Introduction to general relativity

Experiments and observations show that Einstein's description of gravitation accounts for several effects that are unexplained by Newton's law, such as minute anomalies in the orbits of Mercury and other planets.

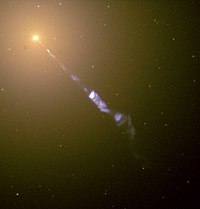

It provides the foundation for the current understanding of black holes, regions of space where the gravitational effect is strong enough that even light cannot escape.

Their strong gravity is thought to be responsible for the intense radiation emitted by certain types of astronomical objects (such as active galactic nuclei or microquasars).

In September 1905, Albert Einstein published his theory of special relativity, which reconciles Newton's laws of motion with electrodynamics (the interaction between objects with electric charge).

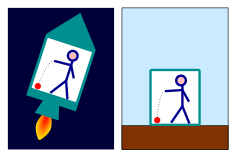

Einstein's master insight was that the constant, familiar pull of the Earth's gravitational field is fundamentally the same as these fictitious forces.

Nonetheless, he was able to make a number of novel, testable predictions that were based on his starting point for developing his new theory: the equivalence principle.

This is illustrated in the figure at left, which shows a light wave that is gradually red-shifted as it works its way upwards against the gravitational acceleration.

Quantitatively, his results were off by a factor of two; the correct derivation requires a more complete formulation of the theory of general relativity, not just the equivalence principle.

When it comes to explaining gravity near our own location on the Earth's surface, noting that our reference frame is not in free fall, so that fictitious forces are to be expected, provides a suitable explanation.

In a small environment such as a freely falling lift, this relative acceleration is minuscule, while for skydivers on opposite sides of the Earth, the effect is large.

For gravitational fields, the absence or presence of tidal forces determines whether or not the influence of gravity can be eliminated by choosing a freely falling reference frame.

[13][14] After he had realized the validity of this geometric analogy, it took Einstein a further three years to find the missing cornerstone of his theory: the equations describing how matter influences spacetime's curvature.

Instead, test particles move along lines called geodesics, which are "as straight as possible", that is, they follow the shortest path between starting and ending points, taking the curvature into consideration.

[18] For objects massive enough that their own gravitational influence cannot be neglected, the laws of motion are somewhat more complicated than for test particles, although it remains true that spacetime tells matter how to move.

Taken together, in general relativity it is mass, energy, momentum, pressure and tension that serve as sources of gravity: they are how matter tells spacetime how to curve.

More concretely, they are formulated using the concepts of Riemannian geometry, in which the geometric properties of a space (or a spacetime) are described by a quantity called a metric.

The metric encodes the information needed to compute the fundamental geometric notions of distance and angle in a curved space (or spacetime).

Newton's law of gravity was accepted because it accounted for the motion of planets and moons in the Solar System with considerable accuracy.

As the precision of experimental measurements gradually improved, some discrepancies with Newton's predictions were observed, and these were accounted for in the general theory of relativity.

The subsequent experimental confirmation of his other predictions, especially the first measurements of the deflection of light by the sun in 1919, catapulted Einstein to international stardom.

The geodetic and frame-dragging effects were both tested by the Gravity Probe B satellite experiment launched in 2004, with results confirming relativity to within 0.5% and 15%, respectively, as of December 2008.

In turn, tests of the system's accuracy (especially the very thorough measurements that are part of the definition of universal coordinated time) are testament to the validity of the relativistic predictions.

Even in cases where that object is not directly visible, the shape of a lensed image provides information about the mass distribution responsible for the light deflection.

[34] Gravitational waves, a direct consequence of Einstein's theory, are distortions of geometry that propagate at the speed of light, and can be thought of as ripples in spacetime.

Gravitational wave observations can be used to obtain information about compact objects such as neutron stars and black holes, and also to probe the state of the early universe fractions of a second after the Big Bang.

According to these models, our present universe emerged from an extremely dense high-temperature state – the Big Bang – roughly 14 billion years ago and has been expanding ever since.

Since the end of the 1990s, however, astronomical evidence indicating an accelerating expansion consistent with a cosmological constant – or, equivalently, with a particular and ubiquitous kind of dark energy – has steadily been accumulating.

[42] General relativity is very successful in providing a framework for accurate models which describe an impressive array of physical phenomena.

It has long been hoped that a theory of quantum gravity would also eliminate another problematic feature of general relativity: the presence of spacetime singularities.

These singularities are boundaries ("sharp edges") of spacetime at which geometry becomes ill-defined, with the consequence that general relativity itself loses its predictive power.