History of molecular biology

In its earliest manifestations, molecular biology—the name was coined by Warren Weaver of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1938[1]—was an idea of physical and chemical explanations of life, rather than a coherent discipline.

However, in the 1930s and 1940s it was by no means clear which—if any—cross-disciplinary research would bear fruit; work in colloid chemistry, biophysics and radiation biology, crystallography, and other emerging fields all seemed promising.

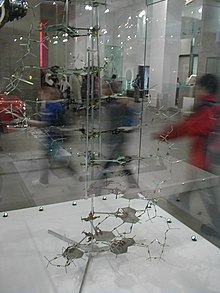

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the double helical structure of the DNA molecule based on the discoveries made by Rosalind Franklin.

Another fifteen years were required before new and more sophisticated technologies, united today under the name of genetic engineering, would permit the isolation and characterization of genes, in particular those of highly complex organisms.

Between the molecules studied by chemists and the tiny structures visible under the optical microscope, such as the cellular nucleus or the chromosomes, there was an obscure zone, "the world of the ignored dimensions," as it was called by the chemical-physicist Wolfgang Ostwald.

The successes of molecular biology derived from the exploration of that unknown world by means of the new technologies developed by chemists and physicists: X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy, ultracentrifugation, and electrophoresis.

The development of molecular biology is also the encounter of two disciplines which made considerable progress in the course of the first thirty years of the twentieth century: biochemistry and genetics.

[10] The phage group was an informal network of biologists that carried out basic research mainly on bacteriophage T4 and made numerous seminal contributions to microbial genetics and the origins of molecular biology in the mid-20th century.

But history decided differently: the arrival of the Nazis in 1933—and, to a less extreme degree, the rigidification of totalitarian measures in fascist Italy—caused the emigration of a large number of Jewish and non-Jewish scientists.

There remained the questions of how many strands came together, whether this number was the same for every helix, whether the bases pointed toward the helical axis or away, and ultimately what were the explicit angles and coordinates of all the bonds and atoms.

In an influential presentation in 1957, Crick laid out the "central dogma of molecular biology", which foretold the relationship between DNA, RNA, and proteins, and articulated the "sequence hypothesis."

In their seminal 1953 paper, Watson and Crick suggested that van der Waals crowding by the 2`OH group of ribose would preclude RNA from adopting a double helical structure identical to the model they proposed—what we now know as B-form DNA.

In 1955, Marianne Grunberg-Manago and colleagues published a paper describing the enzyme polynucleotide phosphorylase, which cleaved a phosphate group from nucleotide diphosphates to catalyze their polymerization.

These samples yielded the most readily interpretable fiber diffraction patterns yet obtained, suggesting an ordered, helical structure for cognate, double stranded RNA that differed from that observed in DNA.

[28] In 1971, Kim et al. achieved another breakthrough, producing crystals of yeast tRNAPHE that diffracted to 2–3 Ångström resolutions by using spermine, a naturally occurring polyamine, which bound to and stabilized the tRNA.

[29] Despite having suitable crystals, however, the structure of tRNAPHE was not immediately solved at high resolution; rather it took pioneering work in the use of heavy metal derivatives and a good deal more time to produce a high-quality density map of the entire molecule.

[30] This solution would be followed by many more, as various investigators worked to refine the structure and thereby more thoroughly elucidate the details of base pairing and stacking interactions, and validate the published architecture of the molecule.

[32] This unfortunate lack of scope would eventually be overcome largely because of two major advancements in nucleic acid research: the identification of ribozymes, and the ability to produce them via in vitro transcription.

In 1994, McKay et al. published the structure of a 'hammerhead RNA-DNA ribozyme-inhibitor complex' at 2.6 Ångström resolution, in which the autocatalytic activity of the ribozyme was disrupted via binding to a DNA substrate.

[36] The conformation of the ribozyme published in this paper was eventually shown to be one of several possible states, and although this particular sample was catalytically inactive, subsequent structures have revealed its active-state architecture.

With the advice of Jöns Jakob Berzelius, the Dutch chemist Gerhardus Johannes Mulder carried out elemental analyses of common animal and plant proteins.

The (correct) theory that proteins were linear polymers of amino acids linked by peptide bonds was proposed independently and simultaneously by Franz Hofmeister and Emil Fischer at the same conference in 1902.

Hence, early studies focused on proteins that could be purified in large quantities, e.g., those of blood, egg white, various toxins, and digestive/metabolic enzymes obtained from slaughterhouses.

In the late 1950s, the Armour Hot Dog Co. purified 1 kg (= one million milligrams) of pure bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A and made it available at low cost to scientists around the world.

In the mid-1920s, Tim Anson and Alfred Mirsky proposed that denaturation was a reversible process, a correct hypothesis that was initially lampooned by some scientists as "unboiling the egg".

In 1929, Hsien Wu hypothesized that denaturation was protein unfolding, a purely conformational change that resulted in the exposure of amino acid side chains to the solvent.

Although considered plausible, Wu's hypothesis was not immediately accepted, since so little was known of protein structure and enzymology and other factors could account for the changes in solubility, enzymatic activity and chemical reactivity.

Remarkably, Pauling's incorrect theory about H-bonds resulted in his correct models for the secondary structure elements of proteins, the alpha helix and the beta sheet.

The hydrophobic interaction was restored to its correct prominence by a famous article in 1959 by Walter Kauzmann on denaturation, based partly on work by Kaj Linderstrøm-Lang.

The ionic nature of proteins was demonstrated by Bjerrum, Weber and Arne Tiselius, but Linderstrom-Lang showed that the charges were generally accessible to solvent and not bound to each other (1949).