Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham

By his marriage to a daughter of Ralph, Earl of Westmorland, Humphrey was related to the powerful Neville family and to many of the leading aristocratic houses of the time.

[10][11] When Stafford was later asked by the royal council if the King had left any final instructions regarding the governance of Normandy, he claimed that he had been too upset at the time to be able to remember.

[1] For example, in October 1425, Archbishop of Canterbury Henry Chichele, Peter, Duke of Coimbra and Stafford helped to negotiate an end to a burst of violence that had erupted in London between followers of the two rivals.

[12] Stafford was also chosen by the council to inform Beaufort—now a Cardinal—that he was to absent himself from Windsor until it was decided if he could carry out his traditional duty of Prelate to the Order of the Garter now that Pope Martin V had promoted him.

[25] He also attended the interrogation of Joan of Arc in Rouen in 1431; at some point during these proceedings, a contemporary alleged, Stafford attempted to stab her and had to be physically restrained.

[28][29] The county was valued at 800 marks per annum,[30][d] although the historian Michael Jones has suggested that due to the war, in real terms "the amount of revenue that could be extracted ... must have been considerably lower".

Here he maintained a permanent staff of at least forty people, as well as a large stable, and it was especially well-placed for recruiting retainers in the Welsh Marches, Staffordshire, and Cheshire.

[1] "His landed resources matched his titles", explained Albert Compton-Reves, scattered as they were throughout England, Wales and Ireland,[43] with only the King and Richard, Duke of York wealthier.

[52][f] In the late medieval period, all great lords created an affinity between themselves and groups of supporters, who often lived and travelled with them for purposes of mutual benefit and defence,[54] and Humphrey Stafford was no exception.

[58] His affinity was probably composed along the lines laid out by royal ordinance at the time which dictated the nobility should be accompanied by no more than 240 men, including "forty gentlemen, eighty yeomen and a variety of lesser individuals",[47] suggested T. B. Pugh, although in peacetime Stafford would have required far fewer.

[73] Although the expedition's purpose was to end the siege of Calais by Philip, Duke of Burgundy, the Burgundians had withdrawn before they arrived,[74] leaving behind a quantity of cannon for the English to seize.

[75] Subsequent peace talks in France occupied Stafford throughout 1439, and in 1442 he was appointed Captain of Calais[1] and the Risbanke fort, and was indented to serve for the next decade.

[51][84] In 1442, he had been on the committee that investigated and convicted Gloucester's wife, Eleanor Cobham, of witchcraft,[51] and five years later he arrested the Duke at Bury St Edmunds on 18 February 1447 for treason.

[91] He was one of the lords commissioned to arrest the rebels as part of a forceful government response on 6 June 1450, and he acted as a negotiator with the insurgents at Blackheath ten days later.

[93] After the eventual defeat of the rebellion, Buckingham headed an investigatory commission designed to pacify rebellious Kent,[94] and in November that year he rode noisily through London—with a retinue of around 1,500 armed men—with the King and other peers, in a demonstration of royal authority intended to deter potential troublemakers in the future.

[106] Buckingham may well by now have been expecting war to break out, because the same year he ordered the purchase of 2,000 cognizances—his personal badge of the 'Stafford knot'[107]—even though strictly the distribution of livery was illegal.

[108] Following the King's recovery, York was either dismissed from or resigned his protectorship, and together with his Neville allies, withdrew from London to their northern estates.

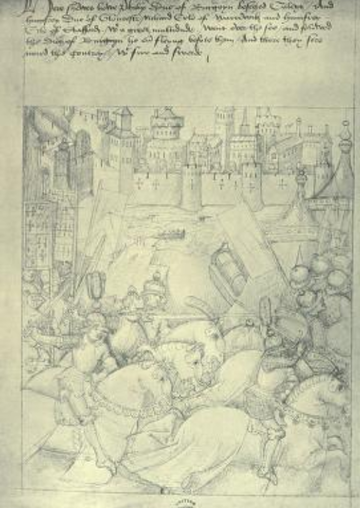

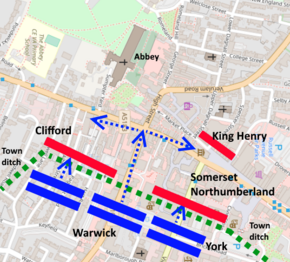

The King, with a smaller force[109] that nonetheless included important nobles such as Somerset, Northumberland, Clifford and Buckingham and his son Humphrey, Earl of Stafford,[110] was likewise marching from Westminster to Leicester, and in the early morning of 22 May, royal scouts reported the Yorkists as being only a few hours away.

The decision to head for the town and not make a stand straight away may have been a tactical error;[109] the contemporary Short English Chronicle describes how the Lancastrians "strongly barred and arrayed for defence" immediately after they arrived.

[114] His strategy was to play for time,[115] both to prepare the town's defences[116] and to await the arrival of loyalist bishops, who could be counted on to bring the moral authority of the church to bear on the Yorkists.

[118] Buckingham made what John Gillingham described as an "insidiously tempting suggestion"[119] that the Yorkists mull over the King's responses in Hatfield or Barnet overnight.

[110] The Yorkists realised what Buckingham—"prevaricating with courtesy", says Armstrong[121]—was trying to do and battle commenced while negotiations were still taking place: Richard, Earl of Warwick, launched a surprise attack at around ten o'clock in the morning.

[119] Although the defences that Buckingham had organised successfully checked the Yorkists' initial advance,[123] Warwick took his force through gardens and houses to attack the Lancastrians in the rear.

A chronicler reported that some Yorkist soldiers, intent on looting, entered the abbey to kill Buckingham, but that the Duke was saved by York's personal intervention.

[130] York now had the political upper hand, made himself Constable of England and kept the King as a prisoner, returning to the role of Protector when Henry became ill again.

[132] Here, with other lords, he tried to persuade the King to impose a settlement, and at the same time declared that anyone who resorted to violence would receive "ther deserte"[133]—which included any who attacked York.

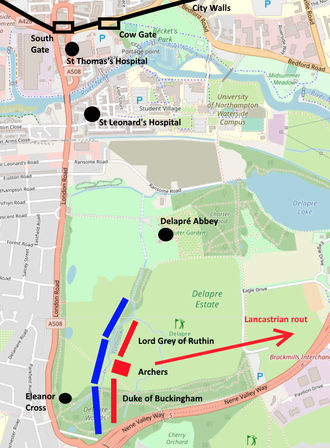

[141] They immediately marched on, and entered London; the King, with Buckingham and other lords, was in Coventry, and on hearing of the earls' arrival, moved the court to Northampton.

[145] Personal animosity as much as political judgment was responsible for Buckingham's attitude, possibly, suggests Rawcliffe, the result of Warwick's earlier rent evasion.

[162] Rawcliffe has suggested that although he was inevitably going to be involved in the high politics of the day, Buckingham "lacked the necessary qualities ever to become a great statesman or leader ... [he] was in many ways an unimaginative and unlikeable man".

[188] However, the lost play could instead have been about the equally eventful career of Prince Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1390–1447), the youngest son of Henry IV of England.