History of macroeconomic thought

He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.

[2] Beginning with William Stanley Jevons and Clément Juglar in the 1860s,[8] economists attempted to explain the cycles of frequent, violent shifts in economic activity.

Most business cycle theories focused on a single factor,[9] such as monetary policy or the impact of weather on the largely agricultural economies of the time.

This was consistent with the classical dichotomy view that real aspects of the economy and nominal factors, such as price levels and money supply, can be considered independent from one another.

According to Wicksell, money would be created endogenously, without an increase in quantity of hard currency, as long as the natural exceeded the market interest rate .

[24] He explained the relationship via changing liquidity preferences:[25] people increase their money holdings during times of economic difficulty by reducing their spending, which further slows the economy.

[28] Classical economists had difficulty explaining involuntary unemployment and recessions because they applied Say's law to the labor market and expected that all those willing to work at the prevailing wage would be employed.

Since consumption remains stable, most fluctuations in aggregate demand stem from investment, which is driven by many factors including expectations, "animal spirits", and interest rates.

[33] Keynes thought strong public investment and fiscal policy would counter the negative impacts the uncertainty of economic fluctuations can have on the economy.

Economists and scholars debate whether Keynes intended his advice to be a major policy shift to address a serious problem or a moderately conservative solution to deal with a minor issue.

One group emerged representing the "orthodox" interpretation of Keynes; They combined classical microeconomics with Keynesian thought to produce the "neoclassical synthesis"[35] that dominated economics from the 1940s until the early 1970s.

[51] The IS/LM model focused on interest rates as the "monetary transmission mechanism," the channel through which money supply affects real variables like aggregate demand and employment.

Modigliani's model represented the economy as a system with general equilibrium across the interconnected markets for labor, finance, and goods,[47] and it explained unemployment with rigid nominal wages.

[53] Growth had been of interest to 18th-century classical economists like Adam Smith, but work tapered off during the 19th and early 20th century marginalist revolution when researchers focused on microeconomics.

[55] Economists incorporated the theoretical work from the synthesis into large-scale macroeconometric models that combined individual equations for factors such as consumption, investment, and money demand[61] with empirically observed data.

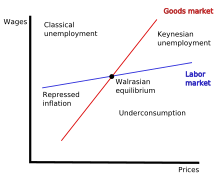

[80] Europeans such as Edmond Malinvaud and Jacques Drèze expanded on the disequilibrium tradition and worked to explain price rigidity instead of simply assuming it.

Eventually, firms will adjust their prices and wages for inflation based on real factors, ignoring nominal changes from monetary policy.

[85] Anna Schwartz collaborated with Friedman to produce one of monetarism's major works, A Monetary History of the United States (1963), which linked money supply to the business cycle.

[4] Monetarism became less credible when once-stable money velocity defied monetarist predictions and began to move erratically in the United States during the early 1980s.

[114] Thomas Sargent and Neil Wallace (1975)[n] applied rational expectations to models with Phillips curve trade-offs between inflation and output and found that monetary policy could not be used to systematically stabilize the economy.

Sargent and Wallace's policy ineffectiveness proposition found that economic agents would anticipate inflation and adjust to higher price levels before the influx of monetary stimulus could boost employment and output.

[118] Both Hall's and Friedman's versions of the permanent income hypothesis challenged the Keynesian view that short-term stabilization policies like tax cuts can stimulate the economy.

[140] These early new Keynesian theories were based on the basic idea that, given fixed nominal wages, a monetary authority (central bank) can control the employment rate.

[162] Olivier Blanchard and Lawrence Summers (1986)[x] explained hysteresis in unemployment with insider-outsider models, which were also proposed by Assar Lindbeck and Dennis Snower in a series of papers and then a book.

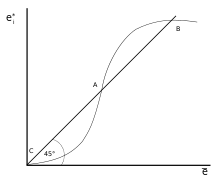

[179] This strain of research began with Mankiw, Romer, and Weil (1992),[ac] which showed that 78% of the cross-country variance in growth could be explained by a Solow model augmented with human capital.

A paper by Frank Smets and Rafael Woulters (2007)[ae] stated that monetary policy explained only a small part of the fluctuations in economic output.

[202] Whilst criticizing DSGE models, Ricardo J. Caballero argued that work in finance showed progress and suggested that modern macroeconomics needed to be re-centered but not scrapped in the wake of the financial crisis.

Using novel Bayesian estimation methods, Frank Smets and Raf Wouters[205] demonstrated that a sufficiently rich New Keynesian model could fit European data well.

Their finding, along with similar work by other economists, has led to widespread adoption of New Keynesian models for policy analysis and forecasting by central banks around the world.

Chari said in 2010 that the most advanced DSGE models allowed for significant heterogeneity in behavior and decisions, from factors such as age, prior experiences and available information.

Middle row: Solow , Friedman , Schwartz

Bottom row: Sargent , Fischer , Prescott