In the Land of Invented Languages

Okrent explores the motivations for creating a language, the challenges faced by such projects, and the outcomes of a number of high-profile conlangs.

Okrent describes her personal experiences learning and interacting with these languages and their speakers, and provides historical and linguistic analyses of their structures and features.

[3] Okrent is fluent in American Sign Language and speaks or understands some level of Hungarian, Esperanto, and Brazilian Portuguese.

Ben Prist, the Australian creator of Vela, simply could not understand why his language was being ignored, and blamed some kind of anti-Australian conspiracy.

She discusses contemporaries such as Thomas Urquhart, himself interested in language construction, who wrote a manuscript on his attempt titled "Gold out of Dung".

[8] Wilkins endeavoured to catalogue subjects by their traits and build words accordingly; Okrent gives the example of zitα ("dog"), which is built from the particles for "clawed, rapacious, oblong-headed, land-dwelling beast of docile disposition".

[9] Okrent discusses the difficulty of translating between Wilkins' language and any other, due to his desire to represent every concept with an individual word.

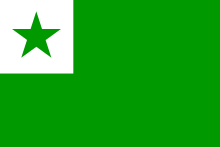

Though Esperanto too saw language schisms, resulting in the creation of Ido, it remained dominant due to its speakers' devotion to Zamenhof.

[11] She argues that Esperantists form a distinct culture, and draws parallels between it and Modern Hebrew, itself a consciously revived language.

He attempted to learn them, thinking they could be a base for a "universal language", but felt after failed study that a pictogram system would be a better foundation for such a project.

Bliss designed his Blissymbols writing system to minimize ambiguity, which he hoped would end falsehoods, propaganda, and other matters he considered flaws of language.

When Bliss emigrated to Australia in the 1940s, he evangelized Blissymbols to linguists and academic publishers to little avail, and came to think his system would never receive the popularity he felt it deserved.

They found the system revealed unexpected communicative capacities in children assumed to have profound intellectual impairments, and sought out Bliss to assist them with basing a formal education program around Blissymbols.

While he was first overjoyed by the recognition, the relationship grew increasingly strained as the school diverged from what he considered the system's intent; Okrent gives the examples of him castigating the teachers for combining the "food" and "out" symbols to make "picnic", when he intended that combination to mean "restaurant", and of disparaging their use of formal grammatical concepts such as "nouns" and "verbs".

She ascribes this attention to Brown's scientific mindset in presenting his language as a specific experiment, and to his more grounded claims than utopian predecessors.

Lojban is an exceptionally specific language that Okrent compares to speech "filtered through the sensibilities of a bratty, literal-minded eight-year-old".

Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review, conferred to books of "truly outstanding quality",[20] and described it as a "delightful tour of linguistic hubris".

[22] An in-depth review in the Zócalo Public Square referred to In the Land of Invented Languages as "fascinating, accessible, and offer[ing] interesting insights into what we say and how we say it".

The review took note of Okrent's depth of research, including analyses of languages difficult or obscure enough to have very few speakers, such as Lojban.

[23] Edwin Turner of Biblioklept recommended the book, stating it "confidently traverses the thin line between pop nonfiction and academic linguistics".

Usona Esperantisto, the official publication of Esperanto-USA, described Okrent as an "icon" in an interview and focused on the book's positive reception in Esperantist circles.