Hydrogel

[citation needed] Chemical hydrogels can result in strong reversible or irreversible gels due to the covalent bonding.

[10][11][12] Physical hydrogels usually have high biocompatibility, are not toxic, and are also easily reversible by simply changing an external stimulus such as pH, ion concentration (alginate) or temperature (gelatine); they are also used for medical applications.

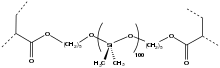

Hydrogels are prepared using a variety of polymeric materials, which can be divided broadly into two categories according to their origin: natural or synthetic polymers.

Natural polymers for hydrogel preparation include hyaluronic acid, chitosan, heparin, alginate, gelatin and fibrin.

[20] There are two suggested mechanisms behind physical hydrogel formation, the first one being the gelation of nanofibrous peptide assemblies, usually observed for oligopeptide precursors.

The second mechanism involves non-covalent interactions of cross-linked domains that are separated by water-soluble linkers, and this is usually observed in longer multi-domain structures.

[21] Tuning of the supramolecular interactions to produce a self-supporting network that does not precipitate, and is also able to immobilize water which is vital for to gel formation.

[22][23] The typical mechanism of gelation involves the oligopeptide precursors self-assemble into fibers that become elongated, and entangle to form cross-linked gels.

This reaction will cease if the light source is removed, allowing the amount of crosslinks formed in the hydrogel to be controlled.

In this, the solution is frozen for a few hours, then thawed at room temperature, and the cycle is repeated until a strong and stable hydrogel is formed.

A water solution of gelatin forms an hydrogel at temperatures below 37–35 °C, as Van der Waals interactions between collagen fibers become stronger than thermal molecular vibrations.

[28] Peptide based hydrogels possess exceptional biocompatibility and biodegradability qualities, giving rise to their wide use of applications, particularly in biomedicine;[2] as such, their physical properties can be fine-tuned in order to maximise their use.

[36] Furthermore, aromatic interactions play a key role in hydrogel formation as a result of π- π stacking driving gelation, shown by many studies.

As responsive "smart materials", hydrogels can encapsulate chemical systems which upon stimulation by external factors such as a change of pH may cause specific compounds such as glucose to be liberated to the environment, in most cases by a gel–sol transition to the liquid state.

[44] In order to describe the time-dependent creep and stress-relaxation behavior of hydrogel, a variety of physical lumped parameter models can be used.

[40] These modeling methods vary greatly and are extremely complex, so the empirical Prony Series description is commonly used to describe the viscoelastic behavior in hydrogels.

Several factors contribute to the toughness of a hydrogel including composition, crosslink density, polymer chain structure, and hydration level.

[46] Additionally, higher crosslinking density generally leads to increased toughness by restricting polymer chain mobility and enhancing resistance to deformation.

This occurs because the polymer chains within a hydrogel rearrange, and the water molecules are displaced, and energy is stored as it deforms in mechanical extension or compression.

[50] When the mechanical stress is removed, the hydrogel begins to recover its original shape, but there may be a delay in the recovery process due to factors like viscoelasticity, internal friction, etc.

Hysteresis within a hydrogel is influenced by several factors including composition, crosslink density, polymer chain structure, and temperature.

For example, in the biomedical field, LCST hydrogels are being investigated as drug delivery systems due to being injectable (liquid) at room temp and then solidifying into a rigid gel upon exposure to the higher temperatures of the human body.

[54] There are many other stimuli that hydrogels can be responsive to, including: pH, glucose, electrical signals, light, pressure, ions, antigens, and more.

[7] Other additives, such as nanoparticles and microparticles, have been shown to significantly modify the stiffness and gelation temperature of certain hydrogels used in biomedical applications.

One unique processing technique is through the formation of multi-layered hydrogels to create a spatially-varying matrix composition and by extension, mechanical properties.

This technique can be useful in creating hydrogels that mimic articular cartilage, enabling a material with three separate zones of distinct mechanical properties.

Utilizing both the freeze-casting and salting-out processing techniques on poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels to induce hierarchical morphologies and anisotropic mechanical properties.

While maintaining a water content of over 70%, these hydrogels' toughness values are well above those of water-free polymers such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Kevlar, and synthetic rubber.

[91][92] Materials such as collagen, chitosan, cellulose, and poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) have been implemented extensively for drug delivery to organs such as eye,[93] nose, kidneys,[94] lungs,[95] intestines,[96] skin[97] and brain.

[2] Future work is focused on reducing toxicity, improving biocompatibility, expanding assembly techniques[98] Hydrogels have been considered as vehicles for drug delivery.