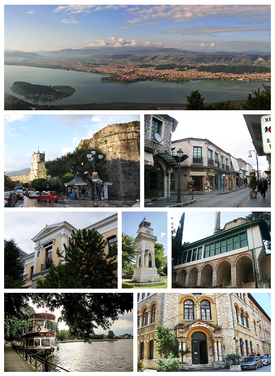

Ioannina

The city's foundation has traditionally been ascribed to the Byzantine Emperor Justinian in the 6th century AD, but modern archaeological research has uncovered evidence of Hellenistic settlements.

It became part of the Despotate of Epirus following the Fourth Crusade and many wealthy Byzantine families fled there following the 1204 sack of Constantinople, with the city experiencing great prosperity and considerable autonomy, despite the political turmoil.

The city's emblem consists of the portrait of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian crowned by a stylized depiction of the nearby ancient theater of Dodona.

The demotic form also corresponds to those in the neighboring languages (e.g., Albanian: Janina or Janinë, Aromanian: Ianina, Enina or Enãna, Macedonian: Јанина, Turkish: Yanya).

The first indications of human presence in Ioannina basin are dated back to the Paleolithic period (24,000 years ago) as testified by findings in the cavern of Kastritsa.

Despite the extensive destruction suffered in Molossia during the Roman conquest of 167 BC, settlement continued in the basin albeit no longer in an urban pattern.

[12] The exact time of Ioannina's foundation is unknown, but it is commonly identified with an unnamed new, "well-fortified" city, recorded by the historian Procopius as having been built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I for the inhabitants of ancient Euroia.

[15][16] It is not until 879 that the name Ioannina appears for the first time, in the acts of the Fourth Council of Constantinople, which refer to one Zacharias, Bishop of Ioannine, a suffragan of Naupaktos.

[18] In the treaty of partition of the Byzantine lands after the Fourth Crusade, Ioannina was promised to the Venetians, but in the event, it became part of the new state of Epirus, founded by Michael I Komnenos Doukas.

Despite frictions with local inhabitants who tried in 1232 to expel the refugees, the latter were eventually successfully settled and Ioannina gained in both population and economic and political importance.

[18][22][23] Following the assassination in 1318 of the last native ruler, Thomas I Komnenos Doukas, by his nephew Nicholas Orsini, the city refused to accept the latter and turned to the Byzantines for assistance.

On this occasion, Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos elevated the city to a metropolitan bishopric, and in 1319 issued a chrysobull conceding wide-ranging autonomy and various privileges and exemptions on its inhabitants.

Thomas proved a deeply unpopular ruler, but he nonetheless repelled successive attempts by Albanian chieftains including a surprise attack in 1379, whose failure the Ioannites attributed to intervention by their patron saint, Michael.

Despite the ongoing Ottoman expansion and the conflicts between Turks and Albanians in the vicinity of Ioannina, Esau managed to secure a period of peace for the city, especially following his second marriage to Shpata's daughter Irene in c. 1396.

Following Esau's death in 1411, the Ioannites invited the Count palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos, Carlo I Tocco, who had already been expanding his domains into Epirus for the last decade, as their new ruler.

By 1416 Carlo I Tocco had managed to capture Arta as well, thereby reuniting the core of the old Epirote realm, and received recognition from both the Ottomans and the Byzantine emperor.

[35] The Ottoman reprisals in the wake of the revolt included the confiscation of many timars previously granted to Christian sipahis; this began a wave of conversions to Islam by the local gentry, who became the so-called Tourkoyanniotes (Τoυρκογιαννιώτες).

The Maroutsaia also suffered after the fall of Venice and closed in 1797 to be reopened as the Kaplaneios School thanks to a benefaction from an Ioannite living in Russia, Zoes Kaplanes.

Psalidas established an important library of thousands of volumes in several languages and laboratories for the study of experimental physics and chemistry that aroused the interest and suspicion of Ali Pasha.

Born in Tepelenë, he maintained diplomatic relations with the most important European leaders of the time and his court became a point of attraction for many of those restless minds who would become major figures of the Greek Revolution (Georgios Karaiskakis, Odysseas Androutsos, Markos Botsaris and others).

During this time, however, Ali Pasha committed a number of atrocities against the Greek population of Ioannina, culminating in the sewing up of local women in sacks and drowning them in the nearby lake,[41] this period of his rule coincides with the greatest economic and intellectual prosperity of the city.

When the French scholar François Pouqueville visited the city during the early years of the 19th century, he counted 3,200 homes (2,000 Christian, 1,000 Muslim, 200 Jewish).

[8] The efforts of Ali Pasha to break away from the Sublime Porte alarmed the Ottoman government, and in 1820 (the year before the Greek War of Independence began) he was declared guilty of treason and Ioannina was besieged by Turkish troops.

Communities of people from Ioannina living abroad were active in financing the construction of most of the city's churches, schools and other elegant buildings of charitable establishments.

[44][45][46][47] The Greek population of the region authorized a committee to present to European governments their wish for union with Greece; as a result Dimitrios Chasiotis published a memorandum in Paris in 1879.

The monastery of St Panteleimon, where Ali Pasha spent his last days waiting for a pardon from the Sultan, is now a museum housing everyday artefacts and relics of his period.

At the south-eastern edge of the town on a rocky peninsula of Lake Pamvotis, the castle was the administrative heart of the Despotate of Epirus, and the Ottoman vilayet.

The municipal clock tower of Ioannina, designed by local architect Periklis Meliritos, was erected in 1905 to celebrate the Jubilee of sultan Abdul Hamid II.

It includes archaeological exhibits documenting the human habitation of Epirus from prehistoric times through the late Roman Period, with special emphasis placed on finds from the Dodona sanctuary.

A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed with the Greek-German Chamber, outlining the recovery plan for the region, a move that has been seen as a significant step in boosting technological development in Ioannina.