Jacobins

Initially founded in 1789 by anti-royalist deputies from Brittany, the club grew into a nationwide republican movement with a membership estimated at a half million or more.

[3] In 1792–93, the Girondins were more prominent in leading France when they declared war on Austria and on Prussia, overthrew King Louis XVI, and set up the French First Republic.

[citation needed] In modern France, the term Jacobin generally denotes a position of more equal formal rights, centralization, and moderate authoritarianism.

The club was re-founded in November 1789 as the Société de la Révolution, inspired in part by a letter sent from the Revolution Society of London to the Assembly congratulating the French on regaining their liberty.

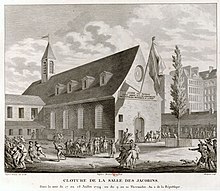

[9][10][11] To accommodate growing membership, the group rented for its meetings the refectory of the Dominican monastery of the “Jacobins” in the Rue Saint-Honoré, adjacent to the seat of the Assembly.

[10][11] They changed their name to Société des amis de la Constitution in late January, though by this time, their opponents had already concisely dubbed them "Jacobins", a nickname originally given to French Dominicans because their first house in Paris was in the Rue Saint-Jacques.

All citizens were allowed to enter, and even foreigners were welcomed: the English writer Arthur Young joined the club in this manner on 18 January 1790.

Jacobin Club meetings soon became a place for radical and rousing oratory that pushed for republicanism, widespread education, universal suffrage, separation of church and state, and other reforms.

[12] On 8 February 1790, the society became formally constituted on this broader basis by the adoption of the rules drawn up by Barnave, which were issued with the signature of the duc d'Aiguillon, the president.

By 10 August 1790 there were already one hundred and fifty-two affiliated clubs; the attempts at counter-revolution led to a great increase of their number in the spring of 1791, and by the close of the year the Jacobins had a network of branches all over France.

[13] As far as the central society in Paris was concerned, it was composed almost entirely of professional men (such as the lawyer Robespierre) and well-to-do bourgeoisie (like the brewer Santerre).

The club further included people like "père" Michel Gérard, a peasant proprietor from Tuel-en-Montgermont, in Brittany, whose rough common sense was admired as the oracle of popular wisdom, and whose countryman's waistcoat and plaited hair were later on to become the model for the Jacobin fashion.

The Jacobins finally rid itself of Feuillants in its midst; the number of clubs increased considerably, convening became a nationwide fad.

[14] From then on, a polarization process started among the members of the Jacobin Club, between a group around Robespierre – after September 1792 called 'Montagnards' or 'Montagne', in English 'the Mountain' – and the Girondins.

In the newly elected National Convention, governing France as of 21 September 1792, Maximilien Robespierre made his comeback in the center of French power.

[17] Together with his 25-year-old protégé Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, Marat, Danton and other associates they took places on the left side on the highest seats of the session room: therefore that group around and led by Robespierre was called The Mountain (French: la Montagne, les Montagnards).

[32] Several deposed Girondin-Jacobin Convention deputies, among them Jean-Marie Roland, Brissot, Pétion, Louvet, Buzot and Guadet, left Paris to help organize revolts in more than 60 of the 83 departments against the politicians and Parisians, mainly Montagnards, that had seized power over the Republic.

[28] Meanwhile, the Montagnard-dominated government resorted also to harsh measures to repress what they considered counter-revolution, conspiracy[28][20] and "enemies of freedom" in the provinces outside Paris, resulting in 17,000 death sentences between September 1793 and July 1794 in all of France.

[33][34] In late June 1794, three colleagues on the Committee of Public Prosperity/Safety – Billaud-Varenne, Collot d'Herbois and Carnot – called Robespierre a dictator.

[28] Probably because of the high level of repressive violence – but also to discredit Robespierre and associates as solely responsible for it[36] – historians have taken up the habit to roughly label the period June 1793–July 1794 as 'Reign of Terror'.

[43] The Committee of General Security decided to close the Jacobins' meeting hall late that night, resulting in it being padlocked at four in the morning.

[44] The next meeting day, 22 Brumaire (12 November 1794), without debate the National Convention passed a decree permanently closing the Jacobin Club by a nearly unanimous vote.

It published a newspaper called the Journal des Libres, proclaimed the apotheosis of Robespierre and Babeuf, and attacked the Directory as a royauté pentarchique.

The suspicions of the government were aroused; it had to change its meeting-place from the Tuileries to the church of the Jacobins (Temple of Peace) in the Rue du Bac, and in August it was suppressed, after barely a month's existence.

[52] Ultimately, the Jacobins were to control several key political bodies, in particular the Committee of Public Safety and, through it, the National Convention, which was not only a legislature but also took upon itself executive and judicial functions.

"[57] The ultimate political vehicle for the Jacobin movement was the Reign of Terror overseen by the Committee of Public Safety, who were given executive powers to purify and unify the Republic.

[59] Georges Valois, founder of the first non-Italian fascist party Faisceau,[60] claimed the roots of fascism stemmed from the Jacobin movement.

[66][67] The undercurrent of radical and populist tendencies espoused and enacted by the Jacobins would create a complete cultural and societal shock within the traditional and conservative governments of Europe, leading to new political ideas of society emerging.

[69][70] Jacobin populism and complete structural destruction of the old order led to an increasingly revolutionary spirit throughout Europe and such changes would contribute to new political foundations.

[74] They advocated deliberate government-organized religion as a substitute for both the rule of law and a replacement of mob violence as inheritors of a war that at the time of their rise to power threatened the very existence of the Revolution.