South African Border War

Following several years of unsuccessful petitioning through the United Nations and the International Court of Justice for Namibian independence from South Africa, SWAPO formed the PLAN in 1962 with material assistance from the Soviet Union, China, and sympathetic African states such as Tanzania, Ghana, and Algeria.

[26] The state of war between South Africa and Angola briefly ended with the short-lived Lusaka Accords, but resumed in August 1985 as both PLAN and UNITA took advantage of the ceasefire to intensify their own guerrilla activity, leading to a renewed phase of FAPLA combat operations culminating in the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.

[38] During the South African general election, 1948, the National Party was swept into power, newly appointed Prime Minister Daniel Malan prepared to adopt a more aggressive stance concerning annexation, and Louw was named ambassador to the UN.

[40] The Good Offices Committee proposed a partition of the mandate, allowing South Africa to annex the southern portion while either granting independence to the north, including the densely populated Ovamboland region, or administering it as an international trust territory.

[43] A year before SWAPO made the decision to send its first SWALA recruits abroad for guerrilla training, South Africa established fortified police outposts along the Caprivi Strip for the express purpose of deterring insurgents.

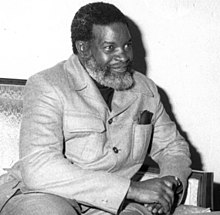

[51] Nujoma personally directed two exiles in Dar es Salaam, Lucas Pohamba and Elia Muatale, to return to South West Africa, infiltrate Ovamboland and send back more potential recruits for SWALA.

[51] In December 1971, Jannie de Wet, Commissioner for the Indigenous Peoples of South West Africa, sparked off a general strike by 15,000 Ovambo workers in Walvis Bay when he made a public statement defending the territory's controversial contract labour regulations.

[51] They attacked tribal headmen, vandalised stock control posts and government offices, and tore down about a hundred kilometres of fencing along the border, which they claimed obstructed itinerant Ovambos from grazing their cattle freely.

[60] While acknowledging that a significant percentage of the strikers were SWAPO members and supporters, the party's acting president Nathaniel Maxuilili noted that reform of South West African labour laws had been a longstanding aspiration of the Ovambo workforce, and suggested the strike had been organised shortly after the crucial ICJ ruling because they hoped to take advantage of its publicity to draw greater attention to their grievances.

[67] The three movements had all participated in the Angolan War of Independence and shared a common goal of liberating the country from colonial rule, but also claimed unique ethnic support bases, different ideological inclinations, and their own conflicting ties to foreign parties and governments.

[68] Within days of the Alvor Agreement, the Central Intelligence Agency launched its own programme, Operation IA Feature, to arm the FNLA, with the stated objective of "prevent[ing] an easy victory by Soviet-backed forces in Angola".

[70] SWAPO's closer affiliation and proximity to the MPLA may have influenced its concurrent slide to the left;[81] the party adopted a more overtly Marxist discourse, such as a commitment to a classless society based on the ideals and principles of scientific socialism.

[14] In order to reduce the likelihood of a South African attack, the training camps were sited near Cuban or FAPLA military installations, with the added advantage of being able to rely on the logistical and communications infrastructure of PLAN's allies.

[1] The system was backed by roving patrols drawn from Eland armoured car squadrons, motorised infantry, canine units, horsemen and scrambler motorcycles for mobility and speed over rough terrain; local San trackers, Ovambo paramilitaries, and South African special forces.

[90][97] 32 Battalion regularly sent teams recruited from ex-FNLA militants and led by white South African personnel into an authorised zone up to fifty kilometres deep in Angola; it could also dispatch platoon-sized reaction forces of similar composition to attack vulnerable PLAN targets.

[92] The three PLAN regional headquarters each developed their own forces which resembled standing armies with regard to the division of military labour, incorporating various specialties such as counter-intelligence, air defence, reconnaissance, combat engineering, sabotage, and artillery.

[102] Additionally, photographs of the parade ground taken by a Swedish reporter just prior to the raid depicted children and women in civilian clothing, but also uniformed PLAN guerrillas and large numbers of young men of military age.

[109] The resolution "condemned strongly the racist regime of South Africa for its premeditated, persistent, and sustained armed invasions of the People's Republic of Angola, which constitute a flagrant violation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country as well as a serious threat to international peace and security".

[112] President Reagan and his Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester Crocker adopted a policy of constructive engagement with the Botha government, restored military attachés to the US embassy in South Africa, and permitted SADF officers to receive technical training in the US.

[105] Operation Sceptic, then the largest combined arms offensive undertaken by South Africa since World War II, was launched in June against a PLAN base at Chifufua, over a hundred and eighty kilometres inside Angola.

[105] Operation Protea was mounted on an even larger scale and inflicted heavier PLAN casualties; unlike Sceptic, it was to involve significant FAPLA losses as well as the seizure of substantial amounts of Angolan military hardware and supplies.

[134] According to General Georg Meiring, commander of the SADF in South West Africa, Askari would serve the purpose of a preemptive strike aimed at eliminating the large numbers of PLAN insurgents and stockpiles of weapons being amassed for the annual rainy season infiltration.

[91] The SADF believed that a covert sabotage operation was possible, as long as the destruction was not attributable to South Africa and a credible cover story could be used to link the attack to a domestic Angolan movement such as UNITA or the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC).

[144] In its place, therefore, the other popular option was promulgated, which was to focus chiefly on fighting PLAN, the primary threat within the geographical limits of South West Africa proper, and attempting to intimidate Angola in the form of punitive cross-border raids, thus assuming an essentially defensive posture.

[10] To FAPLA, the experience of planning and executing an operation of such massive proportions was relatively new, but the Soviet military mission was convinced that a decade of exhaustive training on its part had created an army capable of undertaking a complex multi-divisional offensive.

[150] As Cuban and MK sources had predicted, the commitment of regular ground troops alongside UNITA was authorised, albeit on the condition that strict control would be exercised over combat operations at the highest level of government to ensure that political and diplomatic requirements meshed with the military ones.

[160] On multiple occasions the combined UNITA and SADF forces launched unsuccessful offensives which became bogged down in minefields along narrow avenues of approach and were abandoned when the attackers came under heavy fire from the Cuban and FAPLA artillerymen west of the Cuito River.

[163] FAPLA MiGs flew reconnaissance missions in search of the G5 and G6 howitzers, forcing the South African artillery crews to resort to increasingly elaborate camouflage and take the precaution of carrying out their bombardments after dark.

[128] In a notable departure from its previous foreign policy stance, the Soviet Union disclosed it too was weary of the Angolan and South West African conflicts and was prepared to assist in a peace process—even one conducted on the basis of Cuban linkage.

[167] Reformist Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, also wished to reduce defence expenditures, including the enormous open-ended commitment of military aid to FAPLA, and was more open to a political settlement accordingly.