Hyksos

In the Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt written by the Greco-Egyptian priest and historian Manetho in the 3rd century BC, the term Hyksos is used ethnically to designate people of probable West Semitic, Levantine origin.

[13] They have been credited with introducing several technological innovations to Egypt, such as the horse and chariot, as well as the khopesh (sickle sword) and the composite bow, a theory which is disputed.

The term "Hyksos" is derived, via the Greek Ὑκσώς (Hyksôs), from the Egyptian expression 𓋾𓈎𓈉 (ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣswt or ḥqꜣw-ḫꜣswt, "heqau khasut"), meaning "rulers [of] foreign lands".

[27] "It is now commonly accepted in academic publications that the term Ḥqꜣ-Ḫꜣswt refers only to the individual foreign rulers of the late Second Intermediate Period,"[28] especially of the Fifteenth Dynasty, rather than a people.

[6][39] All other texts in the Egyptian language do not call the Hyksos by this name, instead referring to them as Asiatics (ꜥꜣmw), with the possible exception of the Turin King List in a hypothetical reconstruction from a fragment.

[48] According to Anna-Latifa Mourad, the Egyptian application of the term ꜥꜣmw to the Hyksos could indicate a range of backgrounds, including newly arrived Levantines or people of mixed Levantine-Egyptian origin.

[49] Due to the work of Manfred Bietak, which found similarities in architecture, ceramics and burial practices, scholars currently favor a northern Levantine origin of the Hyksos.

A study of dental traits by Nina Maaranen and Sonia Zakrzewski in 2021 on 90 people of Avaris indicated that individuals defined as locals and non-locals were not ancestrally different from one another.

The results were in line with the archaeological evidence, suggesting Avaris was an important hub in the Middle Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean trade network, welcoming people from beyond its borders.

[57] The MacGregor plaque, an early Egyptian tablet dating to 3000 BC records "The first occasion of striking the East", with the picture of Pharaoh Den smiting a Western Asiatic enemy.

[61] As recorded by Josephus, Manetho describes the beginning of Hyksos rule thus: A people of ignoble origin from the east, whose coming was unforeseen, had the audacity to invade the country, which they mastered by main force without difficulty or even battle.

Having overpowered the chiefs, they then savagely burnt the cities, razed the temples of the gods to the ground, and treated the whole native population with the utmost cruelty, massacring some, and carrying off the wives and children of others into slavery (Contra Apion I.75-77).

[68][69] Manfred Bietak argues that Hyksos "should be understood within a repetitive pattern of the attraction of Egypt for western Asiatic population groups that came in search of a living in the country, especially the Delta, since prehistoric times.

"[52] Bietak interprets a stela of Neferhotep III to indicate that Egypt was overrun by roving mercenaries around the time of the Hyksos ascension to power.

[80] The site of Tell Basta (Bubastis), at the confluence of the Pelusiac and Tanitic branches of the Nile, contains monuments to the Hyksos kings Khyan and Apepi, but little other evidence of Levantine habitation.

[83] In the Wadi Tumilat, Tell el-Maskhuta shows a great deal of Levantine pottery and an occupation history closely correlated to the Fifteenth Dynasty,[87] nearby Tell el-Rataba and Tell el-Sahaba show possible Hyksos-style burials and occupation,[88] Tell el-Yahudiyah, located between Memphis and the Wadi Tumilat, contains a large earthwork that the Hyksos may have built, as well as evidence of Levantine burials from as early as the Thirteenth Dynasty,[89] as well as characteristic Hyksos-era pottery known as Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware The Hyksos settlements in the Wadi Tumilat would have provided access to Sinai, the southern Levant, and possibly the Red Sea.

[66] The sites Tell el-Kabir, Tell Yehud, Tell Fawziya, and Tell Geziret el-Faras are noted by scholars other than Mourad to contain "elements of 'Hyksos culture'", but there is no published archaeological material for them.

[13] Some objects might suggest a Hyksos presence in Upper Egypt, but they may have been Theban war booty or attest simply to short-term raids, trade, or diplomatic contact.

[74] Three years later, c. 1542 BC,[98] Seqenenre Tao's successor Kamose initiated a campaign against several cities loyal to the Hyksos, the account of which is preserved on three monumental stelae set up at Karnak.

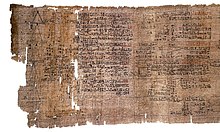

[98] Ahmose I continued the war against the Hyksos, most likely conquering Memphis, Tjaru, and Heliopolis early in his reign, the latter two of which are mentioned in an entry of the Rhind mathematical papyrus.

[123] Various other archaeological sources also provide names of rulers with the Hyksos title,[124] however, the majority of kings from the second intermediate period are attested once on a single object, with only three exceptions.

[70][132][133] Recently, archaeological finds have suggested that Khyan may have been a contemporary of the Thirteenth Dynasty pharaoh Sobekhotep IV, potentially making him an early rather than a late Hyksos ruler.

[97] An intercepted letter between Apepi and the King of Kingdom of Kerma, also called Kush, to the south of Egypt recorded on the Carnarvon Tablet has been interpreted as evidence of an alliance between the Hyksos and Kermans.

[96] According to his second stele, Kamose was effectively caught between the campaign for the siege of Avaris in the north and the offensive of Kerma in the south; it is unknown whether or not the Kermans and Hyksos were able to combine forces against him.

[83] According to the Kamose stelae, the Hyksos imported "chariots and horses, ships, timber, gold, lapis lazuli, silver, turquoise, bronze, axes without number, oil, incense, fat and honey".

[194] Josephus's account of Manetho connects the expulsion of the Hyksos to another event two hundred years later, in which a group of lepers led by the priest Osarseph were expelled from Egypt to the abandoned Avaris.

[200] Scholars such as Jan Assmann and Donald Redford, for instance, have suggested that the story of the biblical exodus may have been wholly or partially inspired by the expulsion of the Hyksos.

[201][202][203] Archaeologists Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argue that the exodus narrative perhaps evolved from vague memories of the Hyksos expulsion, spun to encourage resistance to the 7th century domination of Judah by Egypt.

[217] Kim Ryholt notes that these measures are unique to the Hyksos rulers and "may therefore have been a direct result of what seems to have been deliberate attempt to obliterate the memory of their kingship after their defeat.

[231] The discovery of the Hyksos in the 19th century, and their study following the decipherment of ancient Egyptian scripts, led to various theories about their history, origin, ethnicity and appearance, often illustrated with picturesque and imaginative details.

|