larger ropes) a shoe for smoothing out large knots by rolling them on the ground.

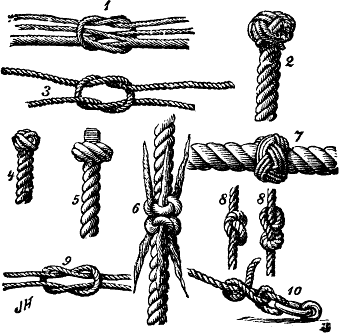

- Yarn knot ( ABoK #2688)

- Manrope knot ( ABoK #847)

- Granny knot ( ABoK #1206)

- Wall and crown knot ( ABoK #670, #671)

- Matthew Walker's knot ( ABoK #681)

- Shroud knot ( ABoK #1580)

- Turk's head knot ( ABoK #1278-#1397)

- Overhand knot , Figure-of-eight knot ( ABoK #514, #520)

- Reef knot , Square knot ( ABoK #1402)

- Two half-hitches ( ABoK #54)