Project Y

Oppenheimer then reorganized the laboratory and orchestrated an all-out and ultimately successful effort on an alternative design proposed by John von Neumann, an implosion-type nuclear weapon, which was called Fat Man.

[8] Progress was slow in the United States, but in Britain, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, two refugee physicists from Germany at the University of Birmingham, examined the theoretical issues involved in developing, producing and using atomic bombs.

They considered what would happen to a sphere of pure uranium-235, and found that not only could a chain reaction occur, but it might require as little as 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of uranium-235 to unleash the energy of hundreds of tons of TNT.

[12] There was still little urgency in the United States, which unlike Britain was not yet engaged in World War II, so Oliphant flew there in late August 1941,[13] and spoke to American scientists including his friend Ernest Lawrence at the University of California.

He not only managed to convince them that an atomic bomb was feasible, but inspired Lawrence to convert his 37-inch (94 cm) cyclotron into a giant mass spectrometer for isotope separation,[14] a technique Oliphant had pioneered in 1934.

[15] In turn, Lawrence brought in his friend and colleague Robert Oppenheimer to double-check the physics of the MAUD Committee report, which was discussed at a meeting at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, on 21 October 1941.

[17][18] He delegated bomb design and the making of fast neutron calculations—the key to calculations of critical mass and weapon detonation—to Gregory Breit, who was given the title of "Co-ordinator of Rapid Rupture", and Oppenheimer as an assistant.

[22] To review this work and the general theory of fission reactions, Oppenheimer and Fermi convened meetings at the University of Chicago in June and at the University of California in Berkeley, in July with theoretical physicists Hans Bethe, John Van Vleck, Edward Teller, Emil Konopinski, Robert Serber, Stan Frankel, and Eldred C. Nelson, the latter three former students of Oppenheimer, and experimental physicists Emilio Segrè, Felix Bloch, Franco Rasetti, John Manley, and Edwin McMillan.

[25] They also explored designs involving spheroids, a primitive form of "implosion" suggested by Richard C. Tolman, and the possibility of autocatalytic methods, which would increase the efficiency of the bomb as it exploded.

[33][37] Groves subsequently had Oppenheimer come to Washington, D.C., where the matter was discussed with Vannevar Bush, the director of the OSRD, and James B. Conant, the chairman of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC).

[44] The climate was mild, there were air and rail connections to Albuquerque, it was sufficiently distant from the West Coast of the United States for a Japanese attack not to be an issue, and the population density was low.

Oppenheimer was impressed by and expressed a strong preference for the site, citing its natural beauty and views of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, which, he hoped, would inspire those who would work on the project.

[49] Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard granted use of some 45,100 acres (18,300 ha) of United States Forest Service land to the War Department "for so long as the military necessity continues".

[98] The laboratory was organized into five divisions: Administration (A), Theoretical (T) under Bethe, Experimental Physics (P) under Bacher, Chemistry and Metallurgy (CM) under Kennedy, and Ordnance and Engineering (E) under Parsons.

[117] To staff the division, Tolman, who acted as a coordinator of the gun development effort, brought in John Streib, Charles Critchfield and Seth Neddermeyer from the National Bureau of Standards.

The first two tubes arrived at Los Alamos on 10 March 1944, and test firing began at the Anchor Ranch under the direction of Thomas H. Olmstead, who had experience in such work at the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia.

[122] Testing of Silverplate Boeing B-29 Superfortress aircraft with Thin Man bomb shapes was carried out at Muroc Army Air Field in March and June 1944.

Segrè and his group of young physicists set up their experiment in an old Forest Service log cabin in Pajarito Canyon, about 14 miles (23 km) from the Technical Area, in order to minimize background radiation emanating for other research at the Los Alamos Laboratory.

In July 1943, Oppenheimer wrote to John von Neumann, asking for his help, and suggesting that he visit Los Alamos where he could get "a better idea of this somewhat Buck Rogers project".

A meeting of the Governing Board on 23 September resolved to approach George Kistiakowsky, a renowned expert on explosives then working for OSRD, to join the Los Alamos Laboratory.

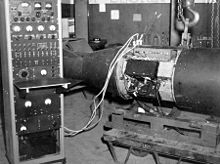

[160] To study the behavior of converging shock waves, Robert Serber devised the RaLa Experiment, which used the short-lived radioisotope lanthanum-140, a potent source of gamma radiation.

This was not immediately followed up, because tritium was hard to obtain, and there were hopes that deuterium could be easily ignited by a fission bomb, but the cross sections of T-D and D-D were measured by Manley's group in Chicago and Holloway's at Purdue.

Teller gave an outline of his "Classic Super" concept, and Nicholas Metropolis and Anthony L. Turkevich presented the results of calculations that had been made concerning thermonuclear reactions.

[210] Bainbridge worked with Captain Samuel P. Davalos on the construction of the Trinity Base Camp and its facilities, which included barracks, warehouses, workshops, an explosive magazine and a commissary.

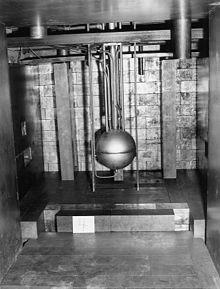

[211] Groves did not relish the prospect of explaining the loss of a billion dollars worth of plutonium to a Senate committee, so a cylindrical containment vessel codenamed "Jumbo" was constructed to recover the active material in the event of a failure.

A wooden test platform was erected 800 yards (730 m) from Ground Zero and piled with 108 short tons (98 t) of TNT spiked with nuclear fission products in the form of an irradiated uranium slug from the Hanford Site, which was dissolved and poured into tubing inside the explosive.

[214][215] For the actual test, the device, nicknamed "the gadget", was hoisted to the top of a 100-foot (30 m) steel tower, as detonation at that height would give a better indication of how the weapon would behave when dropped from a bomber.

[228] In the meantime, a series of twelve combat missions were flown between 20 and 29 July against targets in Japan using high-explosive pumpkin bombs, versions of the Fat Man with the explosives, but not the fissile core.

[260] After the war ended on 14 August 1945, Oppenheimer informed Groves of his intention to resign as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, but agreed to remain until a suitable replacement could be found.

Eric Jette became responsible for Chemistry and Metallurgy, John H. Manley for Physics, George Placzek for Theory, Max Roy for Explosives, and Roger Wagner for Ordnance.