Human iron metabolism

Thus, iron plays a vital role in the catalysis of enzymatic reactions that involve electron transfer (reduction and oxidation, redox).

Proteins can contain iron as part of different cofactors, such as iron–sulfur clusters (Fe-S) and heme groups, both of which are assembled in mitochondria.

Human cells require iron in order to obtain energy as ATP from a multi-step process known as cellular respiration, more specifically from oxidative phosphorylation at the mitochondrial cristae.

Heme groups are part of hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells that serves to transport oxygen from the lungs to other tissues.

Oxygen is transported from the lungs to the rest of the body bound to the heme group of hemoglobin in red blood cells.

[1][3] Typical intracellular labile iron concentrations in bacteria are 10-20 micromolar,[4] though they can be 10-fold higher in anaerobic environment,[5] where free radicals and reactive oxygen species are scarcer.

[6] Although this mechanism is an elegant response to short-term bacterial infection, it can cause problems when it goes on so long that the body is deprived of needed iron for red cell production.

In this case, iron withholding actually impairs health by preventing the manufacture of enough hemoglobin-containing red blood cells.

[7] Of this, about 2.5 g is contained in the hemoglobin needed to carry oxygen through the blood (around 0.5 mg of iron per mL of blood),[8] and most of the rest (approximately 2 grams in adult men, and somewhat less in women of childbearing age) is contained in ferritin complexes that are present in all cells, but most common in bone marrow, liver, and spleen.

The reserves of iron in industrialized countries tend to be lower in children and women of child-bearing age than in men and in the elderly.

Iron-deficient people will suffer or die from organ damage well before their cells run out of the iron needed for intracellular processes like electron transport.

[13] Iron absorption from diet is enhanced in the presence of vitamin C and diminished by excess calcium, zinc, or manganese.

Recent discoveries demonstrate that hepcidin regulation of ferroportin is responsible for the syndrome of anemia of chronic disease.

Most of the iron in the body is hoarded and recycled by the reticuloendothelial system, which breaks down aged red blood cells.

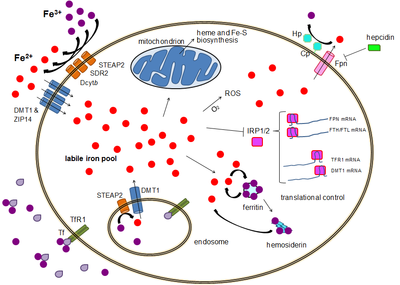

[19][20] Transferrin-bound ferric iron is recognized by these transferrin receptors, triggering a conformational change that causes endocytosis.

Iron then enters the cytoplasm from the endosome via importer DMT1 after being reduced to its ferrous state by a STEAP family reductase.

[21] Alternatively, iron can enter the cell directly via plasma membrane divalent cation importers such as DMT1 and ZIP14 (Zrt-Irt-like protein 14).

[22] Again, iron enters the cytoplasm in the ferrous state after being reduced in the extracellular space by a reductase such as STEAP2, STEAP3 (in red blood cells), Dcytb (in enterocytes) and SDR2.

[24] Malignant cells often exhibit a heightened demand for iron, fueling their transition towards a more invasive mesenchymal state.

This iron is necessary for the expression of mesenchymal genes, like those encoding transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), crucial for EMT.

Notably, iron’s unique ability to catalyze protein and DNA demethylation plays a vital role in this gene expression process.

As a result, various cytokines and growth factors trigger the upregulation of CD44, a surface molecule capable of internalizing iron bound to the hyaluronan complex.

This alternative pathway, relying on CD44-mediated endocytosis, becomes the dominant iron uptake mechanism compared to the traditional TfR1-dependent route.

[25] In this pool, iron is thought to be bound to low-mass compounds such as peptides, carboxylates and phosphates, although some might be in a free, hydrated form (aqua ions).

[21] Erythroblasts produce erythroferrone, a hormone which inhibits hepcidin and so increases the availability of iron needed for hemoglobin synthesis.

These causes can be grouped into several categories: The body is able to substantially reduce the amount of iron it absorbs across the mucosa.

Large amounts of free iron in the circulation will cause damage to critical cells in the liver, the heart and other metabolically active organs.

The type of acute toxicity from iron ingestion causes severe mucosal damage in the gastrointestinal tract, among other problems.

The exact mechanisms of most of the various forms of adult hemochromatosis, which make up most of the genetic iron overload disorders, remain unsolved.

- The transcytosis pathway (illustrated in the upper right segment of the image), where the complex “Fe 3+ -transferrin-transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1)” undergoes endocytosis and exocytosis from the luminal pole to the cerebral extracellular matrix (ECM) and interstitial fluid .

- The facilitated transporter pathway, where endothelial cells internalize the complex “Fe 3+ -transferrin-transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1)” in endosome, reduce ferric Fe 3+ ion to ferrous Fe 2+ ion by STEAP3 enzyme and then Fe 2+ ion crosses the endosomal membrane thanks to DMT1. Fe 2+ is then exported to the extracellular matrix (ECM) and interstitial fluid, via ferroportin coupled with ceruloplasmin.