Istria

[1][2] This smallest portion of Istria consists of the comunes of Muggia/Milje and San Dorligo della Valle/Dolina with Santa Croce (Trieste) lying farthest to the north.

The ancient region of Histria extended over a much wider area, including the whole Karst Plateau with the southern edges of the Vipava Valley/Vipacco Valley, the southwestern portions of modern Inner Carniola with Postojna/Postumia and Ilirska Bistrica/Bisterza, and the Italian Province of Trieste, but not the Liburnian coast which was already part of Illyricum.

[7] The name is derived from the Histri (Ancient Greek: Ἱστρών έθνος) tribes, which Strabo refers to as living in the region and who are credited as being the builders of the hillfort settlements (castellieri).

Earlier influence of the Iapodes was attested there, while at some time between the 4th and 1st century BC the Liburnians extended their territory and it became a part of Liburnia.

Petar, erected in the 5th century (with a baptistery added later), which reportedly served the Arian eastern Goths ruling Istria.

[14][15] Pope Gregory I in 600 wrote to bishop of Salona Maximus in which he expresses concern about arrival of the Slavs, "Et quidem de Sclavorum gente, quae vobis valde imminet, et affligor vehementer et conturbor.

[19][20] By 642 the Slavs were settled in the peninsula, as indicated by the mission of an abbot Martin, sent by Pope John IV to rescue captives held by the pagans in Istria and Dalmatia.

In 804, the Placitum of Riziano was held in the Parish of Rižan (Latin: Risanum), which was a meeting between the representatives of Istrian towns and castles and the deputies of Charlemagne and his son Pepin.

The medieval Croatian kingdom held only the far eastern part of Istria (the border was near the river Raša), but they lost it to the Holy Roman Empire in the late 11th century.

Under Pietro II Candiano, who was Doge of Venice between 932 and 939, Istrian cities signed an act of devotion to the Venetian rule.

[22] The fleet visited all the main Istrian and Dalmatian cities, whose citizens, exhausted by the wars between the Croatian king Svetislav and his brother Cresimir, swore an oath of fidelity to Venice.

[23] During the 13th century, the Patriarchate's rule weakened and the towns kept surrendering to Venice – Poreč in 1267, Umag in 1269, Novigrad in 1270, Sveti Lovreč in 1271, Motovun in 1278, Kopar in 1279, and Piran and Rovinj in 1283.

[23] The wealthier coastal towns cultivated increasingly strong economic relationships with Venice and by 1348 were eventually incorporated into its territory, while their inland counterparts fell under the sway of the weaker Patriarchate of Aquileia, which became part of the Habsburg Empire in 1374.

A copy of the map inscribed in stone can now be seen in the Pietro Coppo Park in the center of the town of Izola in southwestern Slovenia.

Napoleon combined Istira, Carniola, western Carinthia, Gorica (Gorizia), Trieste and parts of Croatia, Dalmatia, and Dubrovnik to form the Illyrian Provinces.

This kingdom was broken up in 1849, after which Istria formed part of Austrian Littoral, also known as the "Küstenland", which also included the city of Trieste and the Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca until 1918.

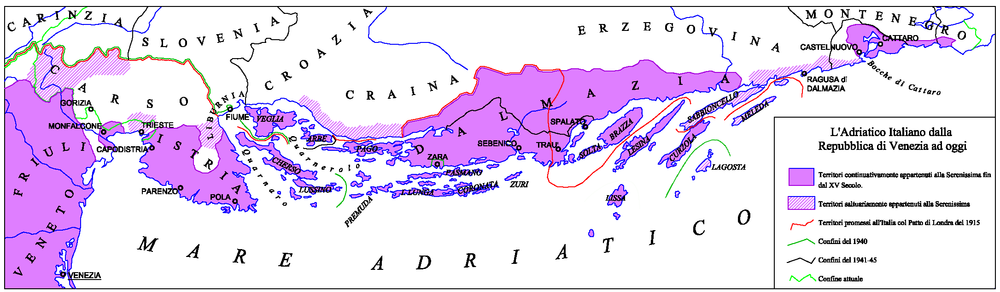

[30] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

[32] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[33] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.Although a member of the Central Powers, Italy remained neutral at the start of WWI, and soon launched secret negotiations with the Triple Entente, bargaining to participate in the war on its side, in exchange for significant territorial gains.

After the German withdrawal in 1945, Yugoslav partisans gained the upper hand and began a violent purge of real or suspected opponents in an "orgy of revenge".

[36] After the end of World War II, Istria was ceded to Yugoslavia, except for a small part in the northwest corner that formed Zone B of the provisionally independent Free Territory of Trieste; Zone B was under Yugoslav administration and after the de facto dissolution of the Free Territory in 1954 it was also incorporated into Yugoslavia.

[40] Most of them left in the immediate aftermath of the signing of the Paris Peace Treaty on February 10, 1947 which granted Pula and the greater part of Istria to Yugoslavia.

Since Croatia's first multi-party elections in 1990, the Istrian regionalist party Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS-DDI, Istarski demokratski sabor or Dieta democratica istriana) has consistently received a majority of the vote and maintained through the 1990s a position often contrary to the government in Zagreb, led by the then nationalistic party Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ, Hrvatska demokratska zajednica), with regards to decentralization in Croatia and certain facets of regional autonomy.

Since Slovenia's accession to the European Union and the Schengen Area, customs and immigration checks have been abolished at the Italian-Slovenian border.

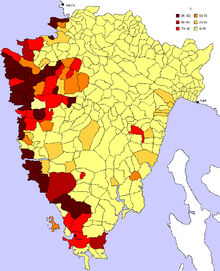

Under Austrian rule in the 19th century it included a large population of Italians, Croats, and Slovenes as well as some Istro-Romanians, Serbs,[42] and Montenegrins; however, official statistics in those times did not show those nationalities as they do today.

[51] With its strategic position at the southern tip of the peninsula and good harbor Pula was the primary base of the Austrian Navy.

A limited tension with the Austrian state did not in fact stop the rise of the use of the Italian language, in the second part of the 19th century, when the population of predominantly Italian-speaking towns in Istria had a significant rise: in the part of Istria that eventually became part of Croatia, the first Austrian census from 1846 found 34 thousand Italian speakers, alongside 120 thousand Croatian speakers (in the Austrian censuses, the ethnic composition of the population was not surveyed, only the main "language of use" of a person).

It can also refer to Istrian Croats who adopted the veneer of Italian culture as they moved from rural to urban areas, or from the farms into the bourgeoisie.

[58] Traditional dishes of Italian origin also include gnocchi (njoki), risotto (rižot), focaccia (pogača), polenta (palenta), and brudet.

[61] Under the name jota, it is typical and especially popular in Trieste and its province (where it is considered to be the prime example of Triestine food), in the Istrian peninsula, in the province of Gorizia, in the whole Slovenian Littoral, in the Rijeka area, and in Friuli, especially in some of its peripheral areas (the highland region of Carnia, the Torre and Natisone river valleys, or Slavia Veneta).