Vertical and horizontal

In physics, engineering and construction, the direction designated as vertical is usually that along which a plumb-bob hangs.

Alternatively, a spirit level that exploits the buoyancy of an air bubble and its tendency to go vertically upwards may be used to test for horizontality.

On the surface of a smoothly spherical, homogenous, non-rotating planet, the plumb bob picks out as vertical the radial direction.

This fact has real practical applications in construction and civil engineering, e.g., the tops of the towers of a suspension bridge are further apart than at the bottom.

It is a non homogeneous, non spherical, knobby planet in motion, and the vertical not only need not lie along a radial, it may even be curved and be varying with time.

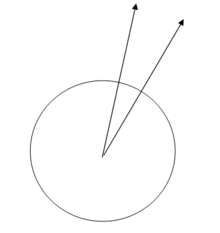

[9][10] Neglecting the curvature of the earth, horizontal and vertical motions of a projectile moving under gravity are independent of each other.

For example, even a projectile fired in a horizontal direction (i.e., with a zero vertical component) may leave the surface of the spherical Earth and indeed escape altogether.

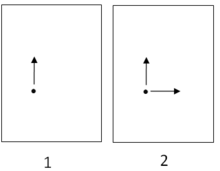

[13] In the context of a 1-dimensional orthogonal Cartesian coordinate system on a Euclidean plane, to say that a line is horizontal or vertical, an initial designation has to be made.

There is no special reason to choose the horizontal over the vertical as the initial designation: the two directions are on par in this respect.

This dichotomy between the apparent simplicity of a concept and an actual complexity of defining (and measuring) it in scientific terms arises from the fact that the typical linear scales and dimensions of relevance in daily life are 3 orders of magnitude (or more) smaller than the size of the Earth.

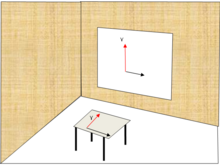

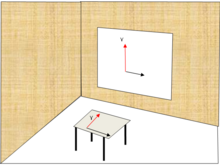

This is purely conventional (although it is somehow 'natural' when drawing a natural scene as it is seen in reality), and may lead to misunderstandings or misconceptions, especially in an educational context.