Interactionism (philosophy of mind)

[3] In the 20th century, its most significant defenders have been the noted philosopher of science Karl Popper and the neurophysiologist John Carew Eccles.

[4] Popper, in fact, divided reality into three "worlds"—the physical, the mental, and objective knowledge (outside the mind)—all of which interact,[5] and Eccles adopted this same "trialist" form of interactionism.

[6] Other notable recent philosophers to take an interactionist stance have been Richard Swinburne, John Foster, David Hodgson, and Wilfrid Sellars, in addition to the physicist Henry Stapp.

[10] The idea that causation necessarily depends on push-pull mechanisms (which would not be possible for a substance that did not occupy space) is also arguably based on obsolete conceptions of physics.

[2] One objection often posed to interactionism is the problem of causal interaction – how the two different substances the theory posits, the mental and the physical, can exert an impact on one another.

Princess Elisabeth questioned how a mental occurrence, such as intention, can cause a finger to move if immaterial things never come into direct contact with the physical world.

[11] Elizabeth of Bohemia's objection is part of the "pairing problem", a point raised by the philosopher Jaegwon Kim that Amy Kind also mentions in her book.

[3] On the other hand, Baruch Spinoza rejected Descartes' dualism and proposed that mind and matter were in fact properties of a single substance,[3] thereby prefiguring the modern perspective of neutral monism.

[10] Karl Popper and John Eccles, as well as the physicist Henry Stapp, have theorized that such indeterminacy may apply at the macroscopic scale.

[17] He acknowledges this is at odds with the interpretations of quantum mechanics held by most physicists, but notes, "There is some irony in the fact that philosophers reject interactionism on largely physical grounds (it is incompatible with physical theory), while physicists reject an interactionist interpretation of quantum mechanics on largely philosophical grounds (it is dualistic).

[7] There remains a literature in philosophy and science, albeit a much-contested one, that asserts evidence for emergence in various domains, which would undermine the principle of causal closure.

To imagine this argument, Amy Kind refers to a case from Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, where three snipers each fire a bullet into an Austrian Chancellor's heart.

However, J. J. C. Smart and Paul Churchland have argued that if physical phenomena fully determine behavioral events, then by Occam's razor a non-physical mind is unnecessary.

They exemplify the above with the discovery of relativity in physics, which was not the product of accepting Occam's razor but rather of rejecting it and asking the question of whether it could be that a deeper generalization, not required by the currently available data, was true and allowed for unexpected predictions.

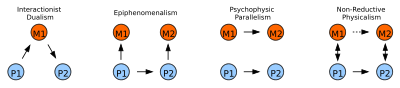

[19] While causal closure remains a key obstacle for interactionism, it is not relevant to all forms of dualism; epiphenomenalism and parallelism are unaffected as they do not posit that the mind affects the body.