History of money

[11] In the early 17th century Sweden lacked precious metals, and so produced "plate money": large slabs of copper 50 cm or more in length and width, stamped with indications of their value.

[15][16] The earliest ideas included Aristotle's "metallist" and Plato's "chartalist" concepts, which Joseph Schumpeter integrated into his own theory of money as forms of classification.

[31] The assignment of monetary value to an otherwise insignificant object such as a coin or promissory note arises as people acquired a psychological capacity to place trust in each other and in external authority within barter exchange.

His research indicates that gift economies were common, at least at the beginnings of the first agrarian societies, when humans used elaborate credit systems.

[35] Anthropologist Caroline Humphrey examines the available ethnographic data and concludes that "No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing".

[38] In a gift economy, valuable goods and services are regularly given without any explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e. there is no formal quid pro quo).

Instead, they are used to create, maintain, and otherwise reorganize relations between people: to arrange marriages, establish the paternity of children, head off feuds, console mourners at funerals, seek forgiveness in the case of crimes, negotiate treaties, acquire followers – almost anything but trade in yams, shovels, pigs, or jewelry.

In essence, to reduce complications and nuisance of trading and bartering, grain and silver were utilized by early civilizations because they were portable, had use, and were divisible.

The temple (which financed and controlled most foreign trade) fixed exchange rates between barley and silver, and other important commodities, which enabled payment using any of them.

[50][51] The Babylonians and their neighboring city states later developed the earliest system of economics as we think of it today, in terms of rules on debt,[41] legal contracts and law codes relating to business practices and private property.

All modern coins, in turn, are descended from the coins that appear to have been invented in the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor somewhere around 7th century BC and that spread throughout Greece in the following centuries: disk-shaped, made of gold, silver, bronze or imitations thereof, with both sides bearing an image produced by stamping; one side is often a human head.

[67] Other coins made of electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of silver and gold) were manufactured on a larger scale about 7th century BC in Lydia (on the coast of what is now Turkey).

The use and export of silver coinage, along with soldiers paid in coins, contributed to the Athenian Empire's dominance of the region in the 5th century BC.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the solidus continued to circulate for some time among the Franks; his name was kept and transformed into "sol" in French, then "sou".

[76] Charlemagne, in 800 AD, implemented a series of reforms upon becoming "Holy Roman Emperor", including the issuance of a standard coin, the silver penny.

[92] At around the same time in the medieval Islamic world, a vigorous monetary economy was created during the 7th–12th centuries on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar).

Ancient India was one of the earliest issuers of coins in the world,[96] along with the Lydian staters, several other Middle Eastern coinages and the Chinese wen.

In the 12th century, the English monarchy introduced an early version of the bill of exchange in the form of a notched piece of wood known as a tally stick.

The tallies could also be sold to other parties in exchange for gold or silver coin at a discount reflecting the length of time remaining until the tax was due for payment.

Since the promissory notes were payable on demand, and the advances (loans) to the goldsmith's customers were repayable over a longer time period, this was an early form of fractional reserve banking.

The promissory notes developed into an assignable instrument, which could circulate as a safe and convenient form of money backed by the goldsmith's promise to pay.

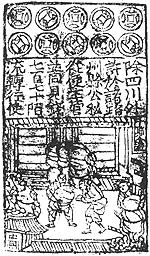

[106] These replaced the copper-plates being used instead as a means of payment,[107] although in 1664 the bank ran out of coins to redeem notes and ceased operating in the same year.

In the United States, this practice continued through the 19th century; at one time there were more than 5,000 different types of banknotes issued by various commercial banks in America.

[116] Under the ensuing economic recovery, many aristocratic Genoese families, such as the Balbi, Doria, Grimaldi, Pallavicini, and Serra, amassed tremendous fortunes.

However, the modern visitor passing brilliant Mannerist and Baroque palazzo facades along Genoa's Strada Nova (now Via Garibaldi) or via Balbi cannot fail to notice that there was conspicuous wealth, which in fact was not Genoese but concentrated in the hands of a tightly knit circle of banker-financiers, true "venture capitalists".

Genoa's trade, however, remained closely dependent on control of Mediterranean sealanes, and the loss of Chios to the Ottoman Empire (1566), struck a severe blow.

The Genoese obtained a concession to exploit the port mainly for the slave trade of the new world on the Pacific, which lasted until the sacking and destruction of the original city in 1671.

[119][120] In the meantime in 1635 Don Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera, the then governor of Panama, had recruited Genoese, Peruvians, and Panamanians, as soldiers to wage war against Muslims in the Philippines and to found the city of Zamboanga upon the conquests of the Sultanates of Sulu and Maguindanao.

[122] The Genoese banker Ambrogio Spinola, Marquess of Los Balbases, for instance, raised and led an army that fought in the Eighty Years' War in the Netherlands in the early 17th century.

The Bankamericard, launched in 1958, became the first third-party credit card to acquire widespread use and to be accepted in shops and stores all over the United States, soon followed by Mastercard and American Express.