History of archaeology

In the 6th century BCE, Nabonidus of the Neo-Babylonian Empire excavated, surveyed and restored sites built more than a millennium earlier under Naram-sin of Akkad.

In the Song Empire (960–1279) of imperial China, Chinese scholar-officials unearthed, studied, and cataloged ancient artifacts, a native practice that continued into the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) before adoption of Western methods.

Khaemweset, a son of ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II, was known for his keen interest in identifying and restoring monuments of Egypt's past, such as Djoser's step pyramid.

Antiquarianism also focused on the empirical evidence that existed for the understanding of the past, encapsulated in the motto of the 18th-century antiquary Sir Richard Colt Hoare, "We speak from facts not theory".

[6] Neo-Confucian scholar-officials were generally concerned with archaeological pursuits in order to revive the use of ancient Shang, Zhou, and Han relics in state rituals.

For instance, the official, historian, poet, and essayist Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) compiled an analytical catalogue of ancient rubbings on stone and bronze.

[11][12] The Chong xiu Xuanhe bogutu (重修宣和博古圖) archaeological collection catalogue commissioned by Emperor Huizong of Song (r. 1100–1125) was widely reprinted in the 16th century during the Ming period,[13] but it was criticized by Hong Mai (1123–1202) for containing inaccuracies about Han dynasty artifacts.

[14] The 12th century Indian scholar Kalhana's writings involved recording of local traditions, examining manuscripts, inscriptions, coins and architectures, which is described as one of the earliest traces of archaeology.

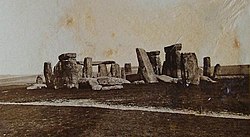

[22]English antiquarians of the 16th century including John Leland and William Camden conducted topographical surveys of England's countryside, drawing, describing and interpreting the monuments that they encountered.

[23][24] These individuals were frequently clergymen: many vicars recorded local landmarks within their parishes, details of the landscape and ancient monuments such as standing stones—even if they did not always understand the significance of what they were seeing.

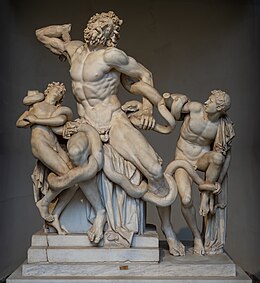

A very influential figure in the development of the theoretical and systematic study of the past through its physical remains was "the prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology," Johann Joachim Winckelmann.

[28] Winckelmann was a founder of scientific archaeology by first applying empirical categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the classical (Greek and Roman) history of art and architecture.

His original approach was based on detailed empirical examinations of artefacts from which reasoned conclusions could be drawn and theories developed about ancient societies.

In America, Thomas Jefferson, possibly inspired by his experiences in Europe, supervised the systematic excavation of a Native American burial mound on his land in Virginia in 1784.

The emperor took with him a force of 500 civilian scientists, specialists in fields such as biology, chemistry and languages, in order to carry out a full study of the ancient civilisation.

The work of Jean-François Champollion in deciphering the Rosetta Stone to discover the hidden meaning of hieroglyphics proved the key to the study of Egyptology.

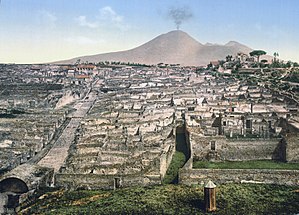

[29] However, prior to the development of modern techniques excavations tended to be haphazard; the importance of concepts such as stratification and context were completely overlooked.

[30] In the first half of the 19th century many other archaeological expeditions were organized; Giovanni Battista Belzoni and Henry Salt collected Ancient Egyptian artifacts for the British Museum, Paul Émile Botta excavated the palace of Assyrian ruler Sargon II, Austen Henry Layard unearthed the ruins of Babylon and Nimrud and discovered the Library of Ashurbanipal and Robert Koldeway and Karl Richard Lepsius excavated sites in the Middle East.

[31] Cunnington's work was funded by a number of patrons, the wealthiest of whom was Richard Colt Hoare, who had inherited the Stourhead estate from his grandfather in 1785.

The first reference to the use of a trowel on an archaeological site was made in a letter from Cunnington to Hoare in 1808, which describes John Parker using one in the excavation of Bush Barrow.

The idea of overlapping strata tracing back to successive periods was borrowed from the new geological and palaeontological work of scholars like William Smith, James Hutton and Charles Lyell.

In the third and fourth decade of the 19th century, archaeologists like Jacques Boucher de Perthes and Christian Jürgensen Thomsen began to put the artifacts they had found in chronological order.

He was also responsible for mentoring and training a whole generation of Egyptologists, including Howard Carter, who went on to achieve fame with the discovery of the tomb of 14th-century BCE pharaoh Tutankhamun.

The first stratigraphic excavation to reach wide popularity with the public was that of Hissarlik, on the site of ancient Troy, carried out by Heinrich Schliemann, Frank Calvert, Wilhelm Dörpfeld and Carl Blegen in the 1870s.