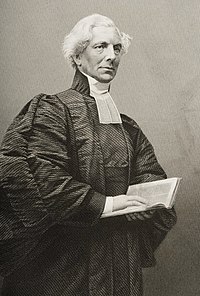

James Braid (surgeon)

He held that whoever talked of a "universal remedy" was either a fool or a knave: similar diseases often arose from opposite pathological conditions, and the treatment ought to be varied accordingly.

At first a sceptic, holding that the whole of the so-called magnetic phenomena were the results of illusion, delusion, or excited imagination, he found in 1841 that one, at least, of the characteristic symptoms could not be accounted for in this manner: viz., the fact that many of the mesmerized individuals are quite unable to open their eyes.

Braid was much puzzled by this discovery, until he found that the "magnetic trance" could be induced, with many of its marvellous symptoms of catalepsy, aphasia, exaltation and depression of the sensory functions, by merely concentrating the patient’s attention on one object or one idea, and preventing all interruption or distraction whatever.

But in the state thus produced, none of the so-called higher phenomena of the mesmerists, such as the reading of sealed and hidden letters, the contents of which were unknown to the mesmerised person, could ever be brought about.

The final article's last paragraph read: And, along with the strong impression made upon Braid by the Medical Gazette's article, there was also the more recent impressions made by Thomas Wakley's exposure of the comprehensive fraud of John Elliotson's subjects, the Okey sisters,[23] Braid always maintained that he had gone to Lafontaine's demonstration as an open-minded sceptic, eager to examine the presented evidence at first hand – that is, rather than "entirely [depending] on reading or hearsay evidence for his knowledge of it"[24] – and, then, from that evidence, form a considered opinion of Lafontaine's work.

He was neither a closed-minded cynic intent on destroying Lafontaine, nor a deluded and naïvely credulous believer seeking authorization of his already formed belief.

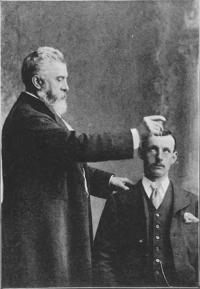

[33] The exceptional success of Braid's use of 'self-' or 'auto-hypnotism' (rather than 'hetero-hypnotism'), entirely by himself, on himself, and within his own home, clearly demonstrated that it had nothing whatsoever to do with the 'gaze', 'charisma', or 'magnetism' of the operator; all it needed was a subject's 'fixity of vision' on an 'object of concentration' at such a height and such a distance from the bridge of their nose that the desired 'upwards and inwards squint' was achieved.

[34] Braid conducted a number of experiments with self-hypnotization upon himself, and, by now convinced that he had discovered the natural psycho-physiological mechanism underlying these quite genuine effects, he performed his first act of hetero-hypnotization at his own residence, before several witnesses, including Captain Thomas Brown (1785–1862) on Monday 22 November 1841 – his first hypnotic subject was Mr. J.

The following Saturday, (27 November 1841) Braid delivered his first public lecture at the Manchester Athenæum, in which, amongst other things, he was able to demonstrate that he could replicate the effects produced by Lafontaine, without the need for any sort of physical contact between the operator and the subject.

[35] On the evening of Sunday, 10 April 1842, at St Jude's Church, Liverpool, the controversial cleric Hugh Boyd M'Neile preached a sermon against Mesmerism for more than ninety minutes to a capacity congregation;[36] and, according to most critics, it was a poorly argued and unimpressive performance.

[41] He then moved into a confusing admixture of philippic (against Braid and Lafontaine), and polemic (against animal magnetism), wherein he concluded that all mesmeric phenomena were due to "satanic agency".

Soon after, he also wrote a report entitled "Practical Essay on the Curative Agency of Neuro-Hypnotism", which he applied to have read before the British Association for the Advancement of Science in June 1842.

[56] as a means of engaging a natural physiological mechanism that was already hard-wired into each human being: In 1843, he published Neurypnology; or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep Considered in Relation with Animal Magnetism..., his first and only book-length exposition of his views.

The most efficient way to produce it was through visual fixation on a small bright object held eighteen inches above and in front of the eyes.

[citation needed] He completely rejected Franz Mesmer's idea that a magnetic fluid caused hypnotic phenomena, because anyone could produce them in "himself by attending strictly to the simple rules" that he had laid down.

The (derogative) proposal that Braidism be adopted as a synonym for "hypnotism" was rejected by Braid;[59] and it was rarely used at the time of that proposition,[60] and is never used today.

According to the extensive press reports, "the interest felt by the members of the institution in the subject was manifested by the attendance of one of the largest audiences we ever recollect to have seen present".

These … should be placed in a prominent position in every hypnotic laboratory: (1) The hyperæsthesia of the organs of special sense, which enabled im- pressions to be perceived through the ordinary media that would have passed unrecognised in the waking condition.

[64] (6) The vivid state of the imagination in hypnosis, which instantly invest- ed every suggested idea, or remembrance of past impressions, with the attributes of present realities.

(8) The tendency of the human mind, in those with a great love of the mar- vellous, erroneously to interpret the subject's replies in accordance with their own desires.

)[65] In his presentation Braid stressed that, because he had clearly demonstrated that the effects of hypnotism were "quite reconcilable with well-established physiological and psychological principles" (viz., they were well connected to the prevailing canonical knowledge), it was highly significant that none of the extraordinary effects that the mesmerists and animal magnetists routinely claimed for their operations – such as clairvoyance, direct mental suggestion, and mesmeric intuition – could be produced with hypnotism.

So, he argued, it was clear that their claims were entirely without foundation.However, he also stressed to his audience that, whilst it was, indeed, entirely true that these effects could not be produced with hypnotism – and whilst the claims of the mesmerists and animal magnetists were, ipso facto, entirely false – one must not make the mistake of concluding that this was unequivocal evidence of deception, dishonesty, or outright fraud on the part of those making these erroneous claims.In Braid’s view (given that many of the proponents of such views were decent men, and that their experiences had been honestly recounted), the only possible explanation was that their observations were seriously flawed.To Braid, these faults in their investigatory processes were "the chief source of error".

He urged the audience – before any of the claims of the mesmerists and animal magnetists could be examined in any way, or any of their findings investigated, or any confidence be placed in any of the recorded results of any of their experiments – that the entire process of the research that they had conducted, the investigative procedures that they had employed, and the experimental design that had underpinned their enterprise must be closely examined for the presence of what he termed "sources of fallacy".In the process of delivering his lecture, Braid spoke in some detail of six "sources of fallacy" that could contaminate findings.

[68] On 12 March 1852, convinced (as both a scientist and physiologist) of the genuineness of Braid's hypnotism,[69] Braid's friend and colleague William Benjamin Carpenter presented a significant paper, "On the influence of Suggestion in Modifying and directing Muscular Movement, independently of Volition", to the Royal Institution of Great Britain (it was published later that year).

My theory, moreover, has this additional recommendation, that it is level to our comprehension, and adequate to account for all which is demonstrably true, without offering any violence to reason and common sense, or being at variance with generally admitted physiological and psychological principles.

[72] At the conclusion of his paper, Carpenter briefly noted that his proposed ideo-motor principle of action, specifically created to explain Braid's hypnotism, could also explain other activities involving objectively psychosomatic responses, such as the movements of divining rods: Braid immediately adopted Carpenter's ideo-motor terminology.

However, by 1855, based on suggestions that had been made to Carpenter by their friend in common, Daniel Noble — that Carpenter's innovation would be more accurately understood, and more accurately applied (viz., not just limited to divining rods and pendulums), if it were designated the "ideo-dynamic principle"[73] — Braid was referring to a "mono-ideo-dynamic principle of action": Braid maintained an active interest in hypnotism until his death.

[77] Braid's work had a strong influence on a number of important French medical figures, especially Étienne Eugène Azam (1822–1899) of Bordeaux (Braid's principal French "disciple"), the anatomist Pierre Paul Broca (1824–1880),[78] the physiologist Joseph Pierre Durand de Gros (1826–1901) [fr],[79] and the eminent hypnotherapist, and co-founder of the Nancy School, Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault (1823–1904).

[88] In 1896, Bramwell noted that, "[Braid's name] is familiar to all students of hypnotism and is rarely mentioned by them without due credit being given to the important part he played in rescuing that science from ignorance and superstition".

[Braid] considered that the mental phenomena were only rendered possible by previous physical changes; and, as the result of these, the operator was enabled to act like an engineer, and to direct the forces which existed in the subject's own person.

as discussed in his Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind

(Yeates, 2005, p.119).

Neurypnology (1843), pp. 12–13.