Photon

[2] The modern photon concept originated during the first two decades of the 20th century with the work of Albert Einstein, who built upon the research of Max Planck.

While Planck was trying to explain how matter and electromagnetic radiation could be in thermal equilibrium with one another, he proposed that the energy stored within a material object should be regarded as composed of an integer number of discrete, equal-sized parts.

[9] In 1905, Albert Einstein published a paper in which he proposed that many light-related phenomena—including black-body radiation and the photoelectric effect—would be better explained by modelling electromagnetic waves as consisting of spatially localized, discrete energy quanta.

[5] The name was suggested initially as a unit related to the illumination of the eye and the resulting sensation of light and was used later in a physiological context.

The reverse process, pair production, is the dominant mechanism by which high-energy photons such as gamma rays lose energy while passing through matter.

[36] Sharper upper limits on the mass of light have been obtained in experiments designed to detect effects caused by the galactic vector potential.

Since particle models cannot easily account for the refraction, diffraction and birefringence of light, wave theories of light were proposed by René Descartes (1637),[41] Robert Hooke (1665),[42] and Christiaan Huygens (1678);[43] however, particle models remained dominant, chiefly due to the influence of Isaac Newton.

[44] In the early 19th century, Thomas Young and August Fresnel clearly demonstrated the interference and diffraction of light, and by 1850 wave models were generally accepted.

[10] In 1909[53] and 1916,[55] Einstein showed that, if Planck's law regarding black-body radiation is accepted, the energy quanta must also carry momentum p = h / λ , making them full-fledged particles.

The answer to this question occupied Albert Einstein for the rest of his life,[57] and was solved in quantum electrodynamics and its successor, the Standard Model.

Einstein's 1905 predictions were verified experimentally in several ways in the first two decades of the 20th century, as recounted in Robert Millikan's Nobel lecture.

[58] However, before Compton's experiment[56] showed that photons carried momentum proportional to their wave number (1922),[full citation needed] most physicists were reluctant to believe that electromagnetic radiation itself might be particulate.

In part, the change can be traced to experiments such as those revealing Compton scattering, where it was much more difficult not to ascribe quantization to light itself to explain the observed results.

[59] Even after Compton's experiment, Niels Bohr, Hendrik Kramers and John Slater made one last attempt to preserve the Maxwellian continuous electromagnetic field model of light, the so-called BKS theory.

[62] A few physicists persisted[63] in developing semiclassical models in which electromagnetic radiation is not quantized, but matter appears to obey the laws of quantum mechanics.

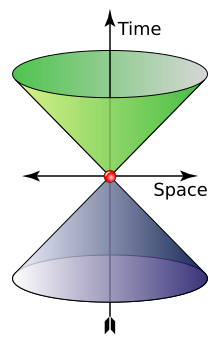

A single photon passing through a double slit has its energy received at a point on the screen with a probability distribution given by its interference pattern determined by Maxwell's wave equations.

[72] Another difficulty is finding the proper analogue for the uncertainty principle, an idea frequently attributed to Heisenberg, who introduced the concept in analyzing a thought experiment involving an electron and a high-energy photon.

[73][74] The uncertainty principle applies to situations where an experimenter has a choice of measuring either one of two "canonically conjugate" quantities, like the position and the momentum of a particle.

[76] In 1924, Satyendra Nath Bose derived Planck's law of black-body radiation without using any electromagnetism, but rather by using a modification of coarse-grained counting of phase space.

[77] Einstein showed that this modification is equivalent to assuming that photons are rigorously identical and that it implied a "mysterious non-local interaction",[78][79] now understood as the requirement for a symmetric quantum mechanical state.

Ironically, Max Born's probabilistic interpretation of the wave function[93][94] was inspired by Einstein's later work searching for a more complete theory.

However, Debye's approach failed to give the correct formula for the energy fluctuations of black-body radiation, which were derived by Einstein in 1909.

In such quantum field theories, the probability amplitude of observable events is calculated by summing over all possible intermediate steps, even ones that are unphysical; hence, virtual photons are not constrained to satisfy

The unification of the photon with W and Z gauge bosons in the electroweak interaction was accomplished by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg, for which they were awarded the 1979 Nobel Prize in physics.

[108] However, if experimentally probed at very short distances, the intrinsic structure of the photon appears to have as components a charge-neutral flux of quarks and gluons, quasi-free according to asymptotic freedom in QCD.

In a particle picture, the slowing can instead be described as a blending of the photon with quantum excitations of the matter to produce quasi-particles known as polaritons.

A classic example is the molecular transition of retinal (C20H28O), which is responsible for vision, as discovered in 1958 by Nobel laureate biochemist George Wald and co-workers.

Semiconductor charge-coupled device chips use a similar effect: an incident photon generates a charge on a microscopic capacitor that can be detected.

For example, the emission spectrum of a gas-discharge lamp can be altered by filling it with (mixtures of) gases with different electronic energy level configurations.

This is the basis of fluorescence resonance energy transfer, a technique that is used in molecular biology to study the interaction of suitable proteins.