History of virology

The history of virology – the scientific study of viruses and the infections they cause – began in the closing years of the 19th century.

The subsequent discovery and partial characterization of bacteriophages by Frederick Twort and Félix d'Herelle further catalyzed the field, and by the early 20th century many viruses had been discovered.

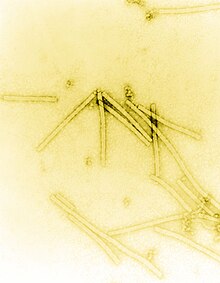

Viruses were demonstrated to be particles, rather than a fluid, by Wendell Meredith Stanley, and the invention of the electron microscope in 1931 allowed their complex structures to be visualised.

Despite his other successes, Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) was unable to find a causative agent for rabies and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected using a microscope.

[2] In 1876, Adolf Mayer, who directed the Agricultural Experimental Station in Wageningen, was the first to show that what he called "Tobacco Mosaic Disease" was infectious.

[3] In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck (1851–1931), a microbiology teacher at the Agricultural School in Wageningen repeated experiments by Adolf Mayer and became convinced that filtrate contained a new form of infectious agent.

[4] He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing and he called it a contagium vivum fluidum (soluble living germ) and re-introduced the word virus.

[3] Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by the American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley (1904–1971), who proved that they were in fact, particles.

[3] In the same year, 1898, Friedrich Loeffler (1852–1915) and Paul Frosch (1860–1928) passed the first animal virus through a similar filter and discovered the cause of foot-and-mouth disease.

[6] In 1881, Carlos Finlay (1833–1915), a Cuban physician, first conducted and published research that indicated that mosquitoes were carrying the cause of yellow fever,[7] a theory proved in 1900 by commission headed by Walter Reed (1851–1902).

During 1901 and 1902, William Crawford Gorgas (1854–1920) organised the destruction of the mosquitoes' breeding habitats in Cuba, which dramatically reduced the prevalence of the disease.

In 1926, he was invited to speak at a meeting organised by the Society of American Bacteriology where he said for the first time, "Viruses appear to be obligate parasites in the sense that their reproduction is dependent on living cells.

It is assumed that Dr. J. Buist of Edinburgh was the first person to see virus particles in 1886, when he reported seeing "micrococci" in vaccine lymph, though he had probably observed clumps of vaccinia.

[12] In the years that followed, as optical microscopes were improved "inclusion bodies" were seen in many virus-infected cells, but these aggregates of virus particles were still too small to reveal any detailed structure.

It was not until the invention of the electron microscope in 1931 by the German engineers Ernst Ruska (1906–1988) and Max Knoll (1887–1969),[13] that virus particles, especially bacteriophages, were shown to have complex structures.

[17] The discovery of RNA in the particles was important because in 1928, Fred Griffith (c. 1879–1941) provided the first evidence that its "cousin", DNA, formed genes.

[23][24] Between 1918 and 1921 d'Herelle discovered different types of bacteriophages that could infect several other species of bacteria including Vibrio cholerae.

[23] Since the early 1970s, bacteria have continued to develop resistance to antibiotics such as penicillin, and this has led to a renewed interest in the use of bacteriophages to treat serious infections.

Together with Delbruck they were jointly awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses".

[33] He excluded the possibility of a fungal infection and could not detect any bacterium and speculated that a "soluble, enzyme-like infectious principle was involved".

[34] He did not pursue his idea any further, and it was the filtration experiments of Ivanovsky and Beijerinck that suggested the cause was a previously unrecognised infectious agent.

[40] By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity, their ability to be filtered, and their requirement for living hosts.

[44] In 1941–42, George Hirst (1909–94) developed assays based on haemagglutination to quantify a wide range of viruses as well as virus-specific antibodies in serum.

[50] A major breakthrough came in 1931, when the American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture grew influenza and several other viruses in fertilised chickens' eggs.

Frank Macfarlane Burnet showed in the early 1950s that the virus recombines at high frequencies, and Hirst later, in 1962, deduced that it has a segmented genome.

The invention of a cell culture system for growing the virus enabled Jonas Salk (1914–1995) to make an effective polio vaccine.

[67] Reverse transcriptase, the key enzyme that retroviruses use to translate their RNA into DNA, was first described in 1970, independently by Howard Temin and David Baltimore (b.