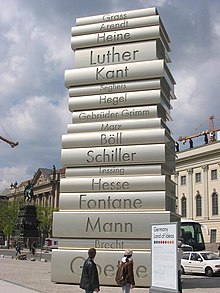

History of books

The Middle Ages saw the rise of illuminated manuscripts, intricately blending text and imagery, particularly during the Mughal era in South Asia under the patronage of rulers like Akbar and Shah Jahan.

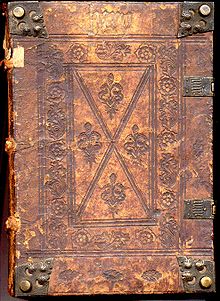

Prior to the invention of the printing press, made famous by the Gutenberg Bible, each text was a unique handcrafted valuable article, personalized through the design features incorporated by the scribe, owner, bookbinder, and illustrator.

The Late Modern Period introduced chapbooks, catering to a wider range of readers, and mechanization of the printing process further enhanced efficiency.

While discussions about the potential decline of physical books have surfaced, print media has proven remarkably resilient, continuing to thrive as a multi-billion dollar industry.

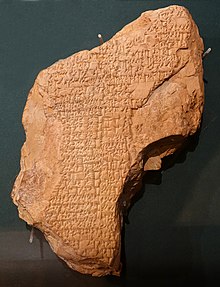

[6] Cuneiform was written in different languages, such as Sumerian, Akkadian, and Greek, for more than three thousand years, ending only when the Sassanian Empire conquered Babylon and forced the scribes to stop writing.

[6] After extracting the marrow from the stems of papyrus reed, a series of steps (humidification, pressing, drying, gluing, and cutting) produced media of variable quality, the best being used for sacred writing.

China's first recognizable books called jiance or jiandu, were made of rolls of thin split and dried bamboo bound together with hemp, silk, or leather.

For instance, Hitomi Hitsudai spent sixty years taking field notes on 499 types of edible flowers and animals for his book Honchō shokkan (The Culinary Mirror of the Realm).

These authors took into account the different social strata of their audience and had to learn "the common forms of reference that made the words and images of a text intelligible" to the layman.

Despite the vast depiction of landscape, governmental powers ensured areas that entailed sensitive subjects, such as military households, foreign affairs, Christianity, and other heterodox beliefs, and disturbing current events were kept out of public works.

[22] Despite these censors, public readings increased across Japan and created new markets that could be shared between the higher elites as well as middlebrow people, albeit with differing subject matter.

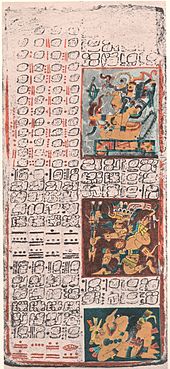

In Mesoamerica, information was recorded on long strips of paper, agave fibers, or animal hides, which were then folded and protected by wooden covers.

The Florentine Codex speaks about the culture religious cosmology and ritual practices, society, economics, and natural history of the Aztec people.

Usually, these tablets were used for everyday purposes (accounting, notes) and for teaching writing to children, according to the methods discussed by Quintilian in his Institutio Oratoria X Chapter 3.

The riddle reads: Some enemy deprived me of my life And took away my worldly strength, then wet me, dipped me in water, took me out again, set me in sunshine, where I quickly lost the hairs I had.

Then fingers folded me; the bird’s fine raiment traced often over me with useful drops across my brown domain, swallowed the tree-dye mixed up with water, stepped on me again leaving dark tracks.

[citation needed] From a political and religious point of view, books were censored very early: the works of Protagoras were burned because he was a proponent of agnosticism and argued that one could not know whether or not the gods existed.

Generally, cultural conflicts led to important periods of book destruction: in 303, the emperor Diocletian ordered the burning of Christian texts.

The spread of books, and attention to their cataloging and conservation, as well as literary criticism developed during the Hellenistic period with the creation of large libraries in response to the desire for knowledge exemplified by Aristotle.

Under Arab rule, these artisans enhanced their techniques for beating rag fibers and preparing the surface of the paper to be smooth and porous by utilizing starch.

The introduction of water-powered paper mills, the first certain evidence of which dates to the 11th century in Córdoba, Spain,[34] allowed for a massive expansion of production and replaced the laborious handcraft characteristic of both Chinese[35][36] and Muslim[35][37] papermaking.

[42] The conversion of members of the Mongol elite classes to Islam in the 13th century CE to form the Ilkhanate led to a surge in patronage for book production and distribution from Tabriz and Baghdad.

[48] Lithographic printmaking was introduced as a way of mechanical reproduction of text and image by the 19th century CE, shortly after its invention in the Kingdom of Bavaria.

[55] Following his exile into the Safavid Empire, in 1540 Babur's successor Humayun brought back artisans of illustrated Persian manuscripts to the Mughal court.

[56] He established a painting workshop adjacent to the royal library and atelier in Fatehpur Sikri in the late 15th century CE, allowing the production of the book and illustrated manuscript to occur more efficiently.

[56] Akbar's grandson Shah Jahan established a manuscript decoration tradition that included a strong emphasis on text than his predecessors, as well as margins filled with imagery of flowers and vegetation.

[55] Manuscript production had declined from its peak by the time of Shah Jahan's reign and book illustrators and artisans went on to be employed by the regional Rajasthani courts of Bikaner, Bundi and Kota.

Everything from myth and fairy tales to practical and medical advice and prayers contributed to a steady demand that helped spread literacy among the lower classes.

Among a series of developments that occurred in the 1990s, the spread of digital multimedia, which encodes texts, images, animations, and sounds in a unique and simple form was notable for the book publishing industry.

[65][66][67] A good deal of reference material, designed for direct access instead of sequential reading, as for example encyclopedias, exists less and less in the form of books and increasingly on the web.