Indian Rebellion of 1857

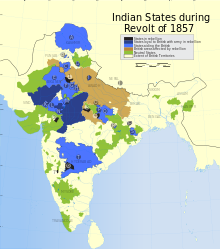

[k][7][10] The large princely states, Hyderabad, Mysore, Travancore, and Kashmir, as well as the smaller ones of Rajputana, did not join the rebellion, serving the British, in the Governor-General Lord Canning's words, as "breakwaters in a storm".

Since the sepoys from Bengal – many of whom had fought against the Company in the Battles of Plassey and Buxar – were now suspect in British eyes, Hastings recruited farther west from the high-caste rural Rajputs and Bhumihar of Awadh and Bihar, a practice that continued for the next 75 years.

As the extent of the East India Company's jurisdiction expanded with victories in wars or annexation, the soldiers were now expected not only to serve in less familiar regions, such as in Burma, but also to make do without the "foreign service" remuneration that had previously been their due.

The nobility, many of whom had lost titles and domains under the Doctrine of Lapse, which refused to recognise the adopted children of princes as legal heirs, felt that the company had interfered with a traditional system of inheritance.

Rebel leaders such as Nana Sahib and the Rani of Jhansi belonged to this group; the latter, for example, was prepared to accept East India Company supremacy if her adopted son was recognised as her late husband's heir.

[57] "Utilitarian and evangelical-inspired social reform",[58] including the abolition of sati[59][60] and the legalisation of widow remarriage were considered by many—especially the British themselves[61]—to have caused suspicion that Indian religious traditions were being "interfered with", with the ultimate aim of conversion.

The official Blue Books, East India (Torture) 1855–1857, laid before the House of Commons during the sessions of 1856 and 1857, revealed that Company officers were allowed an extended series of appeals if convicted or accused of brutality or crimes against Indians.

In the early years of Company rule, it tolerated and even encouraged the caste privileges and customs within the Bengal Army, which recruited its regular infantry soldiers almost exclusively amongst the landowning Rajputs and Brahmins of the Bihar and Oudh regions.

On 26 February 1857 the 19th Bengal Native Infantry (BNI) regiment became concerned that new cartridges they had been issued were wrapped in paper greased with cow and pig fat, which had to be opened by mouth thus affecting their religious sensibilities.

At Ambala in particular, which was a large military cantonment where several units had been collected for their annual musketry practice, it was clear to General Anson, Commander-in-Chief of the Bengal Army, that some sort of rebellion over the cartridges was imminent.

However, he issued no general orders making this standard practice throughout the Bengal Army and, rather than remain at Ambala to defuse or overawe potential trouble, he then proceeded to Simla, the cool hill station where many high officials spent the summer.

[76] While the action of the sepoys in freeing their 85 imprisoned comrades appears to have been spontaneous, some civilian rioting in the city was reportedly encouraged by Kotwal (chief police officer) Dhan Singh Gurjar.

It was a strong walled city located only forty miles away, it was the ancient capital and present seat of the nominal Mughal Emperor and finally there were no British troops in garrison there in contrast to Meerut.

Fearing that the arsenal, which contained large stocks of arms and ammunition, would fall intact into rebel hands, the nine British Ordnance officers there had opened fire on the sepoys, including the men of their own guard.

[97] The most influential member of Ahl-i-Hadith ulema in Delhi, Maulana Sayyid Nazir Husain Dehlvi, resisted pressure from the mutineers to call for a jihad and instead declared in favour of British rule, viewing the Muslim-British relationship as a legal contract which could not be broken unless their religious rights were breached.

Although the rebels produced some natural leaders such as Bakht Khan, whom the Emperor later nominated as commander-in-chief after his son Mirza Mughal proved ineffectual, for the most part they were forced to look for leadership to rajahs and princes.

Contemporary sources report that nearly all the Gurjar villages between Meerut and Delhi participated in the revolt, in some cases with support from Jullundur, and it was not until late July that, with the help of local Jats, and the princely states, the British managed to regain control of the area.

He had relied on his own prestige and his cordial relations with local landholder and hereditary prime minister Nana Sahib to thwart rebellion, and took comparatively few measures to prepare fortifications and lay in supplies and ammunition.

[citation needed] Other British accounts[122][123][124] state that indiscriminate punitive measures were taken in early June, two weeks before the murders at the Bibighar (but after those at both Meerut and Delhi), specifically by Lieutenant Colonel James George Smith Neill of the Madras Fusiliers, commanding at Allahabad, while moving towards Cawnpore.

In October, another larger army under the new Commander-in-Chief, Sir Colin Campbell, was finally able to relieve the garrison and on 18 November, they evacuated the defended enclave within the city, the women and children leaving first.

[126] General Dhir Shamsher Kunwar Rana, the youngest brother of Jung Bahadur, also led the Nepalese forces in various parts of India including Lucknow, Benares and Patna.

[citation needed] After being driven from Jhansi and Kalpi, on 1 June 1858 Rani Lakshmi Bai and a group of Maratha rebels captured the fortress city of Gwalior from the Scindia rulers, who were British allies.

[136] A siege soon ensued – eighteen civilians and 50 loyal sepoys from the Bengal Military Police Battalion under the command of Herwald Wake, the local magistrate, defended the house against artillery and musketry fire from an estimated 2000 to 3000 mutineers and rebels.

[145] At one stage, faced with the need to send troops to reinforce the besiegers of Delhi, the Commissioner of the Punjab (Sir John Lawrence) suggested handing the coveted prize of Peshawar to Dost Mohammad Khan of Afghanistan in return for a pledge of friendship.

Ahmed Khan was killed but the insurgents found a new leader in Mahr Bahawal Fatyana, who maintained the uprising for three months until Government forces penetrated the jungle and scattered the rebel tribesmen.

[152] The British quickly moved to send two companies from the 40th Madras Native Infantry from Cuttack on 10 October, and after a forced march reached Khinda on 5 November, only to find the place abandoned as the rebels retreated to the jungle.

[158][159] A particular act of cruelty on behalf of the British troops at Cawnpore included forcing many Muslim or Hindu rebels to eat pork or beef, as well as licking buildings freshly stained with blood of the dead before subsequent public hangings.

[159] Practices of torture included "searing with hot irons...dipping in wells and rivers till the victim is half suffocated... squeezing the testicles...putting pepper and red chillies in the eyes or introducing them into the private parts of men and women...prevention of sleep...nipping the flesh with pinners...suspension from the branches of a tree...imprisonment in a room used for storing lime..."[160] British soldiers also committed sexual violence against Indian women as a form of retaliation against the rebellion.

On the economy it was now believed that the previous attempts by the company to introduce free market competition had undermined traditional power structures and bonds of loyalty placing the peasantry at the mercy of merchants and moneylenders.

"[citation needed] Acting on these sentiments, Lord Ripon, viceroy from 1880 to 1885, extended the powers of local self-government and sought to remove racial practices in the law courts by the Ilbert Bill.