Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton

[7] Research by Emerson Baker in 1989 uncovered over 70 extant deeds documenting private purchases of land from indigenous peoples by English-speaking settlers, the earliest dating to 1639.

[17] In light of the Eisenhower administration's Indian termination policy, counsel opined that "obtaining a fair hearing of their claim would be virtually impossible.

[20] The Passamaquoddy representatives were kept waiting for 5 hours after their scheduled meeting time with the governor, and the attorney general "smiled and wished them well if they ever took their claim to court.

"[21] Soon after the meeting, pursuant to a vote of the Passamaquoddy tribal council, 75 members protested against the construction project along Route 1, resulting in 10 arrests.

[35] Although Tureen's team had come up with alternate theories to overcome Maine's sovereign immunity, the well-pleaded complaint rule, and delay-based defenses, it was "clearly established" that none of those weaknesses would apply to a Nonintercourse Act suit by the federal government.

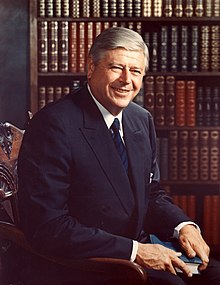

[35] On mid-May, Tureen persuaded Governor Kenneth Curtis to issue a public statement saying that the Passamaquoddy deserved their date in court.

[40] The tribes asked for a declaratory judgment and a preliminary injunction requiring the Interior Department to file suit for $25 billion in damages and 12.5 acres (51,000 m2) of land.

[42] Further, proceedings in the district court were put on hold until the First Circuit dismissed the Secretary's interlocutory appeal from Judge Gignoux's preliminary order in 1973.

[56] After Judge Gignoux's decision became final, the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot gained federal recognition in 1976, thus becoming eligible for $5 million/year in housing, education, health care, and other social services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

[59] With no one to negotiate with, Tureen devoted his energy to assisting the Solicitors Office in researching the legal and historical basis of the claim.

[60] In September 1976, Boston law firm Ropes & Gray opined that the state's $27 million municipal bond issue could not go forward using property within the claim area as collateral.

[61] On September 29, Governor Longley flew to Washington, and Maine's delegation introduced legislation directing the federal courts not to hear the tribe's claim; Congress adjourned before the bills could be considered.

[63] Patterson evaluated various other options, and recommended a land and cash settlement; however, in December 1976, Ford decided to pass this issue to the next administration: that of President Jimmy Carter.

[65] Interior's memo reached Peter Taft—the grandson of President Taft, and the head of the Justice Department's Land and Natural Resources Division—who wrote to Judge Gignoux, declaring his intention to litigate test cases concerning 5,000,000–8,000,000 acres (20,000–32,000 km2) of forests (mostly owned by large forestry companies) within the claim area on June 1, unless a settlement was reached.

[69] Carter named retiring judge William B. Gunter, of the state Supreme Court of Georgia, to mediate the dispute.

[73] On July 15, 1977, in a four-page memorandum to President Carter, Gunter announced his proposed solution: $25 million from the federal treasury, 100,000 acres (400 km2) from the disputed area to be assembled by the state and conveyed to the federal government in trust (20% of the state's holdings within the claim area), and the option to purchase 400,000 acres (1,600 km2) at fair market value as negotiated by the Interior Secretary.

[76] In October 1977, Carter appointed a new three-member task force (the "White House Work Group"), consisting of Eliot Cutler, a former legislative assistant to Senator Muskie and staffer at OMB, Leo M. Krulitz, the Interior Solicitor, and A. Stevens Clay, a partner at Judge Gunter's law firm.

[77] Over a period of months, the task force facilitated negotiations over a settlement that would include portions of cash, land, and BIA services.

[79] The memorandum called for 300,000 acres (1,200 km2), with the additional land coming from the paper and timber companies, and a $25 million trust fund for the tribes.

[82] In response, in June, Attorney General Griffin Bell threatened to commence the first phase of the litigation against the state for 350,000 acres (1,400 km2) and $300 million.

[85] Although the tribes made progress in implementing the Hathaway plans with the paper and timber companies, Krulitz ceased to support the proposal when the full extent of the required federal appropriations became clear.

[86] Krulitz was replaced with Eric Jankel—assistant for intergovernmental affairs to Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus—with whom Tureen had previously negotiated the settlement to the Narragansett land claim in Rhode Island.

[87] Tureen and Jankel—along with Donald Perkins, a lawyer for the paper and timber companies—negotiated a solution whereby $30 million of the settlement funds would come from various programs in the federal budget.

[89] Third, in Wilson v. Omaha Indian Tribe (1979), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the provision of the Nonintercourse Act placing the burden of proof in land claims on non-Indians did not apply to U.S. state defendants (but did apply to corporate defendants); further, language in Wilson threatened to confine the applicability of the Act to Indian country.

[97] Second, Governor Brennan's choice to replace Muskie (and thus inherit his predecessor's committee assignments) was George Mitchell (D-ME)—who had supported the land claim as U.S. Attorney and possessed legal gravitas due to his tenure as a District Judge.

"[105] MICSA provided that the "Passamaquoddy Tribe, the Penobscot Nation, and their members, and the land and natural resources owned by, or held in trust [for them] .

In an opinion striking all the defendants' affirmative defenses against the Narragansett land claim, the Rhode Island district court noted that "[our] task has been greatly simplified by the First Circuit's analysis of the [Nonintercourse] Act in" Passamaquoddy.

Paterson and David Roseman—who, as Deputy and Assistant Attorneys General for the State of Maine, respectively, were involved in the litigation—published a law review article criticizing the First Circuit's Passamaquoddy decision.

[123] According to Paterson and Roseman, "[n]either the district nor circuit courts in Passamaquoddy v. Morton had all the available legislative history, administrative rulings, legal analysis or case law necessary to make a fully informed decision.

"[127] But, in Kempers' view, "[i]n the final analysis, however, the settlement negotiations appear to have compromised the very basis of the claim" by bringing the tribes under "much closer state supervision.