James McNeill Whistler

[9] Their fortunes improved considerably in 1839 when his father became chief engineer for the Boston & Albany Railroad,[13] and the family built a mansion in Springfield, Massachusetts, where the Wood Museum of History now stands.

[11] The young artist followed the traditional curriculum of drawing from plaster casts and occasional live models, revelled in the atmosphere of art talk with older peers, and pleased his parents with a first-class mark in anatomy.

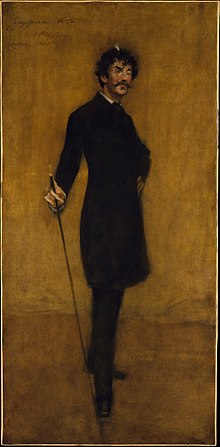

His cousin reported that Whistler at that time was "slight, with a pensive, delicate face, shaded by soft brown curls ... he had a somewhat foreign appearance and manner, which, aided by natural abilities, made him very charming, even at that age.

[23] However, it became clear that a career in religion did not suit him, so he applied to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where his father had taught drawing and other relatives had attended.

[22] While letters from home reported his mother's efforts at economy, Whistler spent freely, sold little or nothing in his first year in Paris, and was in steady debt.

Through him, Whistler was introduced to the circle of Gustave Courbet, which included Carolus-Duran (later the teacher of John Singer Sargent), Alphonse Legros, and Édouard Manet.

A critic wrote, "[despite] a recklessly bold manner and sketchiness of the wildest and roughest kind, [it has] a genuine feeling for colour and a splendid power of composition and design, which evince a just appreciation of nature very rare amongst artists.

[38] This painting also demonstrated Whistler's ongoing work pattern, especially with portraits: a quick start, major adjustments, a period of neglect, then a final flurry to the finish.

Countering criticism by traditionalists, Whistler's supporters insisted that the painting was "an apparition with a spiritual content" and that it epitomized his theory that art should be concerned essentially with the arrangement of colors in harmony, not with a literal portrayal of the natural world.

[44] In January 1864, Whistler's very religious and very proper mother arrived in London, upsetting her son's bohemian existence and temporarily exacerbating family tensions.

[51] His good friend Fantin-Latour, growing more reactionary in his opinions, especially in his negativity concerning the emerging Impressionist school, found Whistler's new works surprising and confounding.

The deceptively simple design is in fact a balancing act of differing shapes, particularly the rectangles of curtain, picture on the wall, and floor which stabilize the curve of her face, dress, and chair.

After the initial shock of her moving in with her son, she aided him considerably by stabilizing his behavior somewhat, tending to his domestic needs, and providing an aura of conservative respectability that helped win over patrons.

"[62] Martha Tedeschi writes: Whistler's Mother, Wood's American Gothic, Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa and Edvard Munch's The Scream have all achieved something that most paintings—regardless of their art historical importance, beauty, or monetary value—have not: they communicate a specific meaning almost immediately to almost every viewer.

[63]Other important portraits by Whistler include those of Thomas Carlyle (historian, 1873), Maud Franklin (his mistress, 1876), Cicely Alexander (daughter of a London banker, 1873), Lady Meux (socialite, 1882), and Théodore Duret (critic, 1884).

William Merritt Chase complained of his sitting for a portrait by Whistler, "He proved to be a veritable tyrant, painting every day into the twilight, while my limbs ached with weariness and my head swam dizzily.

[67] Whistler's approach to portraiture in his late maturity was described by one of his sitters, Arthur J. Eddy, who posed for the artist in 1894: He worked with great rapidity and long hours, but he used his colours thin and covered the canvas with innumerable coats of paint.

Some of the lithographs are of figures slightly draped; two or three of the very finest are of Thames subjects—including a "nocturne" at Limehouse; while others depict the Faubourg Saint-Germain in Paris, and Georgian churches in Soho and Bloomsbury in London.

The case came to trial the following year after delays caused by Ruskin's bouts of mental illness, while Whistler's financial condition continued to deteriorate.

He eagerly accepted the assignment, and arrived in the city with girlfriend Maud Franklin, taking rooms in a dilapidated palazzo they shared with other artists, including John Singer Sargent.

Though still struggling financially, he was heartened by the attention and admiration he received from the younger generation of English and American painters who made him their idol and eagerly adopted the title "pupil of Whistler".

[99]Whistler, however, thought himself mocked by Oscar Wilde, and from then on, public sparring ensued leading to a total breakdown of their friendship, precipitated by a report written by Herbert Vivian.

[113] Around this time, in addition to portraiture, Whistler experimented with early colour photography and with lithography, creating a series featuring London architecture and the human figure, mostly female nudes.

Canfield owned a number of fashionable gambling houses in New York and Rhode Island, including Saratoga Springs and Newport, and was also a man of culture with refined tastes in art.

He owned early American and Chippendale furniture, tapestries, Chinese porcelain and Barye bronzes, and possessed the second-largest and most important Whistler collection in the world prior to his death in 1914.

[121] A few months before his own death, Canfield sold his collection of etchings, lithographs, drawings and paintings by Whistler to the American art dealer Roland F. Knoedler for $300,000.

She was the widow of his friend E. W. Godwin, the architect who had designed Whistler's White House, and the daughter of the sculptor John Birnie Philip[141] and his wife Frances Black.

[143] Whistler was inspired by and incorporated many sources in his art, including the work of Rembrandt, Velázquez, and ancient Greek sculpture to develop his own highly influential and individual style.

His Tonalism had a profound effect on many American artists, including John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase, Henry Salem Hubbell, Willis Seaver Adams (whom he befriended in Venice) and Arthur Frank Mathews, whom Whistler met in Paris in the late 1890s and who took Whistler's Tonalism to San Francisco, spawning a broad use of that technique among turn-of-the-century California artists.

[citation needed] Novelist Henry James "had become well enough acquainted with Whistler to base several fictional characters on the 'queer little Londonized Southerner,' most notably in Roderick Hudson and The Tragic Muse".

Honored on Issue of 1940