Intestinal epithelium

To securely contain the contents of the intestinal lumen, the cells of the epithelial layer are joined together by tight junctions, thus forming a contiguous and relatively impermeable membrane.

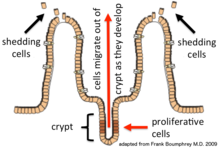

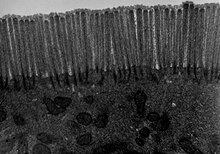

[5] In the small intestine, the mucosal layer is specially adapted to provide a large surface area in order to maximize the absorption of nutrients.

[16] These complexes, consisting of transmembrane adhesion proteins of the cadherin family, link adjacent cells together through their cytoskeletons.

[15] While previously thought to be static structures, tight junctions are now known to be dynamic and can change the size of the opening between cells and thereby adapt to the different states of development, physiologies and pathologies.

[15] The intestinal epithelium has a complex anatomical structure which facilitates motility and coordinated digestive, absorptive, immunological and neuroendocrine functions.

[21][22] Overlaying the brush border of the apical surface of the enterocytes is the glycocalyx, which is a loose network composed of the oligosaccharide side chains of integral membrane hydrolases and other enzymes essential for the digestion of proteins and carbohydrates.

[19] Also, the plasma membrane resistance and variable transmembrane conductance of the epithelial cells can also modulate paracellular pathway function.

It closely monitors its intracellular and extracellular environment, communicates messages to neighbouring cells and rapidly initiates active defensive and repair measures, if necessary.

[24] On the one hand, it acts as a barrier, preventing the entry of harmful substances such as foreign antigens, toxins and microorganisms.

[14][15] On the other hand, it acts as a selective filter which facilitates the uptake of dietary nutrients, electrolytes, water and various other beneficial substances from the intestinal lumen.

[15] When barrier integrity is lost, intestinal permeability increases and uncontrolled passage of harmful substances can occur.

This can lead to, depending on the genetic predisposition of the individual, the development of inflammation, infection, allergies, autoimmune diseases or cancer - within the intestine itself or other organs.

Loss of integrity of the intestinal epithelium plays a key pathogenic role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Breaches in this critical barrier (the intestinal epithelium) allow further infiltration of microbiota that, in turn, elicit further immune responses.

IBD is a multifactorial disease that is nonetheless driven in part by an exaggerated immune response to gut microbiota that causes defects in epithelial barrier function.

[28] Bile acids are normal components of the luminal contents of the gastrointestinal tract where they can act as physiologic detergents and regulators of intestinal epithelial homeostasis.