A Dictionary of the English Language

In 1746, a consortium of London's most successful printers, including Robert Dodsley and Thomas Longman – none could afford to undertake it alone – set out to satisfy and capitalise on this need by the ever-increasing reading and writing public.

But perhaps the greatest single fault of these early lexicographers was, as historian Henry Hitchings put it, that they "failed to give sufficient sense of [the English] language as it appeared in use.

By 1747 Johnson had written his Plan of a Dictionary of the English Language, which spelled out his intentions and proposed methodology for preparing his document.

He clearly saw benefit in drawing from previous efforts, and saw the process as a parallel to legal precedent (possibly influenced by Cowell): I shall therefore, since the rules of stile, like those of law, arise from precedents often repeated, collect the testimonies of both sides, and endeavour to discover and promulgate the decrees of custom, who has so long possessed whether by right or by usurpation, the sovereignty of words.Johnson's Plan received the patronage of Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield but not to Johnson's pleasure.

[8] Seven years after first meeting Johnson to discuss the work, Chesterfield wrote two anonymous essays in The World that recommended the Dictionary.

[8] He complained that the English language was lacking structure and argued: We must have recourse to the old Roman expedient in times of confusion, and chose a dictator.

[9]However, Johnson did not appreciate the tone of the essay, and he felt that Chesterfield had not made good on his promise to be the work's patron.

[9] In a letter, Johnson explained his feelings about the matter: Seven years, my lord, have now past since I waited in your outward rooms or was repulsed from your door, during which time I have been pushing on my work through difficulties of which it is useless to complain, and have brought it at last to the verge of publication without one act of assistance, one word of encouragement, or one smile of favour.

Among the best-known are: A couple of less well-known examples are: He included whimsical little-known words, such as: On a more serious level, Johnson's work showed a heretofore unseen meticulousness.

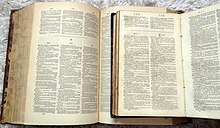

Unlike all the proto-dictionaries that had come before, painstaking care went into the completeness when it came not only to "illustrations" but also to definitions as well: The original goal was to publish the dictionary in two folio volumes: A–K and L–Z.

Subsequent printings ran to four volumes; even these formed a stack 10 inches (25 cm) tall, and weighed in at nearly 21 pounds (9.5 kg).

[citation needed] In addition to the sheer physical heft of Johnson's dictionary, came the equally hefty price: £4/10/– (equivalent to approximately £883 in 2025).

[citation needed] Johnson's etymologies would be considered poor by modern standards, and he gave little guide to pronunciation; one example being "Cough: A convulsion of the lungs, vellicated by some sharp serosity.

From the beginning there was universal appreciation not only of the content of the Dictionary but also of Johnson's achievement in single-handedly creating it: "When Boswell came to this part of Johnson's life, more than three decades later, he pronounced that 'the world contemplated with wonder so stupendous a work achieved by one man, while other countries had thought such undertakings fit only for whole academies'.

[24] Despite the Dictionary's critical acclaim, Johnson's general financial situation continued in its dismal fashion for some years after 1755: "The image of Johnson racing to write Rasselas to pay for his mother's funeral, romantic hyperbole though it is, conveys the precariousness of his existence, almost four years after his work on the Dictionary was done.

In July 1762 Johnson was granted a state pension of £300 a year by the twenty-four-year-old monarch, George III.

"[25] As lexicography developed, faults were found with Johnson's work: "From an early stage there were noisy detractors.

"[26] "Horace Walpole summed up for the unbelievers when he pronounced at the end of the eighteenth century, 'I cannot imagine that Dr Johnson's reputation will be very lasting.'

Notwithstanding Walpole's reservations, the admirers out-numbered the detractors, and the reputation of the Dictionary was repeatedly boosted by other philologists, lexicographers, educationalists and word detectives.

His Classical leanings led him to prefer spellings that pointed to Latin or Greek sources, "while his lack of sound scholarship prevented him from detecting their frequent errors".

Other than stress indication, the dictionary did not feature many word-specific orthoepical guidelines, with Johnson stating that 'For pronunciation, the best general rule is, to consider those as the most elegant speakers who deviate least from the written sounds' and referring to the irregular pronunciations as 'jargon'; this was subject to coetaneous criticism by John Walker, who wrote in the preface of his Critical Pronouncing Dictionary 'It is certain, where custom is equal, this ought to take place; and if the whole body of respectable English speakers were equally divided in thir pronunciation of the word busy, one half pronuncing it bew-ze, and the other half biz-ze, that the former ought to be accounted the most elegant speakers; but till this is the case, the latter pronunciation, though a gross deviation from orthography, will be esteemed the most elegant.

"[33] "In his history of the Oxford English Dictionary, Simon Winchester asserts of its eighteenth-century predecessor that 'by the end of the century every educated household had, or had access to, the great book.

'"[34] One of the first editors of the OED, James Murray, acknowledged that many of Johnson's explanations were adopted without change, for 'When his definitions are correct, and his arrangement judicious, it seems to be expedient to follow him.'

"[35] Johnson's influence was not confined to Britain and English: "The president of the Florentine Accademia declared that the Dictionary would be 'a perpetual Monument of Fame to the Author, an Honour to his own Country in particular, and a general Benefit to the Republic of Letters'.

"[40] Notwithstanding the evolution of lexicography in America, "The Dictionary has also played its part in the law, especially in the United States.

Legislators are much occupied with ascertaining 'first meanings', with trying to secure the literal sense of their predecessors' legislation ... Often it is a matter of historicizing language: to understand a law, you need to understand what its terminology meant to its original architects ... as long as the American Constitution remains intact, Johnson's Dictionary will have a role to play in American law.

"Dr. Johnson's Great Dictionary" appears as a plot device in the 1944 Sherlock Holmes film, The Pearl of Death, starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce.

[49] At the end of Chapter 1 of Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray Becky Sharp disdainfully throws a copy of Johnson's Dictionary out the window.