Indian maritime history

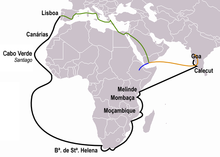

[10][11] On orders of Manuel I of Portugal, four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, continuing to the eastern coast of Africa to Malindi to sail across the Indian Ocean to Calicut by 1498.

[citation needed] The region around the Indus river began to show visible increase in both the length and the frequency of maritime voyages by 3000 BCE.

[15] Mesopotamian inscriptions indicate that Indian traders from the Indus valley—carrying copper, hardwoods, ivory, pearls, carnelian, and gold—were active in Mesopotamia during the reign of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2300 BCE).

[1] Gosch & Stearns write on the Indus Valley's pre-modern maritime travel:[16] Evidence exists that Harappans were bulk-shipping timber and special woods to Sumer on ships and luxury items such as lapis lazuli.

Archaeological research at sites in Mesopotamia, Bahrain, and Oman has led to the recovery of artefacts traceable to the Indus Valley civilisation, confirming the information on the inscriptions.

Among the most important of these objects are stamp seals carved in soapstone, stone weights, and colourful carnelian beads....Most of the trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley was indirect.

[18] Modern oceanographers have observed that the Harappans must have possessed great knowledge relating to tides in order to build such a dock on the ever-shifting course of the Sabarmati, as well as exemplary hydrography and maritime engineering.

[19] This knowledge also enabled them to select Lothal's location in the first place, as the Gulf of Khambhat has the highest tidal amplitude and ships can be sluiced through flow tides in the river estuary.

[22] Recent excavations at Berenike in Egypt have confirmed, there was a small community of Indian Buddhists at Alexandria, the greatest of all Roman ports.

[23] A large number of significant finds have been made providing evidence of the cargo from the Malabar Coast and the presence of Tamil people from South India and Jaffna being at this last outpost of the Roman Empire.

Pliny famously mentions the expenditure of one million sestertii every year on goods such as pepper, fine cloth and gems from the southern coasts of India.

In turn Tamil literature from the Classical period mentions foreign ships arriving for trade and paying in gold for products.

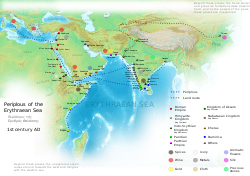

[32] The Periplus Maris Erythraei describes Greco—Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens, topaz, coral, storax, frankincense, vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine" in exchange for "costus, bdellium, lycium, nard, turquoise, lapis lazuli, Seric skins, cotton cloth, silk yarn, and indigo".

[6] Traces of Indian influences are visible in Roman works of silver and ivory, or in Egyptian cotton and silk fabrics used for sale in Europe.

[36] This route caused the intermixing of many artistic and cultural influences, Hellenistic, Iranian, Indian and Chinese, Greco-Buddhist art represents one such vivid examples of this interaction.

[39] Despite its association with China in recent centuries, the Maritime Silk Route was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia, Tamil merchants in India and Southeast Asia, Greco-Roman merchants in East Africa, India, Ceylon and Indochina, and by Persian and Arab traders in the Arabian Sea and beyond.

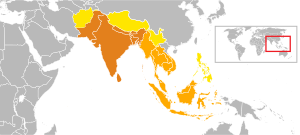

[41] The Maritime Silk Road developed from the earlier Austronesian spice trade networks of Islander Southeast Asians with Sri Lanka and Southern India (established 1000 to 600 BCE).

[42][43] Kalinga (in 3rd century BCE was annexed by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka) and Vijayanagara Empire (1336-1646) also established footholds in Malaya, Sumatra and Western Java.

[45] Textiles from India were in demand in Egypt, East Africa, and the Mediterranean between the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, and these regions became overseas markets for Indian exports.

[29] In Java and Borneo, the introduction of Indian culture created a demand for aromatics, and trading posts here later served Chinese and Arab markets.

[47] After reaching either the Indian or the Sri Lankan ports, products were sometimes shipped to East Africa, where they were used for a variety of purposes including burial rites.

[47] Indian spice exports find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850), al-Ghafiqi (1150 CE), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (14th century).

[49] Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden paid tribute in form of musk, camphor, ambergris and sandalwood to Ibn Ziyad, the sultan of Yemen.

[59][60][61] The Tang dynasty (618–907) of China, the Srivijaya empire in Maritime Southeast Asia under the Sailendras, and the Abbasid caliphate at Baghdad were the main trading partners.

Books written by Chinese monks like Wan Chen and Hui-Lin contain detailed accounts of the large trading vessels from Southeast Asia dating back to at least the 3rd century CE.

Traders used coins especially in foreign trade to export spices, muslin, cotton, pearls and precious stones to countries of the west and received the wine, olive oil, amphora and terracotta pots from there.

On the orders of Manuel I of Portugal, four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1497, continuing to Malindi on the eastern coast of Africa, from there to sail across the Indian Ocean to Calicut.

Ships constructed at Bombay in its heyday were said to be 'vastly superior to anything built anywhere else in the world'.The 1869 completion of the Suez Canal created a more direct route between Britain and India, furthering the importance of coastal cities like Mumbai.

[82] Following difficulty in obtaining spare parts from the Soviet Union, India also embarked upon a massive indigenous naval designing and production programme aimed at manufacturing destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and submarines.

[77] Rajesh Kadian (2006) holds that: "During the Kargil War (1999), the aggressive posture adopted by the navy played a role in convincing Islamabad and Washington that a larger conflict loomed unless Pakistan withdrew from the heights.".