Hyperbolic trajectory

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics, a hyperbolic trajectory or hyperbolic orbit is the trajectory of any object around a central body with more than enough speed to escape the central object's gravitational pull.

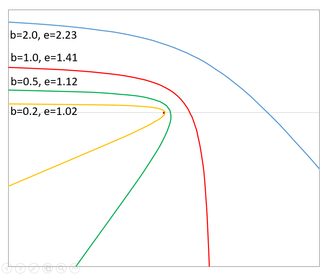

The name derives from the fact that according to Newtonian theory such an orbit has the shape of a hyperbola.

In more technical terms this can be expressed by the condition that the orbital eccentricity is greater than one.

Planetary flybys, used for gravitational slingshots, can be described within the planet's sphere of influence using hyperbolic trajectories.

Like an elliptical orbit, a hyperbolic trajectory for a given system can be defined (ignoring orientation) by its semi major axis and the eccentricity.

The following table lists the main parameters describing the path of body following a hyperbolic trajectory around another under standard assumptions and the formula connecting them.

) is not immediately visible with a hyperbolic trajectory but can be constructed as it is the distance from periapsis to the point where the two asymptotes cross.

The semi major axis is directly linked to the specific orbital energy (

is characteristic energy, commonly used in planning interplanetary missions Note that the total energy is positive in the case of a hyperbolic trajectory (whereas it is negative for an elliptical orbit).

the asymptotes are more than 120° apart, and the periapsis distance is greater than the semi major axis.

The angle between the direction of periapsis and an asymptote from the central body is the true anomaly as distance tends to infinity (

With bodies experiencing gravitational forces and following hyperbolic trajectories it is equal to the semi-minor axis of the hyperbola.

In the situation of a spacecraft or comet approaching a planet, the impact parameter and excess velocity will be known accurately.

The distance of closest approach, or periapsis distance, is given by: So if a comet approaching Earth (effective radius ~6400 km) with a velocity of 12.5 km/s (the approximate minimum approach speed of a body coming from the outer Solar System) is to avoid a collision with Earth, the impact parameter will need to be at least 8600 km, or 34% more than the Earth's radius.

A body approaching Jupiter (radius 70000 km) from the outer Solar System with a speed of 5.5 km/s, will need the impact parameter to be at least 770,000 km or 11 times Jupiter radius to avoid collision.

If the mass of the central body is not known, its standard gravitational parameter, and hence its mass, can be determined by the deflection of the smaller body together with the impact parameter and approach speed.

Because typically all these variables can be determined accurately, a spacecraft flyby will provide a good estimate of a body's mass.

): Note that this means that a relatively small extra delta-v above that needed to accelerate to the escape speed results in a relatively large speed at infinity.

The converse is also true - a body does not need to be slowed by much compared to its hyperbolic excess speed (e.g. by atmospheric drag near periapsis) for velocity to fall below escape velocity and so for the body to be captured.

is: In context of the two-body problem in general relativity, trajectories of objects with enough energy to escape the gravitational pull of the other no longer are shaped like a hyperbola.

Nonetheless, the term "hyperbolic trajectory" is still used to describe orbits of this type.