Hurricane preparedness in New Orleans

The Corps of Engineers also designed a Lake Pontchartrain Hurricane Barrier to shield the city with flood gates like those which protect the Netherlands from the North Sea.

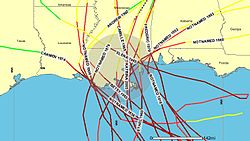

[6] In 2004, a Corps of Engineers study was done on the cost and feasibility of protecting southeast Louisiana from a major Category 5 hurricane, including construction of floodgate structures and raising existing levees.

[7] In 2001, the Houston Chronicle published a story which predicted that a severe hurricane striking New Orleans, "would strand 250,000 people or more, and probably kill one of 10 left behind as the city drowned under 20 feet (6.1 m) of water.

"[6] In 2002, The Times Picayune published a feature covering various scenarios, including a Category 5 hurricane hitting the city from the south.

One article in the series concluded that hundreds of thousands would be left homeless, and it would take months to dry out the area and begin to make it liveable.

[8] Many concerns focus around the fact that the city lies below sea level with a levee system that was designed for hurricanes of no greater intensity than Category 3.

[11] There was relatively minor damage in the city; however, there was still some moderate flooding, with portions of Interstate 10 being closed due to rising water and the French Quarter being almost a foot underwater.

The study identified the problem: the New Orleans area is like a bowl, surrounded by levees which are strongest along the outer Mississippi and primarily intended to contain river flooding.

[18][19] On January 25, 2005, the Louisiana Sea Grant forum discussed additional results of several simulations of strong hurricanes hitting New Orleans.

However, Cindy's winds gusted to 70 mph (110 km/h) in the city, knocking branches off trees and causing New Orleans' largest blackout since Hurricane Betsy in 1965.

[29] Disorganization began when the Louisiana Governor declined a proposal from the White House to put National Guard troops under the control of the federal government.

[29] President George W. Bush and Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff were also criticized for failures on the federal level as well as with his leadership role.

[30] FEMA chief Michael D. Brown admitted on the 1 year anniversary of landfall that there was no plan,[31] and claimed that in the immediate aftermath of the disaster White House officials told him to lie to put a more positive spin on the Federal response.

After a typical hurricane hit the region, the plan would be for disaster relief forces to reach the city by overland routes.

Since there was no flood-based federal nor state plan, heavy lift capacity helicopters that could have brought 16 tons of water, medical and food per flight were nowhere to be found.

On the day after the Hurricane, Michael Chertoff invoked the National Response Plan, transferring emergency authority to the Department of Homeland Security.

Private volunteers with boats assisted with rescue in great numbers, but significant Federal response was largely absent until 5 days after the disaster.

[36] Hurricane Ernesto in 2006 originally threatened Louisiana before hitting Florida, causing early preparations and rising oil prices.

A senior Corps official made an off-hand estimate that this project would require approximately $1 Billion dollars and would take 20 years, stating "It's possible to protect New Orleans from a Category 5 hurricane... we've got to start.

Strock also said that he did not believed that funding levels contributed to the disaster, commenting that, "the intensity of this storm simply exceeded the design capacity of this levee."

The New York Times, in particular, published several editorials criticizing the large size of the $17 Billion Corps budget, and called for the Senate to cut, "pork," in S. 728, which would have provided $512 Million in funding for hurricane protection projects in southern Louisiana.

[citation needed] Just after Hurricane Katrina hit, there was some concern expressed that government officials had placed an overemphasis on disaster recovery, while neglecting the process of pre-planning and preparation.

If the Corps built a 1-in-500-year levee system in New Orleans, Ivan van Heerden, deputy director of Louisiana State University's Hurricane Center, says, it would cost $30 billion.

For structures in hazardous areas and residents who do not relocate, the committee recommended major floodproofing measures such as elevating the first floor of buildings to at least the 100-year flood level.

[57] The weight of large buildings and infrastructure and the leaching of water, oil and gas from beneath the surface across the region have also contributed to the problem.

However, an unintended consequence of the levees was that natural silt deposits from the Mississippi River were unable to replenish the delta, causing the coastal wetlands of Louisiana to wash away and the city of New Orleans to sink even deeper.

The problem with the wetlands was further worsened by salt water intrusion caused by the canals dug by the oil companies and private individuals in this marshland.

Hurricanes moving over fragmenting marshes toward the New Orleans area can retain more strength, and their winds and large waves pack more speed and destructive power.

The problem also is slowly eroding levee protection, cutting off evacuation routes sooner and putting dozens of communities and valuable infrastructure at risk of being wiped out by the flooding.

State and federal officials have recently pushed a $14 billion plan to rebuild wetlands over the next 30 years, to be funded by oil and gas royalties, called Coast 2050.