Homosexuality in ancient Rome

Same-sex relations among women are far less documented[2] and, if Roman writers are to be trusted, female homoeroticism may have been very rare, to the point that Ovid, in the Augustine era describes it as "unheard-of".

[3] However, there is scattered evidence—for example, a couple of spells in the Greek Magical Papyri—which attests to the existence of individual women in Roman-ruled provinces in the later Imperial period who fell in love with members of the same sex.

[4] During the Republic, a Roman citizen's political liberty (libertas) was defined in part by the right to preserve his body from physical compulsion, including both corporal punishment and sexual abuse.

Lack of self-control, including in managing one's sex life, indicated that a man was incapable of governing others; too much indulgence in "low sensual pleasure" threatened to erode the elite male's identity as a cultured person.

Homoerotic themes occur throughout the works of poets writing during the reign of Augustus, including elegies by Tibullus[35] and Propertius,[36] several Eclogues of Vergil, especially the second, and some poems by Horace.

[40] Vergil describes their love as pius, linking it to the supreme virtue of pietas as possessed by the hero Aeneas himself, and endorsing it as "honorable, dignified and connected to central Roman values".

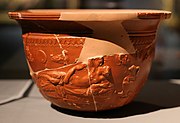

[50] Out of several hundred objects depicting images of sexual contact—from wall paintings and oil lamps to vessels of various types of material—only a small minority exhibits acts between males, and even fewer among females.

[52][54] The Warren Cup (discussed below) is an exception among homoerotic objects: it shows only male couples and may have been produced in order to celebrate a world of exclusive homosexuality.

[54] With some exceptions, Greek vase painting attributes desire and pleasure only to the active partner of homosexual encounters, the erastes, while the passive, or eromenos, seems physically unaroused and, at times, emotionally distant.

The "Roman" side of the cup shows a puer delicatus [fig., delicious boy], age 12 to 13, held for intercourse in the arms of an older male, clean-shaven and fit.

[76] Some terms, such as exoletus, specifically refer to an adult; Romans who were socially marked as "masculine" did not confine their same-sex penetration of male prostitutes or slaves to those who were "boys" under the age of 20.

[79] Cinaedus is a derogatory word denoting a male who was gender-deviant; his choice of sex acts, or preference in sexual partner, was secondary to his perceived deficiencies as a "man" (vir).

[80] Cinaedus is not equivalent to the English vulgarism "faggot",[83] except that both words can be used to deride a male considered deficient in manhood or with androgynous characteristics whom women may find sexually alluring.

[84] The clothing, use of cosmetics, and mannerisms of a cinaedus marked him as effeminate,[80] but the same effeminacy that Roman men might find alluring in a puer became unattractive in the physically mature male.

[96] Like the catamite or puer delicatus, the role of the concubine was regularly compared to that of Ganymede, the Trojan prince abducted by Jove (Greek Zeus) to serve as his cupbearer.

For even if there was a tight bond between the couple, the general social expectation was that pederastic affairs would end once the younger partner grew facial hair.

As such, when Martial celebrates in two of his epigrams (1.31 and 5.48) the relationship of his friend, the centurion Aulens Pudens, with his slave Encolpos, the poet more than once gives voice to the hope that the latter's beard come late, so that the romance between the pair may last long.

It derived from the unattested Greek adjective pathikos, from the verb paskhein, equivalent to the Latin deponent patior, pati, passus, "undergo, submit to, endure, suffer".

[122] Funeral inscriptions found in the ruins of the imperial household under Augustus and Tiberius also indicate that deliciae were kept in the palace and that some slaves, male and female, worked as beauticians for these boys.

Quintus Fabius Maximus Eburnus, a consul in 116 BC and later a censor known for his moral severity, earned his cognomen meaning "Ivory" (the modern equivalent might be "Porcelain") because of his fair good looks (candor).

[158] Although Cicero's sexual implications are clear, the point of the passage is to cast Antony in the submissive role in the relationship and to impugn his manhood in various ways; there is no reason to think that actual marriage rites were performed.

[155] Roman law addressed the rape of a male citizen as early as the 2nd century BC,[159] when it was ruled that even a man who was "disreputable and questionable" (famosus, related to infamis, and suspiciosus) had the same right as other free men not to have his body subjected to forced sex.

[160] The Lex Julia de vi publica,[161] recorded in the early 3rd century AD but probably dating from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar, defined rape as forced sex against "boy, woman, or anyone"; the rapist was subject to execution, a rare penalty in Roman law.

[166] The threat of one man to subject another to anal or oral rape (irrumatio) is a theme of invective poetry, most notably in Catullus's notorious Carmen 16,[167] and was a form of masculine braggadocio.

[181] The youngest officers, who still might retain some of the adolescent attraction that Romans favored in male–male relations, were advised to beef up their masculine qualities by not wearing perfume, nor trimming nostril and underarm hair.

A good-looking young recruit named Trebonius[183] had been sexually harassed over a period of time by his superior officer, who happened to be Marius's nephew, Gaius Lusius.

According to Roman studies scholar Craig Williams, the verses can also be read as, "a poetic soliloquy in which a woman ponders her own painful experiences with men and addresses herself in Catullan manner; the opening wish for an embrace and kisses express a backward-looking yearning for her man.

[208] In the "mock trial" exercise presented by the elder Seneca,[209] the young man (adulescens) was gang-raped while wearing women's clothes in public, but his attire is explained as his acting on a dare by his friends, not as a choice based on gender identity or the pursuit of erotic pleasure.

In several surviving examples of Greek and Roman sculpture, the love goddess pulls up her garments to reveal her male genitalia, a gesture that traditionally held apotropaic or magical power.

For example, Pliny the Elder notes that "there are even those who are born of both sexes, whom we call hermaphrodites, at one time androgyni" (andr-, "man", and gyn-, "woman", from the Greek),[216] and Philostratus offers a historical account of a congenital "eunuch".