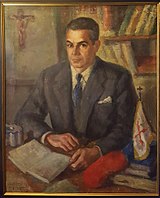

José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino

[13] José and María settled in Santander and had 6 children;[14] they were brought up "en un hogar español cristiano y montañes", learning "to prey to God and to love Spain"[15] and with a sense of local Cantabrian pride.

[30] The best-known relative of José Luis is his older cousin, Marcial Solana González-Camino; an Integrist Cortes deputy in 1916, he made his name in the 1920s and 1930s as Traditionalist philosopher and author.

[37] During the run-up to the 1933 elections it seemed that Nicolás would emerge at the forefront,[38] but in unclear circumstances it turned out that José Luis represented the Carlists on the joint Santander list of Unión de Derechas Agrarias.

[59] Politically Zamanillo remained among the Carlist hawks; though he signed the Bloque Nacional funding act,[60] in 1935 he developed enmity towards the monarchist alliance advanced by the likes of Rodezno and Pradera.

[62] The policy backfired when in 1936 the Carlists were left out of the local Cantabrian Candidatura Contrarrevolucionaria;[63] standing on their own[64] they fared badly and Zamanillo lost his Cortes ticket with just 12,000 votes gathered.

[73] He was among key architects[74] of a so-called "Plan de los Tres Frentes",[75] a project of toppling the Republic by means of an exclusively Carlist coup;[76] it crashed in early June when security unearthed a depot with hundreds of false Guardia Civil uniforms.

[103] Having hardly noticed the ascent of Franco he rather saluted Don Javier as a new caudillo[104] and had problems[105] coming to terms with the vision of perhaps necessary,[106] transitional military dictatorship before a Traditionalist monarchy gets reinstated.

[109] Informal talks with the military produced an idea of organizing systematic training for Carlist would-be officers,[110] the concept which materialized as Real Academia Militar de Requetés, announced by Fal to be set up shortly.

Already in early January 1937 he met Dávila in vain seeking to ensure Fal's return,[115] yet at the time the lot of Jefe Delegado was getting gradually eclipsed by rumors of amalgamating Carlism into sort of a new state party.

[117] During the following session, held in March in Burgos, he and Valiente acted as chief Falcondistas and displayed most skepticism about would-be unification, confirming that attacks against Comunión hierarchy were unacceptable;[118] nevertheless, the junta vaguely and unanimously agreed that political unity was a must.

[119] The same month he denounced political maneuvering[120] and presented the military with Don Javier's letter advocating the return of Fal;[121] though Zamanillo remained on amicable terms with Mola,[122] he was viewed increasingly unfavorably in Franco's entourage.

[124] In the aftermath of Unification Decree, on April 19 enraged Zamanillo resigned from all functions;[125] he was so disgusted with apparent bewilderment among the Carlist executive that he concluded that Fal's exile worked to his advantage, allowing Jefe Delegado to maintain an honorable position.

[139] He made sure that Comunión remained neutral towards the European war,[140] that claims of the new Alfonsist claimant Don Juan were rejected[141] with pro-Juanista sympathies eradicated[142] and that there was no political collaboration with the regime.

In 1943 he co-signed Reclamacion del poder, Carlist memorandum demanding introduction of Traditionalist monarchy;[146] in May he was detained,[147] spent a week in police dungeons[148] and was ordered exile in Albacete,[149] terminated in April 1944.

[154] He used to attend the gathering systematically, present also in 1947,[155] though in the late 1940s his relations with Sivatte, chief personality of Catalan Carlism, deteriorated; Zamanillo's calls for discipline were largely aimed against the Sivattistas.

[156] Confirmed as member of Consejo Nacional[157] and attending the first gathering or regional leaders since Insua he was bent on preserving Traditionalist identity against Francoist distortions and called for setting up Centro de Estudios Doctrinales.

[158] An awkward sign of recognition came in wake of his 1948 trip to Rome,[159] when the émigré PSUC periodical noted him among "dirigents del [Carlist] movimient" whose dissidence demonstrated ongoing decomposition of Francoism.

[163] Most likely he kept practicing as a lawyer, as demonstrated by proceedings related both to minors and to politics: in 1953 he was involved in machinations to ensure that former wife of another Carlist claimant, the late Carlos VIII, would not get legal custody of their juvenile daughters.

On the Carlist front he remained loyal to Fal and kept fighting the increasingly vocal Sivattistas;[165] none of the sources consulted clarifies whether he joined those pressing Don Javier to terminate the regency and to claim monarchic rights himself, what sort of happened in Barcelona in 1952;[166] it was only much later that he declared it a grave error.

Don Javier did not nominate a new Jefe Delegado, creating a new collegial executive, Secretaría Nacional; according to some scholars Zamanillo initially was not appointed[170] and got recommended by Fal slightly afterwards,[171] according to others he formed part from the onset.

Within Carlism the anti-Francoist feelings were running high,[174] with especially the Navarros and the Gipuzkoanos trying to sabotage his nomination;[175] during the 1956 Montejurra gathering they tried to block his access to the microphone, and when he finally succeeded, they cut the cables.

Unlike the older generation, for whom Zamanillo was an icon of requeté, Carlos Hugo and his aides, like Ramón Massó and José María Zavala, were far more skeptical.

[247] Hugocarlista strategy worked perfectly; disguising their progressive agenda they deflected the conflict from ideological confrontation to secondary issues, isolated their opponent,[248] provoked him into unguarded moves, and removed the key person[249] bent on preventing their intended control of Carlism.

[252] In 1962 Franco thought him a candidate for vice-minister of justice, nomination thwarted by Carrero Blanco, who denounced him – either erroneously or as part of own stratagem – as supporter of Carlos Hugo.

[269] On the other hand, he supported the 1966 introduction of Tercio Familiar as a step towards Traditionalist type of representation;[270] claiming that backbone of Traditionalism was doctrinal rather than dynastical[271] in 1969 he voted in favor of Juan Carlos as the future king.

[275] He kept leading Hermandad of ex-combatants, periodically purging it of the most vocal Javieristas;[276] at the turn of the decades he considered it a would-be platform to launch a new Carlist organization, a "Comunión without a king".

[287] Following the so-called Ley Arias of December 1974, which legalized political associations, he first tried to mobilize support by means of a new periodical, Brújula,[288] gathering together "partidarios de la Monarquía tradicional, social y representativa".

[289] In June[290] 1975 the initiative materialized with 25,000 signatures required[291] as Unión Nacional Española; Zamanillo entered its Comisión Permanente[292] and in early 1976 jointly with Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora[293] its presidency,[294] becoming also member of Junta Directiva.

[295] The association, in 1976 officially registered as political party, adhered to Traditionalist principles;[296] Zamanillo explained its objectives as "lo que hay que hacer es un 18 de julio pacífico y político",[297] played down differences with other right-wing groupings[298] and advanced suggestions of a National Front,[299] formed by UNE, ANEPA, UDPE and others.

[300] In May 1976 he co-organized Traditionalist attempt to dominate the annual Carlist Montejurra gathering, since mid-1960s controlled by the Hugocarlistas; the day produced violence, with two Partido Carlista militants shot.