Hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging,[1][2] that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, especially wild edible plants but also insects, fungi, honey, bird eggs, or anything safe to eat, or by hunting game (pursuing or trapping and killing wild animals, including catching fish).

[6] However, an attempted verification of this study found "that multiple methodological failures all bias their results in the same direction...their analysis does not contradict the wide body of empirical evidence for gendered divisions of labor in foraging societies".

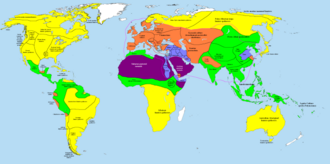

[10] It remained the only mode of subsistence until the end of the Mesolithic period some 10,000 years ago, and after this was replaced only gradually with the spread of the Neolithic Revolution.

[16] Early humans in the Lower Paleolithic lived in forests and woodlands, which allowed them to collect seafood, eggs, nuts, and fruits besides scavenging.

[17] Scientists have demonstrated that the evidence for early human behaviors for hunting versus carcass scavenging vary based on the ecology, including the types of predators that existed and the environment.

Some hunter-gatherer cultures, such as the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast and the Yokuts, lived in particularly rich environments that allowed them to be sedentary or semi-sedentary.

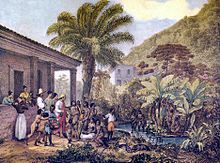

[28][29][30] For example, the San people or "Bushmen" of southern Africa have social customs that strongly discourage hoarding and displays of authority, and encourage economic equality via sharing of food and material goods.

[46] A 2006 study suggests that the sexual division of labor was the fundamental organizational innovation that gave Homo sapiens the edge over the Neanderthals, allowing our ancestors to migrate from Africa and spread across the globe.

[50] In 2018, 9000-year-old remains of a female hunter along with a toolkit of projectile points and animal processing implements were discovered at the Andean site of Wilamaya Patjxa, Puno District in Peru.

[45] However, an attempted verification of this study found "that multiple methodological failures all bias their results in the same direction...their analysis does not contradict the wide body of empirical evidence for gendered divisions of labor in foraging societies".

[7] At the 1966 "Man the Hunter" conference, anthropologists Richard Borshay Lee and Irven DeVore suggested that egalitarianism was one of several central characteristics of nomadic hunting and gathering societies because mobility requires minimization of material possessions throughout a population.

At the same conference, Marshall Sahlins presented a paper entitled, "Notes on the Original Affluent Society", in which he challenged the popular view of hunter-gatherers lives as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short", as Thomas Hobbes had put it in 1651.

According to Sahlins, ethnographic data indicated that hunter-gatherers worked far fewer hours and enjoyed more leisure than typical members of industrial society, and they still ate well.

Other scholars also assert that hunter-gatherer societies were not "affluent" but suffered from extremely high infant mortality, frequent disease, and perennial warfare.

[56] This study, however, exclusively examined modern hunter-gatherer communities, offering limited insight into the exact nature of social structures that existed prior to the Neolithic Revolution.

In cold and heavily forested environments, edible plant foods and large game are less abundant and hunter-gatherers may turn to aquatic resources to compensate.

Marine food probably did not start becoming prominent in the diet until relatively recently, during the Late Stone Age in southern Africa and the Upper Paleolithic in Europe.

[58] Fat is important in assessing the quality of game among hunter-gatherers, to the point that lean animals are often considered secondary resources or even starvation food.

[71][72][73][clarification needed] Doron Shultziner and others have argued that we can learn a lot about the life-styles of prehistoric hunter-gatherers from studies of contemporary hunter-gatherers—especially their impressive levels of egalitarianism.

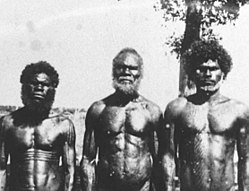

[74] There are nevertheless a number of contemporary hunter-gatherer peoples who, after contact with other societies, continue their ways of life with very little external influence or with modifications that perpetuate the viability of hunting and gathering in the 21st century.

[8] One such group is the Pila Nguru (Spinifex people) of Western Australia, whose land in the Great Victoria Desert has proved unsuitable for European agriculture (and even pastoralism).

[76][77] The Savanna Pumé of Venezuela also live in an area that is inhospitable to large scale economic exploitation and maintain their subsistence based on hunting and gathering, as well as incorporating a small amount of manioc horticulture that supplements, but is not replacing, reliance on foraged foods.

[78] Evidence suggests big-game hunter-gatherers crossed the Bering Strait from Asia (Eurasia) into North America over a land bridge (Beringia), that existed between 47,000 and 14,000 years ago.

[79] Around 18,500–15,500 years ago, these hunter-gatherers are believed to have followed herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.

[81][82] Hunter-gatherers would eventually flourish all over the Americas, primarily based in the Great Plains of the United States and Canada, with offshoots as far east as the Gaspé Peninsula on the Atlantic coast, and as far south as Chile, Monte Verde.

This early Paleo-Indian period lithic reduction tool adaptations have been found across the Americas, utilized by highly mobile bands consisting of approximately 25 to 50 members of an extended family.

Individual groups started to focus on resources available to them locally, however, and thus archaeologists have identified a pattern of increasing regional generalization, as seen with the Southwest, Arctic, Poverty Point, Dalton and Plano traditions.

These regional adaptations would become the norm, with reliance less on hunting and gathering, with a more mixed economy of small game, fish, seasonally wild vegetables and harvested plant foods.

[85][86] Scholars like Kat Anderson have suggested that the term Hunter-gatherer is reductive because it implies that Native Americans never stayed in one place long enough to affect the environment around them.