History of paleontology

[1] During the Middle Ages, fossils were discussed by Persian naturalist Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe) in The Book of Healing (1027), which proposed a theory of petrifying fluids that Albert of Saxony would elaborate on in the 14th century.

In early modern Europe, the systematic study of fossils emerged as an integral part of the changes in natural philosophy that occurred during the Age of Reason.

This contributed to a rapid increase in knowledge about the history of life on Earth, and progress towards definition of the geologic time scale largely based on fossil evidence.

[8] In 1027, the Persian naturalist Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe), proposed an explanation of how the stoniness of fossils was caused in The Book of Healing.

[9] Shen Kuo (Chinese: 沈括; 1031–1095) of the Song dynasty used marine fossils found in the Taihang Mountains to infer the existence of geological processes such as geomorphology and the shifting of seashores over time.

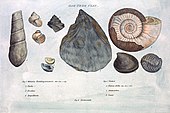

In folios 8 to 10 of the Leicester code, Leonardo examined the subject of body fossils, tackling one of the vexing issues of his contemporaries: why do we find petrified seashells on mountains?

[16] The interpretation of Leonardo da Vinci appears extraordinarily innovative as he surpassed three centuries of scientific debate on the nature of body fossils.

To da Vinci, ichnofossils played a central role in demonstrating: (1) the organic nature of petrified shells and (2) the sedimentary origin of the rock layers bearing fossil objects.

Da Vinci described what are bioerosion ichnofossils:[20] The hills around Parma and Piacenza show abundant mollusks and bored corals still attached to the rocks.

Leonardo used fossil burrows as paleoenvironmental tools to demonstrate the marine nature of sedimentary strata:[20]Between one layer and the other there remain traces of the worms that crept between them when they had not yet dried.

[23][24][25] For these reasons, Leonardo da Vinci is deservedly considered the founding father of both the major branches of palaeontology, i.e. the study of body fossils and ichnology.

[26] Hooke believed that fossils provided evidence about the history of life on Earth writing in 1668: ...if the finding of Coines, Medals, Urnes, and other Monuments of famous persons, or Towns, or Utensils, be admitted for unquestionable Proofs, that such Persons or things have, in former times had a being, certainly those Petrifactions may be allowed to be of equal Validity and Evidence, that there have formerly been such Vegetables or Animals... and are true universal Characters legible to all rational Men.

Steno who, like almost all 17th-century natural philosophers, believed that the earth was only a few thousand years old, resorted to the Biblical flood as a possible explanation for fossils of marine organisms that were far from the sea.

[29] In 1695 Ray wrote to the Welsh naturalist Edward Lluyd complaining of such views: "... there follows such a train of consequences, as seem to shock the Scripture-History of the novity of the World; at least they overthrow the opinion received, & not without good reason, among Divines and Philosophers, that since the first Creation there have been no species of Animals or Vegetables lost, no new ones produced.

In a pioneering application of stratigraphy, William Smith, a surveyor and mining engineer, made extensive use of fossils to help correlate rock strata in different locations.

He established the principle of faunal succession, the idea that each strata of sedimentary rock would contain particular types of fossils, and that these would succeed one another in a predictable way even in widely separated geologic formations.

Brongniart's work is the foundation of paleobotany and reinforced the theory that life on earth had a long and complex history, and different groups of plants and animals made their appearances in successive order.

Despite the skeletons being incomplete and the first being partially damaged from not being carefully collected by workers, he was able to determine based on postcranial evidence that A. commune was similar to animals that would eventually be classified in the order Artiodactyla after his lifetime.

That same year Gideon Mantell realized that some large teeth he had found in 1822, in Cretaceous rocks from Tilgate, belonged to a giant herbivorous land-dwelling reptile.

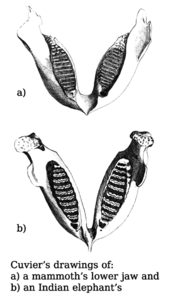

[55] In Cuvier's landmark 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he referred to a single catastrophe that destroyed life to be replaced by the current forms.

As a result of his studies of extinct mammals, he realized that animals such as Palaeotherium and Anoplotherium had lived before the time of the mammoths, which led him to write in terms of multiple geological catastrophes that had wiped out a series of successive faunas.

[57] In Great Britain, where natural theology was very influential in the early 19th century, a group of geologists that included Buckland, and Robert Jameson insisted on explicitly linking the most recent of Cuvier's catastrophes to the biblical flood.

[59] Lyell amassed evidence, both from his own field research and the work of others, that most geological features could be explained by the slow action of present-day forces, such as vulcanism, earthquakes, erosion, and sedimentation rather than past catastrophic events.

[64] Robert Chambers used fossil evidence in his 1844 popular science book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, which advocated an evolutionary origin for the cosmos as well as for life on earth.

In 1841, John Phillips formally divided the geologic column into three major eras, the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic, based on sharp breaks in the fossil record.

The relatively high level of public support for the earth sciences was due to their cultural impact, and their proven economic value in helping to exploit mineral resources such as coal.

[77] In 1861 the first specimen of Archaeopteryx, an animal with both teeth and feathers and a mix of other reptilian and avian features, was discovered in a limestone quarry in Bavaria and described by Richard Owen.

In particular some paleontologists such as Edward Drinker Cope and Henry Fairfield Osborn preferred alternatives such as neo-Lamarckism, the inheritance of characteristics acquired during life, and orthogenesis, an innate drive to change in a particular direction, to explain what they perceived as linear trends in evolution.

[85] Also in the early 1980s Jack Sepkoski and David M. Raup published papers with statistical analysis of the fossil record of marine invertebrates that revealed a pattern (possibly cyclical) of repeated mass extinctions with significant implications for the evolutionary history of life.

However, new analysis in the 1980s by Harry B. Whittington, Derek Briggs, Simon Conway Morris and others sparked a renewed interest and a burst of activity including discovery of an important new fossil site, Sirius Passet, in Greenland, and the publication of a popular and controversial book, Wonderful Life by Stephen Jay Gould in 1989.