Indigenous Philippine folk religions

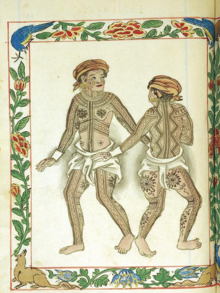

These Indigenous folk religions[1] where a set of local worship traditions are devoted to the anito or diwata (and their variables), terms which translate to Gods, spirits, and ancestors.

Accounts, both from Chinese and Spanish sources have explicitly noted the existence of indigenous religious writings.

In some sources, the Spanish claim that no such religious writings exist, while within the same chronicle, they record such books being burned on their own order.

[7] The profusion of different terms arises from the fact that these Indigenous religions mostly flourished in the pre-colonial period before the Philippines had become a single nation.

Third, Filipinos believed that events in the human world were influenced by the actions and interventions of these spirit beings.

Pag-anito (also called mag-anito or anitohan) is a séance, ritual where people communicate with the spirits of the dead or their ancestors.

[4][8][10] When Spanish missionaries arrived in the Philippines, the word "anito" came to be associated with the physical representations of spirits that featured prominently in paganito rituals.

[8][11] The belief in anito or ancestor worship is sometimes referred to as anitism in scholarly literature (Spanish: anitismo or anitería).

[2][4] Lesser deities in Filipino religions generally fit into three broad categories: nature spirits residing in the environment, such as a mountain or a tree; guardian spirits in charge of specific aspects of daily life such as hunting or fishing; and deified ancestors or tribal heroes.

[21] In many cases among various Filipino ethnic groups, spirits of the dead are traditionally venerated and deified in accordance to ancient belief systems originating from the Indigenous Philippine folk religions.

[23] Throughout various cultural phases in the archipelago, specific communities of people gradually developed or absorbed notable symbols in their belief systems.

Many of these symbols or emblems are deeply rooted in indigenous epics, poems, and pre-colonial beliefs of the natives.

Numerous types of shamans use different kinds of items in their work, such as talismans or charms known as agimat or anting-anting, curse deflectors such as buntot pagi, and sacred oil concoctions, among many other objects.

All social classes, including the shamans, respect and revere their deity statues (called larauan, bulul, manang, etc.

In cases where a crime was met by injustice as the instigator wasn't persecuted properly or was acquitted despite mounting evidences, the victims or their family and friends can ask aid from witches to bring justice by way of black magic, which differs per ethnic association.

In traditional beliefs outside of mainstream Filipino movie renditions, it is believed that black magic in cases of injustice does not affect the innocent.

They were either small roofless platforms or standing poles split at the tip (similar to a tiki torch).

Unfortunately, a majority of these places of worship (which includes items associated with these sites such as idol statues and ancient documents written in suyat scripts) were brutalized and destroyed by the Spanish colonialists between the 15th to 19th centuries, and were continued to be looted by American imperialists in the early 20th century.

Additionally, the lands used by the native people for worship were mockingly converted by the colonialists as foundation for their foreign churches and cemeteries.

Examples of indigenous places of worship that have survived colonialism are mostly natural sites such as mountains, gulfs, lakes, trees, boulders, and caves.

[53][56][61][62] In traditional dambana beliefs, all deities, beings sent by the supreme deity/deities, and ancestor spirits are collectively called anitos or diwata.

[64] It is adorned with statues home to anitos traditionally-called larauan, statues reserved for future burial practices modernly-called likha, scrolls or documents with suyat baybayin calligraphy,[65] and other objects sacred to dambana practices such as lambanog (distilled coconut wine), tuba (undistilled coconut wine), bulaklak or flowers (like sampaguita, santan, gumamela, tayabak, and native orchids), palay (unhusked rice), bigas (husked rice), shells, pearls, jewels, beads, native crafts such as banga (pottery),[66] native swords and bladed weapons (such as kampilan, dahong palay, bolo, and panabas), bodily accessories (like singsing or rings, kwintas or necklaces, and hikaw or earrings), war shields (such as kalasag), enchanted masks,[67] battle weapons used in pananandata or kali, charms called agimat or anting-anting,[68] curse deflectors such as buntot pagi, native garments and embroideries, food, and gold in the form of adornments (gold belts, necklace, wrist rings, and feet rings) and barter money (piloncitos and gold rings).

[69][70] Animal statues, notably native dogs, guard a dambana structure along with engravings and calligraphy portraying protections and the anitos.

The registry safeguards a variety of Philippine heritage elements, including oral literature, music, dances, ethnographic materials, and sacred grounds, among many others.