History of zoology (1859–present)

The end of the 19th century saw the fall of spontaneous generation and the rise of the germ theory of disease, though the mechanism of inheritance remained a mystery.

The 1859 publication of Darwin's theory in On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life is often considered the central event in the history of modern zoology.

However, natural selection would not be accepted as the primary mechanism of evolution until well into the 20th century, as most contemporary theories of heredity seemed incompatible with the inheritance of random variation.

[1][2][3] Alfred Russel Wallace, following on earlier work by de Candolle, Humboldt and Darwin, made major contributions to zoogeography.

Because of his interest in the transmutation hypothesis, he paid particular attention to the geographical distribution of closely allied species during his field work first in South America and then in the Malay Archipelago.

His method of tabulating data on animal groups in geographic zones highlighted the discontinuities; and his appreciation of evolution allowed him to propose rational explanations, which had not been done before.

Darwin's discoveries revolutionised the zoological and botanical sciences, by introducing the theory of evolution by natural selection as an explanation for the diversity of all animal and plant life.

[8] Almost a thousand years before Darwin, the Arab scholar Al-Jahiz (781–868) had already developed a rudimentary theory of natural selection , describing the Struggle for existence in his Book of Animals where he speculates on how environmental factors can affect the characteristics of species by forcing them to adapt and then passing on those new traits to future generations.

In consequence of this excess of births there is a struggle for existence and a survival of the fittest, and consequently an ever-present necessarily acting selection, which either maintains accurately the form of the species from generation to generation or leads to its modification in correspondence with changes in the surrounding circumstances which have relation to its fitness for success in the struggle for life, structures to the service of the organisms in which they occur.

of the transcendental morphologist, was seen to be nothing more than the expression of one of the laws of thremmatology, the persistence of hereditary transmission of ancestral characters, even when they have ceased to be significant or valuable in the struggle for existence, while the so-called evidences of design which was supposed to modify the limitations of types assigned to Himself by the Creator were seen to be adaptations due to the selection and intensification by selective breeding of fortuitous congenital variations, which happened to prove more useful than the many thousand other variations which did not survive in the struggle for existence.

[8] Thus not only did Darwin's theory give a new basis to the study of organic structure, but, while rendering the general theory of organic evolution equally acceptable and necessary, it explained the existence of low and simple forms of life as survivals of the earliest ancestry of the more highly complex forms, and revealed the classifications of the systematist as unconscious attempts to construct the genealogical tree or pedigree of plants and animals.

It abolished the conception of life as an entity above and beyond the common properties of matter, and led to the conviction that the marvellous and exceptional qualities of that which we call living matter are nothing more nor less than an exceptionally complicated development of those chemical and physical properties which we recognize in a gradually ascending scale of evolution in the carbon compounds, containing nitrogen as well as oxygen, sulphur and hydrogen as constituent atoms of their enormous molecules.

A more instructive subdivision must be one which corresponds to the separate currents of thought and mental preoccupation which have been historically manifested in western Europe in the gradual evolution of what is to-day the great river of zoological doctrine to which they have all been rendered contributory.

Scientists in the rising field of cytology, armed with increasingly powerful microscopes and new staining methods, soon found that even single cells were far more complex than the homogeneous fluid-filled chambers described by earlier microscopists.

[9][10] By the 1880s, bacteriology was becoming a coherent discipline, especially through the work of Robert Koch, who introduced methods for growing pure cultures on agar gels containing specific nutrients in Petri dishes.

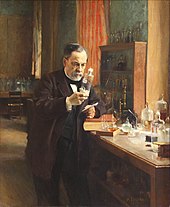

The long-held idea that living organisms could easily originate from nonliving matter (spontaneous generation) was attacked in a series of experiments carried out by Louis Pasteur, while debates over vitalism vs. mechanism (a perennial issue since the time of Aristotle and the Greek atomists) continued apace.

[11] Over the course of the 19th century, the scope of physiology expanded greatly, from a primarily medically oriented field to a wide-ranging investigation of the physical and chemical processes of life—including plants, animals, and even microorganisms in addition to man.

[12][13] Physiologists such as Claude Bernard explored (through vivisection and other experimental methods) the chemical and physical functions of living bodies to an unprecedented degree, laying the groundwork for endocrinology (a field that developed quickly after the discovery of the first hormone, secretin, in 1902), biomechanics, and the study of nutrition and digestion.

Much important work was done by Fritz Muller (Für Darwin), by Hermann Müller (Fertilization of Plants by Insects), August Weismann, Edward B. Poulton and Abbott Thayer.

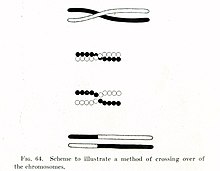

[8] At the beginning of the 20th century, the causes of congenital variation were obscure, although it was recognised that they were largely due to a mixing of the matter that constituted the fertilized germ or embryo-cell from two individuals.

Darwin, influenced by some facts that seemed to favour the Lamarckian hypothesis, thought that acquired characters are sometimes transmitted, but did not consider that this mechanism was likely to be of great importance.

Conversely, the vast number of experiments in the cropping of the tails and ears of domestic animals, as well as of similar operations on man, had negative results.

For example, the occurrence of blind animals in caves and in the deep sea was a fact that even Darwin regarded as best explained by the atrophy of the eye in successive generations through the absence of light and consequent disuse.

[8] It was argued that the elaborate structural adaptations of the nervous system that underlie instincts must have been slowly built up by the transmission to offspring of acquired experience.

It seemed hard to understand how complicated instincts could be due to the selection of congenital variations, or be explained except by the transmission of habits acquired by the parent.

[8] In the early 20th century, naturalists were faced with increasing pressure to add rigor and preferably experimentation to their methods, as the newly prominent laboratory-based biological disciplines had done.

[20] Charles Elton's studies of animal food chains was pioneering among the succession of quantitative methods that colonized the developing ecological specialties.

[24][25] Hugo de Vries tried to link the new genetics with evolution; building on his work with heredity and hybridization, he proposed a theory of mutationism, which was widely accepted in the early 20th century.

[28][29] In the 1970s Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge proposed the theory of punctuated equilibrium which holds that stasis is the most prominent feature of the fossil record, and that most evolutionary changes occur rapidly over relatively short periods of time.

[31] Also in the early 1980s, statistical analysis of the fossil record of marine organisms published by Jack Sepkoski and David M. Raup lead to a better appreciation of the importance of mass extinction events to the history of life on earth.