Jansenism

Augustinus provoked lively debates, particularly in France, where five propositions, including the doctrines of limited atonement and irresistible grace, were extracted from the work and declared heretical by theologians hostile to Jansen.

Taking a broader view, the estimation of Marie-José Michel is that the Jansenists occupied an empty space between the ultramontane project of Rome and the construction of Bourbon absolutism.French Jansenism is a creation of Ancien Régime society [...].

[8]: 453 Therefore Jansenism cannot be wholly encapsulated as a fixed theological doctrine defended by easily identifiable supporters claiming a system of thought, but rather, it represented the variable and diverse developments of part of French and European Roman Catholicism in the early modern period.

In the 5th century, the North African bishop Augustine of Hippo opposed the British monk Pelagius who maintained that man has, within himself, the strength to will the good and to practice virtue, and thus to carry out salvation; a position that reduces the importance of divine grace.

[6]: 9 In the wake of Renaissance humanism, certain Roman Catholics had a less pessimistic vision of man and sought to establish his place in the process of salvation by relying on Thomistic theology, which appeared to be a reasonable compromise between grace and free will.

[6]: 108 It is in this context that Aquinas was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in 1567.Nevertheless, theological conflict increased from 1567, and in Leuven, the theologian Michel de Bay (Baius) was condemned by Pope Pius V for his denial of the reality of free will.

In response to Baius, the Spanish Jesuit Luis de Molina, then teaching at the University of Évora, defended the existence of 'sufficient' grace, which provides man with the means of salvation, but only enters into him by the assent of his free will.

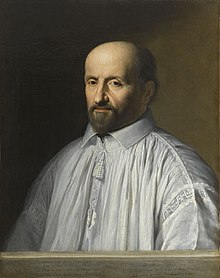

The book consisted of three volumes: In the first decade of the 17th century, Jansen established a fruitful collaboration with one of his classmates at the University of Leuven, the Baianist Jean du Vergier de Hauranne, later the abbot of Saint-Cyran-en-Brenne.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the principal religious movement was the French school of spirituality, mainly represented by the Oratory of Jesus founded in 1611 by Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle, a close friend of Vergier.

In opposition to Vergier, Richelieu in his book Instruction du chrétien ('Instruction of the Christian', 1619), along with the Jesuits, supported the thesis of attrition (imperfect contrition) that is, for them, the "regret for sins based solely on the fear of hell" is sufficient for one to receive the sacraments.

In this letter, the prelates denounced the five propositions as "composed in ambiguous terms, which could only produce heated arguments",[21] and requested the pope to be careful not to condemn Augustinianism too hastily, which they considered to be the official doctrine of the Church on the question of grace.

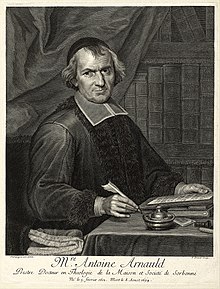

[20]: 85 At the same time, Antoine Arnaud openly doubted the presence of the five propositions in the work of Jansen, introducing the suspicion of manipulation on the part of the opponents of the Jansenists.The prelates also asked Innocent X to appoint a commission similar to the Congregatio de Auxiliis to resolve the situation.

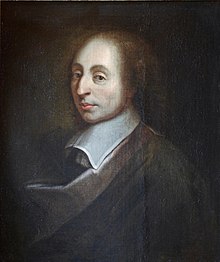

[22] Seventeen other Provinciales followed, and on 24 March 1657, Pascal made a contribution to a work entitled Écrits des curés de Paris ("Writings of Parisian priests"),[20]: 106 in which the moral laxity of the Jesuits was condemned.

According to Gazier, the main reason for this prohibition was not the theology (which was 'unassailable'), nor even the attacks against the Jesuits, but rather the fact that religious debates were raised in public, "the doctrinal part of the Provinciales is unassailable; they could not be censored by the Sorbonne or condemned by the popes, and if they were put in the Index, like the Discourse on the Method [of René Descartes], it was because they were disapproved of for having treated, in French, for the people of the world and for women, contentious questions of which only scholars should have been aware.

At the urging of several bishops, and at the personal insistence of King Louis XIV, Pope Alexander VII sent to France the apostolic constitution Regiminis Apostolici in 1664, which required, according to the Enchiridion symbolorum, "all ecclesiastical personnel and teachers" to subscribe to an included formulary, the Formula of Submission for the Jansenists.[25]: n.

Following this measure, the main Jansenist theologians went into exile: Pierre Nicole settled in Spanish Flanders until 1683, Antoine Arnauld took refuge in Brussels in 1680 and was joined by Jacques Joseph Duguet [fr] in 1685, an Augustinian Oratorian.

A provincial conference, consisting of forty theology professors from the Sorbonne, headed by Noël Alexandre, declared that the cleric should receive absolution.The publication of this 'Case of Conscience' provoked outrage among the anti-Jansenist elements in the Roman Catholic Church.

The bull saw in the propositions listed a summary of Jansenism, but, in addition to questions relating to the problem of grace, traditional positions on Gallicanism and the theology of Edmond Richer are condemned, which brought even more theologians to oppose the Jansenists, who in turn felt threatened.

The new archbishop Charles-Gaspard-Guillaume de Vintimille du Luc banished nearly three hundred Jansenist priests from his diocese, and closed the main sanctuaries of the movement, the Saint-Magloire seminary, the College of Sainte Barbe and the House of Sainte-Agathe, all three in Paris.

Initially a series of miracles linked to the tomb of the Jansenist deacon François de Pâris in the Saint-Médard Cemetery in Paris, including religious ecstasy, the phenomenon transformed into an expression of opposition to papal and royal authority.

Strayer related a case of torture documented in 1757 where a woman was "beat [...] with garden spades, iron chains, hammers, and brooms [...] jabbed [...] with swords, pelted [...] with stones, buried [...] alive, [...] crucified."

[43] "Let the Constituent Assembly, once it has emerged from the stormy discussions that mark its beginning and the votes of its major state laws, address the civil constitution of the clergy; Jansenist inspiration will preside over the organisation of the new Church.

[47] At the beginning of the 20th century, historians such as Louis Madelin and Albert Mathiez refuted this Jansenist conspiracy thesis and emphasised a conjunction of forces and demands as responsible for both the outbreak of the Revolution and the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

Burdened with years, glory and infirmities, he was forced to seek in Holland shelter from their vexations; he soon died in Amsterdam amid feelings of piety and resignation, after having spent his life defending the discipline and customs of the Early Church, of which he was the most zealous.

Relations between Utrecht and French Jansenism had developed early on, since vicar apostolic Johannes van Neercassel, friend of Antoine Arnauld and Pasquier Quesnel,[48]: 651–652 and in 1673 published an 'uncompromisingly Jansenist work', Amor Poenitens, which was frequently criticised by the Jesuits.

[48]: 652 His successor, Petrus Codde, who was influenced by Arnauld and Quesnel, and did much to promote Jansenism in the Dutch Mission including harbouring French Jansenist refugees, was suspended by Clement XI in 1702, despite his popularity with the local population.

[3]: 56–58 In Lombardy, a territory administered directly by Vienna, the theologians Pietro Tamburini, professor of the seminary at Brescia then at the University of Pavia, and Giuseppe Zola propagated the theology of Richer which was deeply imbued with Jansenism.

After the disappearance of the Annales de la religion in 1803, Henri Grégoire and a few survivors of the Constitutional Church including Claude Debertier [fr] published between 1818 and 1821 the Chronique religieuse ('Religious chronicle'), described by Augustin Gazier as a 'combat magazine'.

1) the scant real value of a book in which the author poses as a man of the world and a philosopher to judge the actions, doctrines and feelings of men who are essentially and above all Christians; 2) the extent and difficulty of the work to be done to identify all the errors and blunders into which Mr. Sainte-Beuve must necessarily have fallen by placing himself in the point of view he has chosen.

This was how a certain number of politicians of the Bourbon Restoration, the July Monarchy or the French Third Republic were frequently associated with Jansenism, such as Pierre Paul Royer-Collard, Victor Cousin or Jules Armand Dufaure.