Science in the Renaissance

The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and continued up to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the invention of printing allowed a faster propagation of new ideas.

Historians like George Sarton and Lynn Thorndike criticized how the Renaissance affected science, arguing that progress was slowed for some amount of time.

By the early 15th century, an international search for ancient manuscripts was underway and would continue unabated until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, when many Byzantine scholars had to seek refuge in the West, particularly Italy.

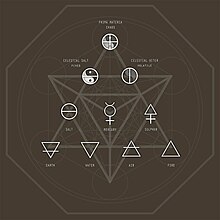

[5] Paracelsus was a chymist and physician of the Renaissance period who believed that, in addition to sulphur and mercury, salt served as one of the primary alchemical principles from which everything else was made.

[7] These lines of thinking directly conflicted with many long-held traditional beliefs, such as those popularized by Aristotle; however, Paracelsus was insistent that questioning principles of nature was essential to continue the general growth of knowledge.

[7] Despite its frequent basis in what may be considered scientific practices by modern standards, numerous factors caused chymistry as a discipline to remain separate from general academia until near the end of the Renaissance, when it finally began appearing as a portion of some university education.

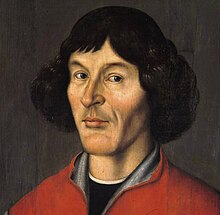

He died after completing only six books, however, and Regiomontanus continued the task, consulting a Greek manuscript brought from Constantinople by Cardinal Bessarion.

When it was published in 1496, the Epitome of the Almagest made the highest levels of Ptolemaic astronomy widely accessible to many European astronomers for the first time.

A comparison of his work with the Almagest shows that Copernicus was in many ways a Renaissance scientist rather than a revolutionary, because he followed Ptolemy's methods and even his order of presentation.

Much of the work of Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius, along with later authors such as Hero and Pappus, were copied and studied in both Byzantine culture and in Islamic centers of learning.

The greatest of all translation efforts, however, took place in the 15th and 16th centuries in Italy, as attested by the numerous manuscripts dating from this period currently found in European libraries.

Not only did humanists assist mathematicians with the retrieval of Greek manuscripts, they also took an active role in translating these work into Latin, often commissioned by religious leaders such as Nicholas V and Cardinal Bessarion.

Some mathematicians, such as Tartaglia and Luca Paccioli, welcomed and expanded on the medieval traditions of both Islamic scholars and people like Jordanus and Fibonnacci.

[14] The progress being made in math was complemented by advancements in physics, with people like Galileo attempting to bridge the gap between the two fields and question Aristotelian ideas.

[8]: 79–82 Galileo also contributed to the advancement of this field with a treatise on mechanics in 1593,[15] helping to develop ideas on relativity, freely falling bodies, and accelerated linear motion,[16] though he lacked the means to properly communicate his findings at the time.

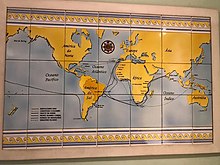

[15] Navigation was an important topic of the time, and many innovations were made that, with the introduction of better ships and applications of the compass, would later lead to geographical discoveries.

[8]: 89–91 The calculations involved in navigation proved to be difficult, with the technology of the time unable to accuately predict weather or determine one's geographic position.

[8]: 89–91 With the Renaissance came an increase in experimental investigation, principally in the field of dissection and body examination, thus advancing our knowledge of human anatomy.