History of urban planning

Archaeological evidence suggests that many Harrapan houses were laid out to protect from noise and to enhance residential privacy; many also had their own water wells, probably both for sanitary and for ritual purposes.

From about the late 8th century on, Greek city-states started to found colonies along the coasts of the Mediterranean, which were centred on newly created towns and cities with more or less regular orthogonal plans.

[18] Urban development in the early Middle Ages, characteristically focused on a fortress, a fortified abbey, or a (sometimes abandoned) Roman nucleus, occurred "like the annular rings of a tree",[19] whether in an extended village or the centre of a larger city.

Most of the new towns were to remain rather small (as for instance the bastides of southwestern France), but some of them became important cities, such as Cardiff, Leeds, 's-Hertogenbosch, Montauban, Bilbao, Malmö, Lübeck, Munich, Berlin, Bern, Klagenfurt, Alessandria, Warsaw and Sarajevo.

The newly founded towns often show a marked regularity in their plan form, in the sense that the streets are often straight and laid out at right angles to one another, and that the house lots are rectangular, and originally largely of the same size.

[citation needed] Florence was an early model of the new urban planning, which took on a star-shaped layout adapted from the new star fort, designed to resist cannon fire.

[23] This process occurred in cities, but ordinarily not in the industrial suburbs characteristic of this era (see Braudel, The Structures of Everyday Life), which remained disorderly and characterised by crowding and organic growth.

Inspired by the ideal of the Renaissance city, Pope Sixtus V's ambitious urban reform programme transformed the old environment to emulate the "long straight streets, wide regular spaces, uniformity and repetitiveness of structures, lavish use of commemorative and ornamental elements, and maximum visibility from both linear and circular perspective."

The Pope set no limit to his plans, and achieved much in his short pontificate, always carried through at top speed: the completion of the dome of St. Peter's; the loggia of Sixtus in the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano; the chapel of the Praesepe in Santa Maria Maggiore; additions or repairs to the Quirinal, Lateran and Vatican palaces; the erection of four obelisks, including that in Saint Peter's Square; the opening of six streets; the restoration of the aqueduct of Septimius Severus ("Acqua Felice"); the integration of the Leonine City in Rome as XIV Rione (Borgo).

An exception to this was in London after the Great Fire of 1666 when, despite many radical rebuilding schemes from architects such as John Evelyn and Christopher Wren, no large-scale redesigning was achieved due to the complexities of rival ownership claims.

This plan was opposed by residents and municipal authorities, who wanted a rapid reconstruction, did not have the resources for grandiose proposals, and resented what they considered the imposition of a new, foreign, architectural style.

[25] Keen to have a new and perfectly ordered city, the king commissioned the construction of big squares, rectilinear, large avenues and widened streets – the new mottos of Lisbon.

The street was designed by John Nash (who had been appointed to the Office of Woods and Forests in 1806 and previously served as an adviser to the Prince Regent) and by developer James Burton.

His objectives were to improve the health of the inhabitants, towards which the blocks were built around central gardens and orientated NW-SE to maximise the sunlight they received, and assist social integration.

Around 1900, theorists began developing urban planning models to mitigate the consequences of the industrial age, by providing citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments.

Modern zoning legislation and other tools such as compulsory purchase and land readjustment,[30] which enabled planners to legally demarcate sections of cities for different functions or determine the shape and depth of urban blocks, originated in Prussia, and spread to Britain, the US, and Scandinavia.

[32] Urban planning became professionalised at this period, with input from utopian visionaries as well as from the practical minded infrastructure engineers and local councillors combining to produce new design templates for political consideration.

[34] Legislation enabling the laying out of urban plans by municipalities and compulsory purchase powers were set out in the German Federal Building Line Act of 1875,[35] but the 1794 Allgemeines Landrecht already gave the local state authority, namely the police, the right to indicate Fluchtlinien, i.e. the boundaries of areas which were to be reserved for streets.

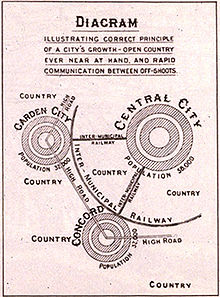

[41] His idealised garden city would house 32,000 people on a site of 6,000 acres (2,428 ha), planned on a concentric pattern with open spaces, public parks and six radial boulevards, 120 ft (37 m) wide, extending from the centre.

[45] In 1904, Raymond Unwin, a noted architect and town planner, along with his partner Richard Barry Parker, won the competition run by the First Garden City, Limited to plan Letchworth, an area 34 miles outside London.

The scheme's utopian ideals were that it should be open to all classes of people with free access to woods and gardens and that the housing should be of low density with wide, tree-lined roads.

The Tudor Walters Committee that recommended the building of housing estates after World War I incorporated the ideas of Howard's disciple Raymond Unwin, who demonstrated that homes could be built rapidly and economically whilst maintaining satisfactory standards for gardens, family privacy and internal spaces.

Le Corbusier hoped that politically minded industrialists in France would lead the way with their efficient Taylorist and Fordist strategies adopted from American industrial models to re-organise society.

[54] In 1925, Le Corbusier exhibited his Plan Voisin, in which he proposed to bulldoze most of central Paris north of the Seine and replace it with his sixty-story cruciform towers from the Contemporary City, placed within an orthogonal street grid and park-like green space.

Dating mainly from the years of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), when the city of Berlin was particularly progressive socially, politically and culturally, they are outstanding examples of the building reform movement that contributed to improving housing and living conditions for people with low incomes through innovative approaches to architecture and urban planning.

[61] By the late 1960s and early 1970s, many planners felt that modernism's clean lines and lack of human scale sapped vitality from the community, blaming them for high crime rates and social problems.

Residents in compact urban neighbourhoods drive fewer miles and have significantly lower environmental impacts across a range of measures compared with those living in sprawling suburbs.

In the new global situation, with the horizontal, low-density growth irreversibly dominant, and climate change already happening, they say it would be wiser to focus efforts on the resilience of whole city-regions, retrofitting the existing sprawl for sustainability and self-sufficiency, and investing heavily in 'green infrastructure'.

[71] Some planners argue that modern lifestyles use too many natural resources, polluting or destroying ecosystems, increasing social inequality, creating urban heat islands, and causing climate change.

[74] Experiences in Portland and Seattle have demonstrated that successful collaborative planning depends on a number of interrelated factors: the process must be truly inclusive, with all stakeholders and affected groups invited to the table; the community must have final decision-making authority; full government commitment (of both financial and intellectual resources) must be manifest; participants should be given clear objectives by planning staff, who facilitate the process by providing guidance, consultancy, expert opinions, and research; and facilitators should be trained in conflict resolution and community organisation.