Japanese sword

Kissaki usually have a curved profile, and smooth three-dimensional curvature across their surface towards the edge—though they are bounded by a straight line called the yokote and have crisp definition at all their edges.

Fake signatures ("gimei") are common not only due to centuries of forgeries but potentially misleading ones that acknowledge prominent smiths and guilds, and those commissioned to a separate signer.

In modern times the most commonly known type of Japanese sword is the Shinogi-Zukuri katana, which is a single-edged and usually curved sabre traditionally worn by samurai from the 15th century onwards.

Many examples can be seen at an annual competition hosted by the All Japan Swordsmith Association,[28] under the auspices of the Nihontō Bunka Shinkō Kyōkai (Society for the Promotion of Japanese Sword Culture).

The Bizen school had enjoyed the highest prosperity for a long time, but declined rapidly due to a great flood which occurred in the late 16th century during the Sengoku period.

Archaeological excavations of the Ōshū Tohoku region show iron ore smelting sites dating back to the early Nara period.

"Warabitetō " gained its fame through the series of battles between Emishi people (蝦夷) and the Yamato-chotei government (大 和朝廷) in the late eighth century.

According to the Nihonto Meikan, the Ōshū swordsmith group consists of the Mokusa (舞草), the Gassan (月山) and the Tamatsukuri (玉造), later to become the Hoju (寶壽) schools.

This was the standard form of carrying the sword for centuries, and would eventually be displaced by the katana style where the blade was worn thrust through the belt, edge up.

At the end of the Kamakura period, simplified hyogo gusari tachi came to be made as an offering to the kami of Shinto shrines and fell out of use as weapons.

The swordsmiths of the Sōshū school represented by Masamune studied tachi that were broken or bent in battle, developed new production methods, and created innovative Japanese swords.

Furthermore, in the late 16th century, tanegashima (muskets) were introduced from Portugal, and Japanese swordsmiths mass-produced improved products, with ashigaru fighting with leased guns.

[56] In later Japanese feudal history, during the Sengoku and Edo periods, certain high-ranking warriors of what became the ruling class would wear their sword tachi-style (edge-downward), rather than with the scabbard thrust through the belt with the edge upward.

They were both swordsmiths and metalsmiths, and were famous for carving the blade, making metal accouterments such as tsuba (handguard), remodeling from tachi to katana (suriage), and inscriptions inlaid with gold.

The craft of making swords was kept alive through the efforts of some individuals, notably Miyamoto kanenori (宮本包則, 1830–1926) and Gassan Sadakazu (月山貞一, 1836–1918), who were appointed Imperial Household Artist.

Under the United States occupation at the end of World War II all armed forces in occupied Japan were disbanded and production of Japanese swords with edges was banned except under police or government permit.

[30][31] In Japan, genuine edged hand-made Japanese swords, whether antique or modern, are classified as art objects (and not weapons) and must have accompanying certification to be legally owned.

In this period, it was believed that swords were multifunctional; in spirit they represent proof of military accomplishment, in practice they are coveted weapons of war and diplomatic gifts.

[110] The Meiji period (1868–1912) saw the dissolution of the samurai class, after foreign powers demanded Japan open their borders to international trade – 300-hundred years of Japanese isolation came to an end.

Swords were no longer necessary, in war or lifestyle, and those who practiced martial arts became the "modern samurai" – young children were still groomed to serve the emperor and put loyalty and honour above all else, as this new era of rapid development required loyal, hard working men.

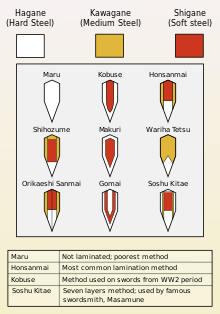

During this process the billet of steel is heated and hammered, split and folded back upon itself many times and re-welded to create a complex structure of many thousands of layers.

This process takes place in a darkened smithy, traditionally at night, so that the smith can judge by eye the colour and therefore the temperature of the sword as it is repeatedly passed through the glowing charcoal.

In the different schools of swordmakers there are many subtle variations in the materials used in the various processes and techniques outlined above, specifically in the form of clay applied to the blade prior to the yaki-ire, but all follow the same general procedures.

The precise way in which the clay is applied, and partially scraped off at the edge, is a determining factor in the formation of the shape and features of the crystalline structure known as the hamon.

Some other marks on the blade are aesthetic: dedications written in Kanji characters as well as engravings called horimono depicting gods, dragons, or other acceptable beings.

In some instances, an "umbrella block", positioning the blade overhead, diagonally (point towards the ground, pommel towards the sky), would create an effective shield against a descending strike.

The style most commonly seen in "samurai" movies is called buke-zukuri, with the katana (and wakizashi, if also present) carried edge up, with the sheath thrust through the obi (sash).

For a long time, Japanese people have developed a unique appreciation method in which the blade is regarded as the core of their aesthetic evaluation rather than the sword mountings decorated with luxurious lacquer or metal works.

In these books, the three swordsmiths treated specially in "Kyōhō Meibutsu Chō" and Muramasa, who was famous at that time for forging swords with high cutting ability, were not mentioned.

The reasons for this are considered to be that Yamada was afraid of challenging the authority of the shogun, that he could not use the precious sword possessed by the daimyo in the examination, and that he was considerate of the legend of Muramasa's curse.