Iron in biology

[6][7][8][9][10] Examples of iron-containing proteins in higher organisms include hemoglobin, cytochrome (see high-valent iron), and catalase.

[1][17] A major component of this regulation is the protein transferrin, which binds iron ions absorbed from the duodenum and carries it in the blood to cells.

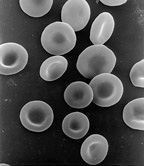

[21] Hemoglobin is an oxygen carrier that occurs in red blood cells and contributes their color, transporting oxygen in the arteries from the lungs to the muscles where it is transferred to myoglobin, which stores it until it is needed for the metabolic oxidation of glucose, generating energy.

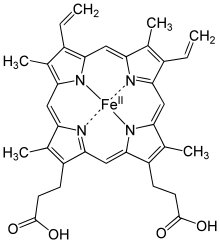

[5] In hemoglobin, the iron is in one of four heme groups and has six possible coordination sites; four are occupied by nitrogen atoms in a porphyrin ring, the fifth by an imidazole nitrogen in a histidine residue of one of the protein chains attached to the heme group, and the sixth is reserved for the oxygen molecule it can reversibly bind to.

[5] When hemoglobin is not attached to oxygen (and is then called deoxyhemoglobin), the Fe2+ ion at the center of the heme group (in the hydrophobic protein interior) is in a high-spin configuration.

This results in a movement of all the protein chains that leads to the other subunits of hemoglobin changing shape to a form with larger oxygen affinity.

[5] Here, the electron transfer takes place as the iron remains in low spin but changes between the +2 and +3 oxidation states.

Since the reduction potential of each step is slightly greater than the previous one, the energy is released step-by-step and can thus be stored in adenosine triphosphate.

[5] The ability of sea mussels to maintain their grip on rocks in the ocean is facilitated by their use of organometallic iron-based bonds in their protein-rich cuticles.

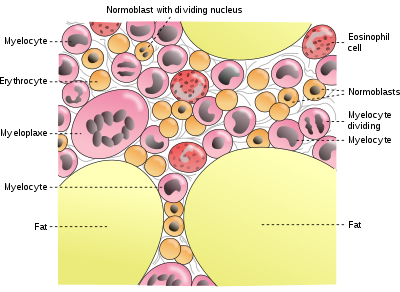

[24] Of this, about 2.5 g is contained in the hemoglobin needed to carry oxygen through the blood (around 0.5 mg of iron per mL of blood),[25] and most of the rest (approximately 2 grams in adult men, and somewhat less in women of childbearing age) is contained in ferritin complexes that are present in all cells, but most common in bone marrow, liver, and spleen.

The reserves of iron in industrialized countries tend to be lower in children and women of child-bearing age than in men and in the elderly.

Iron-deficient people will suffer or die from organ damage well before their cells run out of the iron needed for intracellular processes like electron transport.

If systemic iron overload is corrected, over time the hemosiderin is slowly resorbed by the macrophages.

For instance, enterocytes synthesize more Dcytb, DMT1 and ferroportin in response to iron deficiency anemia.

[29] Iron absorption from diet is enhanced in the presence of vitamin C and diminished by excess calcium, zinc, or manganese.

Recent discoveries demonstrate that hepcidin regulation of ferroportin is responsible for the syndrome of anemia of chronic disease.

Most of the iron in the body is hoarded and recycled by the reticuloendothelial system, which breaks down aged red blood cells.

In these diseases, the toxicity of iron starts overwhelming the body's ability to bind and store it.

[34][35] The higher order multifunctional glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) also acts as a transferrin receptor.

[36][37] Transferrin-bound ferric iron is recognized by these transferrin receptors, triggering a conformational change that causes endocytosis.

Iron then enters the cytoplasm from the endosome via importer DMT1 after being reduced to its ferrous state by a STEAP family reductase.

[38] Alternatively, iron can enter the cell directly via plasma membrane divalent cation importers such as DMT1 and ZIP14 (Zrt-Irt-like protein 14).

[39] Again, iron enters the cytoplasm in the ferrous state after being reduced in the extracellular space by a reductase such as STEAP2, STEAP3 (in red blood cells), Dcytb (in enterocytes) and SDR2.

[40] In this pool, iron is thought to be bound to low-mass compounds such as peptides, carboxylates and phosphates, although some might be in a free, hydrated form (aqua ions).

[48] The expression of hepcidin, which only occurs in certain cell types such as hepatocytes, is tightly controlled at the transcriptional level and it represents the link between cellular and systemic iron homeostasis due to hepcidin's role as "gatekeeper" of iron release from enterocytes into the rest of the body.

[38] Erythroblasts produce erythroferrone, a hormone which inhibits hepcidin and so increases the availability of iron needed for hemoglobin synthesis.

Iron plays an essential role in marine systems and can act as a limiting nutrient for planktonic activity.