Joule expansion

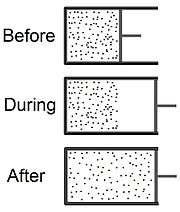

The Joule expansion (a subset of free expansion) is an irreversible process in thermodynamics in which a volume of gas is kept in one side of a thermally isolated container (via a small partition), with the other side of the container being evacuated.

The Joule expansion, treated as a thought experiment involving ideal gases, is a useful exercise in classical thermodynamics.

An actual Joule expansion experiment necessarily involves real gases; the temperature change in such a process provides a measure of intermolecular forces.

, confined to one half of a thermally isolated container (see the top part of the drawing at the beginning of this article).

A thermometer inserted into the compartment on the left (not shown in the drawing) measures the temperature of the gas before and after the expansion.

When the molecular motion is random, temperature is the measure of the internal kinetic energy.

If the chambers have not reached equilibrium, there will be some kinetic energy of flow, which is not detectable by a thermometer (and therefore is not a component of heat).

[4] In practice, the simple two-chamber free expansion experiment often incorporates a 'porous plug' through which the expanding air must flow to reach the lower pressure chamber.

The purpose of this plug is to inhibit directional flow, thereby quickening the reestablishment of thermal equilibrium.

Since the total internal energy does not change, the stagnation of flow in the receiving chamber converts kinetic energy of flow back into random motion (heat) so that the temperature climbs to its predicted value.

If the initial air temperature is low enough that non-ideal gas properties cause condensation, some internal energy is converted into latent heat (an offsetting change in potential energy) in the liquid products.

Thus, at low temperatures the Joule expansion process provides information on intermolecular forces.

Unlike ideal gases, the temperature of a real gas will change during a Joule expansion.

As a result, expanding a gas usually increases the potential energy associated with intermolecular forces.

[7][8] When molecules are close together, however, repulsive interactions are much more important and it is thus possible to get an increase in temperature during a Joule expansion.

[9] It is theoretically predicted that, at sufficiently high temperature, all gases will warm during a Joule expansion[5] The reason is that at any moment, a very small number of molecules will be undergoing collisions; for those few molecules, repulsive forces will dominate and the potential energy will be positive.

If the temperature is high enough, that can make the total potential energy positive, in spite of the much larger number of molecules experiencing weak attractive interactions.

For an ideal gas, the change in entropy[10] is the same as for isothermal expansion where all heat is converted to work:

For an ideal monatomic gas, the entropy as a function of the internal energy U, volume V, and number of moles n is given by the Sackur–Tetrode equation:[11]

For a monatomic ideal gas U = 3/2nRT = nCVT, with CV the molar heat capacity at constant volume.

In some books one demands that a quasistatic route has to be reversible, here we don't add this extra condition.

For the above defined path we have that dU = 0 and thus T dS = P dV, and hence the increase in entropy for the Joule expansion is

A third way to compute the entropy change involves a route consisting of reversible adiabatic expansion followed by heating.

We first let the system undergo a reversible adiabatic expansion in which the volume is doubled.

During the expansion, the system performs work and the gas temperature goes down, so we have to supply heat to the system equal to the work performed to bring it to the same final state as in case of Joule expansion.

Heating the gas up to the initial temperature Ti increases the entropy by the amount

We might ask what the work would be if, once the Joule expansion has occurred, the gas is put back into the left-hand side by compressing it.

Joule performed his experiment with air at room temperature which was expanded from a pressure of about 22 bar.

Rather, one can calculate that the temperature of the air should drop by about 3 degrees Celsius when the volume is doubled under adiabatic conditions.

[12] However, due to the low heat capacity of the air and the high heat capacity of the strong copper containers and the water of the calorimeter, the observed temperature drop is much smaller, so Joule found that the temperature change was zero within his measuring accuracy.