Iranian architecture

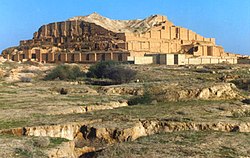

[4] Its virtues are "a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivaled in any other architecture".

[5] Traditional Persian architecture has maintained a continuity that, although temporarily distracted by internal political conflicts or foreign invasion, nonetheless has achieved an unmistakable style.

[4] Arthur Pope, a 20th-century scholar of Persian architecture, described it in these terms: "there are no trivial buildings; even garden pavilions have nobility and dignity, and the humblest caravanserais generally have charm.

"[6] According to scholars Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar, the guiding formative motif of Iranian architecture has been its cosmic symbolism "by which man is brought into communication and participation with the powers of heaven".

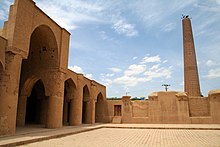

Heavy clays, readily available at various places throughout the plateau, have encouraged the development of the most primitive of all building techniques, molded mud, compressed as solidly as possible, and allowed to dry.

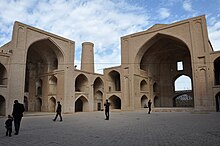

The columned porch, or talar, seen in the rock-cut tombs near Persepolis, reappear in Sassanid temples, and in late Islamic times it was used as the portico of a palace or mosque, and adapted even to the architecture of roadside tea-houses.

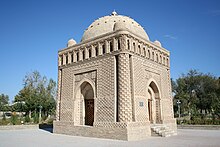

The post-Islamic architecture of Iran in turn, draws ideas from its pre-Islamic predecessor, and has geometrical and repetitive forms, as well as surfaces that are richly decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy.

Examples of this style are Ghal'eh Dokhtar, the royal compounds at Nysa, Anahita Temple, Khorheh, Hatra, the Ctesiphon vault of Kasra, Bishapur, and the Palace of Ardashir in Ardeshir Khwarreh (Firouzabad).

[22][23] During the 8th and 9th centuries, the power and unity of the Abbasid Caliphate allowed architectural features and innovations from its heartlands to spread quickly to other areas of the Islamic world under its influence, including Iran.

[23] The Sasanian tradition of building caravanserais along trade routes also continued, with the remains of one such structure in southern Turkmenistan attesting to the presence of a central courtyard surrounded by arcaded galleries with domed roofs.

[38][35] Turkic peoples began moving west across Central Asia and towards the Middle East from the 8th century onward, eventually converting to Islam and becoming major forces in the region.

[39] While the apogee of the Great Seljuks was short-lived, it represents a major benchmark in the history of Islamic art and architecture in Iran and Central Asia, inaugurating an expansion of patronage and of artistic forms.

[43] Nonetheless, compared to pre-Seljuk Iran, a larger volume of surviving monuments and artifacts from the Seljuk period has allowed scholars to study the arts of this era in greater depth.

A general tradition of architecture was thus shared across most of the eastern Islamic world (Iran, Central Asia, and parts of the northern Indian subcontinent) throughout the Seljuk period and its decline, from the 11th to 13th centuries.

[35] Lodging places (khān, or caravanserai) for travellers and their animals, generally displayed utilitarian rather than ornamental architecture, with rubble masonry, strong fortifications, and minimal comfort.

In Iran and Central Asia, the Khwarazm-Shahs, formerly vassals of the Seljuks and Qara Khitai, took advantage of this to expand their power and form the Khwarazmian Empire, occupying much of the region and conquering the Ghurids in the early 13th century, only to fall soon after to the Mongol invasions.

[57] The most impressive monument to survive from this period is the Soltaniyeh Mausoleum built for Sultan Uljaytu (r. 1304–1317), a massive dome supported on a multi-level octagonal structure with internal and external galleries.

Only the domed building remains today, missing much of its original turquoise tile decoration, but it was once the centerpiece of a larger religious complex including a mosque, a hospital, and living areas.

[57] Timur's own monuments are distinguished by their size; notably, the Bibi Khanum Mosque and the Gur-i Amir Mausoleum, both in Samarkand, and his imposing but now-ruined Ak-Saray Palace at Shahr-i Sabz.

[62] Timur's successors built on a somewhat smaller scale, but under the patronage of Gawhar Shad, the wife of his son Shah Rukh (r. 1405–1447), Timurid architecture attained the height of sophistication during the first half of the 15th century.

The international Timurid style was eventually integrated into the visual culture of the rising Ottoman Empire in the west,[64] while to the east it was transmitted to the Indian subcontinent by the Mughals, who were descended from Timur.

It has an unusual T-shaped layout around a central dome, not unlike the Ottoman Green Mosque in Bursa, and is decorated with a revetment of very high-quality tilework in six colours, including a deep blue.

It includes a sprawling Grand Bazaar, lined with caravanserais, which opens via a monumental portal onto a vast, rectangular public square, the Maidan-i Shah or Naqsh-e Jahan, laid out between 1590 and 1602.

Muhammad Karim Khan Zand, the dynasty's founder, created a grand square and built a new set of monuments, in a way similar to the Safavid construction projects in Isfahan, though on a smaller scale.

[67] In Shiraz (which came under Qajar rule in 1794), the Mosque of Nasir al-Mulk (1876–1888) has a traditional layout but exemplifies a new style of decorative tiles, painted in overglaze with images of flower bouquets in predominantly blue, pink, yellow, violet and green colors, sometimes on a white background.

Qajar monarchs, including Fath Ali Shah, commissioned works that deliberately referenced Safavid and ancient Sasanian architecture, hoping to appropriate their symbolism of kingship and empire.

[67][72] He also remodelled Tehran, demolishing the dense urban fabric in parts of the old city, as well as its historic walls, and replacing them with boulevards and open squares inspired by what he saw in his visits to Europe.

[77] The renaissance in Persian mosque and dome building came during the Safavid dynasty, when Shah Abbas, in 1598, initiated the reconstruction of Isfahan, with the Naqsh-e Jahan Square as the centerpiece of his new capital.

[80] The extensive inscription bands of calligraphy and arabesque on most of the major buildings where carefully planned and executed by Ali Reza Abbasi, who was appointed head of the royal library and Master calligrapher at the Shah's court in 1598,[81] while Shaykh Bahai oversaw the construction projects.

Its founders included Vartan Avanessian, Abass Azhdari, Naser Badi, Abdelhamid Eshraq, Manuchehr Khorsandi, Iraj Moshiri, Ali Sadeq, and Keyghobad Zafar.