Jacques Pierre Brissot

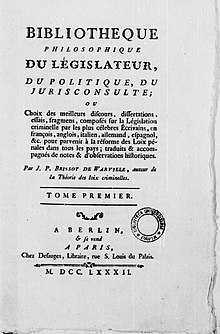

His initial literary endeavors, including Théorie des lois criminelles (1781) and Bibliothèque philosophique du législateur (1782), delved into the philosophy of law, demonstrating a profound influence of the ethical principles championed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

[11] DuPeyrou, a Suriname native who relocated to Neuchâtel in 1747, had maintained a close relationship with Rousseau, providing financial support and overseeing the publication of his complete works.

Brissot visited London where he got engaged in establishing an Academy of Arts and Sciences; he lived at Newman Street with his wife and younger brother.

In the preface of Théorie des lois criminelles, a plea for penal reform, Brissot explains that he submitted an outline of the book to Voltaire and quotes his answer from 13 April 1778.

After gaining release, Brissot returned to pamphleteering, most notably his 1785 open letter to emperor Joseph II of Austria, Seconde lettre d'un défenseur du peuple a l'Empereur Joseph II, sur son règlement concernant, et principalement sur la révolte des Valaques, which supported the right of subjects to revolt against the misrule of a monarch (in Bulgaria).

He considered Saint-Georges, a "man of color", the ideal person to contact his fellow abolitionists in London and ask their advice about Brissot's plans for Les Amis des Noirs (Friends of the Blacks) modeled on the English Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

It is supposed Saint Georges delivered Brissot's request to translate the publications of the abolitionists MPs William Wilberforce, John Wilkes, and Reverend Thomas Clarkson into French.

He also met with members of the constitutional convention in Philadelphia to find out what he could about the domestic debt of the United States and researching investment opportunities in Scioto Company.

In 1791, Brissot along with Marquis de Condorcet, Thomas Paine, and Étienne Dumont created a newspaper promoting republicanism titled Le Républicain.

Brissot was a key figure in the declaration of war against Leopold II, the Habsburg monarchy, the Dutch Republic, and the Kingdom of Great Britain on 1 February 1793.

[46] On 27 April, as part of his speech responding to the accusations by Brissot and Guadet against him, he threatened to leave the Jacobins, claiming he preferred to continue his mission as an ordinary citizen.

On Sunday morning 2 September the members of the Commune, gathering in the town hall to proceed the election of deputies to the National Convention, decided to maintain their seats and have Rolland and Brissot arrested.

[6] On 24 October 1792, Brissot published another pamphlet,[56] in which he declared the need for a coup against anarchists and the decentralized, populist element of the French Revolution, going so far as to demand the abolition of the Paris Commune.

Robespierre, who was not elected, was pessimistic about the prospects of parliamentary action and told the Jacobins that it was necessary to raise an army of Sans-culottes to defend Paris and arrest infidel deputies, naming and accusing Brissot, Isnard, Vergniaud, Guadet and Gensonné.

[62] Brissot was condemned and then escaped from Paris, going to Normandy and Brittany, where he and other Girondists, such as Pétion, Gaudet, Barbaroux, Louvet, Buzot, and Lanjuinais, had planned to organize Counter-Revolutionary Vendée Uprising.

Passing through his hometown Chartres on his way to the city of Caen, the centre of anti-revolutionary forces in Normandy, he was caught travelling with false papers on 10 June and taken back to Paris.

[77] Robespierre and Marat were among those who accused Brissot of various kinds of counterrevolutionary activity, such as, Orléanism, "federalism", being in the pay of Great Britain, having failed to vote for the immediate death of the former king, and having been a collaborator with General Dumouriez, widely considered a traitor following his April 5 defection to the Austrians.

[79] The accusations were led by Jean-Paul Marat, Camille Desmoulins, Maximilien Robespierre, and above all the notorious scandal-monger, extortioner, and perjurer Charles Théveneau de Morande, whose hatred, Brissot asserted, 'was the torment of my life'.

[80] In 1968 historian Robert Darnton affirmed some of these accounts,[81] and reaffirmed them in the 1980s, holding Brissot up as a case-study in the understanding of the difficult circumstances many philosophes encountered attempting to support themselves by their writing.

[82] Brissot's life and thinking are so well documented, from his early age through to his execution, many historians have examined him as a representative figure displaying the Enlightenment attitudes that drove many of the leading French revolutionaries.

Darnton sees him in this way, but also argued that he was intimately tangled in the business of "Grub Street", the scrappy world of publishing for profit in the eighteenth century, which was essential to the spread of Enlightenment ideas.

Historian Frederick Luna has argued that the letters and memoirs from which Darnton drew his information were written fifteen years after his supposed employment and that the timeline does not work out because Brissot was documented as having left Paris as soon as he was released from the Bastille (where he was held on suspicion of writing libelles) and therefore could not have talked with the police as alleged.

Brissot's idea of a fair, democratic society, with universal suffrage, living in moral as well as political freedom, foreshadowed many modern liberationist ideologies.

He was a strong disciple of Sextus Empiricus and applied those theories to modern science at the time in order to make knowledge well known about the enlightenment of Ethos.

"[6] Brissot's stance on the King's execution and the war with Austria, and his moderate views on the Revolution intensified the friction between the Girondins and Montagnards, who allied themselves with disaffected sans-culottes.

[88] Historian and political theorist Peter Kropotkin suggested that Brissot represented the "defenders of property" and the "states-men", which would become the Girondins, also known as the "War Party.

"[89] They were known for this name because they clamoured for a war that would ultimately force the king to step down (as opposed to a popular revolution); Brissot is quoted as saying, "We want some great treachery.

"[90] His opinion, recorded in his pamphlet "A sel commettants" ("To Salt Principals"), was that the masses had no "managing capacity" and that he feared a society ruled by "the great unwashed.

I can prove to-day: first, that this party of anarchists has dominated and still dominates nearly all the deliberations of the Convention and the workings of the Executive Council; secondly, that this party has been and still is the sole cause of all the evils, internal as well as the external, which afflict France; and thirdly, that the Republic can only be saved by taking rigorous measures to wrest the representatives of the nation from the despotism of this faction... Laws that are not carried into effect, authorities without force and despised, crime unpunished, property attacked, the safety of the individual violated, the morality of the people corrupted, no constitution, no government, no justice, these are the features of anarchy!

"[92] The Girondins, or Brissotins as they were initially called, were a group of loosely affiliated individuals, many of whom came from Gironde, rather than an organized party, but the main ideological emphasis was on preventing revolution and protecting private property.