Indian independence movement

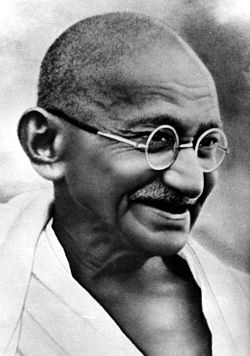

Female leaders like Sarojini Naidu, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Pritilata Waddedar, and Kasturba Gandhi promoted the emancipation of Indian women and their participation in the freedom struggle.

Local legends state that he survived two earlier attempts at hanging, and that the Nawab feared Yusuf Khan would come back to life and so had his body dismembered and buried in different locations around Tamil Nadu.

[19][20][21][22] More than 100 years of such escalating rebellions created grounds for a large, impactful, millenarian movement in Eastern India that again shook the foundations of British rule in the region, under the leadership of Birsa Munda.

They reached Delhi on 11 May, set the company's toll house on fire, and marched into the Red Fort, where they asked the Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, to become their leader and reclaim his throne.

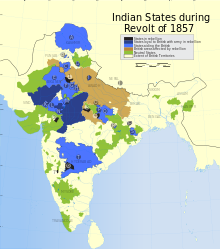

In a royal proclamation made to the people of India, Queen Victoria promised equal opportunity of public service under British law, and also pledged to respect the rights of native princes.

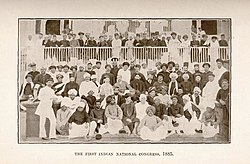

[54] However, this period of history is still crucial because it represented the first political mobilisation of Indians, coming from all parts of the subcontinent and the first articulation of the idea of India as one nation, rather than a collection of independent princely states.

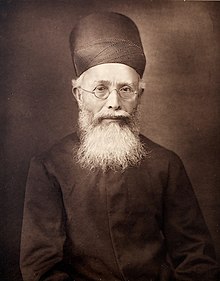

[55] The work of men like Swami Vivekananda, Ramakrishna, Sri Aurobindo, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, Subramanya Bharathy, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Rabindranath Tagore and Dadabhai Naoroji, as well as women such as the Scots–Irish Sister Nivedita, spread the passion for rejuvenation and freedom.

[56] Attacks by Hindu reformers against religious conversion, cow slaughter, and the preservation of Urdu in Arabic script deepened their concerns of minority status and denial of rights if the Congress alone were to represent the people of India.

During this time, Bengali Hindu nationalists like Sri Aurobindo, Bhupendranath Datta, and Bipin Chandra Pal began writing virulent newspaper articles challenging the legitimacy of British rule in India in publications such as Jugantar and Sandhya, and were charged with sedition.

In Bengal, Anushilan Samiti, led by brothers Aurobindo and Barin Ghosh organised a number of attacks of figureheads of the Raj, culminating in the attempt on the life of a British judge in Muzaffarpur.

Involving revolutionary underground in Bengal and headed by Rash Behari Bose along with Sachin Sanyal, the conspiracy culminated on the attempted assassination on 23 December 1912, when the ceremonial procession moved through the Chandni Chowk suburb of Delhi.

Nevertheless, Jinnah was instrumental in the passing of the Child Marriages Restraint Act, the legitimisation of the Muslim waqf (religious endowments) and was appointed to the Sandhurst committee, which helped establish the Indian Military Academy at Dehradun.

Support from the Congress Party was primarily offered on the hopes that Britain would repay such loyal assistance with substantial political concessions—if not immediate independence or at least dominion status following the war, then surely its promise soon after the Allies achieved victory.

The prospect that subversive violence would have an effect on a popular war effort drew support from the Indian population for special measures against anti-colonial activities in the form of Defence of India Act 1915.

The plot originated at the onset of World War I, between the Ghadar Party in the United States, the Berlin Committee in Germany, the Indian revolutionary underground in British India and the German Foreign Office through the consulate in San Francisco.

After the end of the war, fear of a second Ghadarite uprising led to the recommendations of the Rowlatt Acts and thence the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.The first Christmas Day plot was a conspiracy made by the Indian revolutionary movement in 1909: during the year-ending holidays, the Governor of Bengal organised at his residence a ball in the presence of the Viceroy, the Commander-in-Chief and all the high-ranking officers and officials of the Capital (Calcutta).

In keeping with his predecessor Otto (William Oskarovich) von Klemm, a friend of Lokamanya Tilak, on 6 February 1910, M. Arsenyev, the Russian Consul-General, wrote to St Petersburg that it had been intended to "arouse in the country a general perturbation of minds and, thereby, afford the revolutionaries an opportunity to take the power in their hands.

Nominally headed by the exiled Indian prince Raja Mahendra Pratap, the expedition was a joint operation of Germany and Turkey and was led by the German Army officers Oskar Niedermayer and Werner Otto von Hentig.

Other consequences included the formation of the Rowlatt Committee to investigate sedition in India as influenced by Germany and Bolshevism, and changes in the Raj's approach to the Indian independence movement immediately after World War I.

The means of achieving the proposed measures were later enshrined in the Government of India Act, 1919, which introduced the principle of a dual-mode of administration, or diarchy, in which both elected Indian legislators and, appointed British officials shared power.

In response to agitation in Amritsar, Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer blocked the main, and only entrance, and ordered troops under his command to fire into an unarmed and unsuspecting crowd of some 15,000 men, women, and children.

Although this came too late to influence the framing of the new Government of India Act 1919, the movement enjoyed widespread popular support, and the resulting unparalleled magnitude of disorder presented a serious challenge to foreign rule.

However, people like Mahakavi Subramanya Bharathi, Vanchinathan, and Neelakanda Brahmachari played a major role from Tamil Nadu in both self-rule struggle and fighting for equality for all castes and communities.

The Kolkata session of the Indian National Congress asked the British government to accord India dominion status by December 1929, or face a countrywide civil disobedience movement.

The Indian revolutionary underground began gathering momentum through the first decade of the 20th century, with groups arising in Bengal, Maharashtra, Odisha, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and the Madras Presidency including what is now called South India.

[113] In the former case, it was the educated, intelligent and dedicated youth of the urban middle class Bhadralok community that came to form the "classic" Indian revolutionary,[113] while the latter had an immense support base in the rural and military society of Punjab.

The Samiti was involved in a number of noted incidences of revolutionary terrorism against British interests and administration in India within the decade of its founding, including early attempts to assassinate Raj officials whilst led by Ghosh brothers.

The violence and radical philosophy revived in the 1930s, when revolutionaries of the Samiti and the HSRA were involved in the Chittagong armoury raid and the Kakori conspiracy and other attempts against the administration in British India and Raj officials.

Inspired by the patriotic zeal of revolutionaries in Bengal, Raju raided police stations in and around Chintapalle, Rampachodavaram, Dammanapalli, Krishna Devi Peta, Rajavommangi, Addateegala, Narsipatnam and Annavaram.

Along with this, the assessment may be made that it described in crystal clear terms to the government that the British Indian Armed forces could no longer be universally relied upon for support in crisis, and even more it was more likely itself to be the source of the sparks that would ignite trouble in a country fast slipping out of the scenario of political settlement.